Natural logarithm

[1] The natural logarithm of x is generally written as ln x, loge x, or sometimes, if the base e is implicit, simply log x.

[2][3] Parentheses are sometimes added for clarity, giving ln(x), loge(x), or log(x).

Logarithms are useful for solving equations in which the unknown appears as the exponent of some other quantity.

They are important in many branches of mathematics and scientific disciplines, and are used to solve problems involving compound interest.

[6] Their work involved quadrature of the hyperbola with equation xy = 1, by determination of the area of hyperbolic sectors.

An early mention of the natural logarithm was by Nicholas Mercator in his work Logarithmotechnia, published in 1668,[7] although the mathematics teacher John Speidell had already compiled a table of what in fact were effectively natural logarithms in 1619.

[8] It has been said that Speidell's logarithms were to the base e, but this is not entirely true due to complications with the values being expressed as integers.

This usage is common in mathematics, along with some scientific contexts as well as in many programming languages.

[nb 1] In some other contexts such as chemistry, however, log x can be used to denote the common (base 10) logarithm.

Generally, the notation for the logarithm to base b of a number x is shown as logb x.

The natural logarithm of a positive, real number a may be defined as the area under the graph of the hyperbola with equation y = 1/x between x = 1 and x = a.

Area does not change under this transformation, but the region between a and ab is reconfigured.

How to establish this derivative of the natural logarithm depends on how it is defined firsthand.

then the derivative immediately follows from the first part of the fundamental theorem of calculus.

On the other hand, if the natural logarithm is defined as the inverse of the (natural) exponential function, then the derivative (for x > 0) can be found by using the properties of the logarithm and a definition of the exponential function.

to show that the harmonic series equals the natural logarithm of

Nowadays, more formally, one can prove that the harmonic series truncated at N is close to the logarithm of N, when N is large, with the difference converging to the Euler–Mascheroni constant.

The natural logarithm allows simple integration of functions of the form

In other words, when integrating over an interval of the real line that does not include

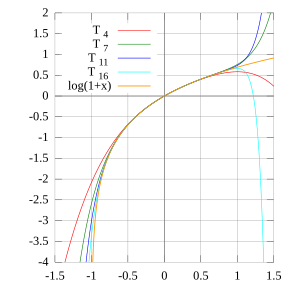

where x > 1, the closer the value of x is to 1, the faster the rate of convergence of its Taylor series centered at 1.

Such techniques were used before calculators, by referring to numerical tables and performing manipulations such as those above.

The natural logarithm of 10, approximately equal to 2.30258509,[13] plays a role for example in the computation of natural logarithms of numbers represented in scientific notation, as a mantissa multiplied by a power of 10:

To compute the natural logarithm with many digits of precision, the Taylor series approach is not efficient since the convergence is slow.

Especially if x is near 1, a good alternative is to use Halley's method or Newton's method to invert the exponential function, because the series of the exponential function converges more quickly.

Another alternative for extremely high precision calculation is the formula[14][15]

In fact, if this method is used, Newton inversion of the natural logarithm may conversely be used to calculate the exponential function efficiently.

and π can be pre-computed to the desired precision using any of several known quickly converging series.)

[16] Based on a proposal by William Kahan and first implemented in the Hewlett-Packard HP-41C calculator in 1979 (referred to under "LN1" in the display, only), some calculators, operating systems (for example Berkeley UNIX 4.3BSD[17]), computer algebra systems and programming languages (for example C99[18]) provide a special natural logarithm plus 1 function, alternatively named LNP1,[19][20] or log1p[18] to give more accurate results for logarithms close to zero by passing arguments x, also close to zero, to a function log1p(x), which returns the value ln(1+x), instead of passing a value y close to 1 to a function returning ln(y).

This keeps the argument, the result, and intermediate steps all close to zero where they can be most accurately represented as floating-point numbers.

Similar inverse functions named "expm1",[18] "expm"[19][20] or "exp1m" exist as well, all with the meaning of expm1(x) = exp(x) − 1.