Classical conditioning

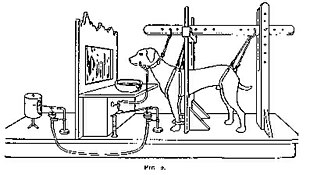

[1] The Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov studied classical conditioning with detailed experiments with dogs, and published the experimental results in 1897.

For example, it may affect the body's response to psychoactive drugs, the regulation of hunger, research on the neural basis of learning and memory, and in certain social phenomena such as the false consensus effect.

[9] The best-known and most thorough early work on classical conditioning was done by Ivan Pavlov, although Edwin Twitmyer published some related findings a year earlier.

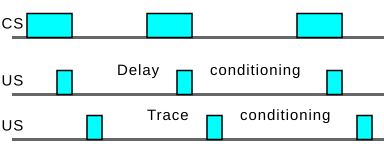

Pavlov reported many basic facts about conditioning; for example, he found that learning occurred most rapidly when the interval between the CS and the appearance of the US was relatively short.

The example below shows the temporal conditioning, as US such as food to a hungry mouse is simply delivered on a regular time schedule such as every thirty seconds.

The speed of conditioning depends on a number of factors, such as the nature and strength of both the CS and the US, previous experience and the animal's motivational state.

Then, in a series of trials, the rat is exposed to a CS, a light or a noise, followed by the US, a mild electric shock.

Tests of these predictions have led to a number of important new findings and a considerably increased understanding of conditioning.

Among these are two phenomena described earlier in this article Latent inhibition might happen because a subject stops focusing on a CS that is seen frequently before it is paired with a US.

In fact, changes in attention to the CS are at the heart of two prominent theories that try to cope with experimental results that give the R–W model difficulty.

[9] As stated earlier, a key idea in conditioning is that the CS signals or predicts the US (see "zero contingency procedure" above).

The role of such context is illustrated by the fact that the dogs in Pavlov's experiment would sometimes start salivating as they approached the experimental apparatus, before they saw or heard any CS.

[16] Such so-called "context" stimuli are always present, and their influence helps to account for some otherwise puzzling experimental findings.

The associative strength of context stimuli can be entered into the Rescorla-Wagner equation, and they play an important role in the comparator and computational theories outlined below.

Instead, the organism records the times of onset and offset of CSs and USs and uses these to calculate the probability that the US will follow the CS.

More flexibility is provided by assuming that a stimulus is internally represented by a collection of elements, each of which may change from one associative state to another.

These often include the assumption that associations involve a network of connections between "nodes" that represent stimuli, responses, and perhaps one or more "hidden" layers of intermediate interconnections.

Such models make contact with a current explosion of research on neural networks, artificial intelligence and machine learning.

It appears that other regions of the brain, including the hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex, contribute to the conditioning process, especially when the demands of the task get more complex.

"[29] Fear and eyeblink conditioning involve generally non overlapping neural circuitry, but share molecular mechanisms.

Fear conditioning occurs in the basolateral amygdala, which receives glutaminergic input directly from thalamic afferents, as well as indirectly from prefrontal projections.

[30] As NMDA receptors are only activated after an increase in presynaptic calcium(thereby releasing the Mg2+ block), they are a potential coincidence detector that could mediate spike timing dependent plasticity.

Systematic desensitization is a treatment for phobias in which the patient is trained to relax while being exposed to progressively more anxiety-provoking stimuli (e.g. angry words).

The nigrostriatal pathway, which includes the substantia nigra, the lateral hypothalamus, and the basal ganglia have been shown to be involved in hunger motivation.

[citation needed] The influence of classical conditioning can be seen in emotional responses such as phobia, disgust, nausea, anger, and sexual arousal.

A common example is conditioned nausea, in which the CS is the sight or smell of a particular food that in the past has resulted in an unconditioned stomach upset.

As an adaptive mechanism, emotional conditioning helps shield an individual from harm or prepare it for important biological events such as sexual activity.

For example, sexual arousal has been conditioned in human subjects by pairing a stimulus like a picture of a jar of pennies with views of an erotic film clip.

Similar experiments involving blue gourami fish and domesticated quail have shown that such conditioning can increase the number of offspring.

These results suggest that conditioning techniques might help to increase fertility rates in infertile individuals and endangered species.