Postage stamps and postal history of the Confederate States

The postage stamps and postal system of the Confederate States of America carried the mail of the Confederacy for a brief period in U.S. history.

Early in 1861 when South Carolina no longer considered itself part of the Union and demanded that the U.S. Army abandon Fort Sumter, plans for a Confederate postal system were already underway.

It was not until June 1 that the Confederate Post Office took over collection and delivery, now faced with the task of providing postage stamps and mail services for its citizens.

President Jefferson Davis had appointed John Henninger Reagan on March 6, 1861, to head the new Confederate Post Office Department.

Because Confederate post offices existed for only a few years and official and informal records of them are lacking, relatively little is known about their operations in many regions of the South.

Existing data has been studied by several experts in the field, who have reconstructed an account of their existence and operation largely from surviving Confederate covers (stamped-addressed envelopes), and by researchers specializing in advanced studies of Confederate philately, notably Colonel Harvey E. Sheppard, United States Army, Fort Hood, Texas; the late Van Dyk MacBride, Newark, New Jersey; George N. Malpass, St. Petersburg, Florida; Earl Antrim, Nampa, Idaho; David Kohn, Washington, D. C., and a few others, each contributing material in the concerted effort to create an overall account of Confederate postal history.

Upon appointment Reagan became a close friend of Davis and was Postmaster General for the duration of the war, making him the only PMG of the short-lived Confederacy.

These took a variety of forms, from envelopes prestamped with a postmark modified to say "paid" or an amount, to regular stamps produced by local printers.

[7] Within a month after his appointment as Postmaster General, Reagan ordered that ads be placed in both Southern and Northern newspapers seeking sealed proposals from printing companies for producing Confederate postage stamps.

The Confederate Post Office Department therefore awarded the contract to lithographers Hoyer & Ludwig, a small firm in Richmond.

The first Confederate postage issues were placed in circulation in October 1861, five months after postal service between the North and South had ended.

During the five months between the U.S. Post office's withdrawal of services from the seceded states and the first issue of Confederate postage stamps, postmasters throughout the Confederacy used temporary substitutes for postal payment.

During this brief span, the Confederate Post Office contracted with five different printing companies to produce postage stamps: Archer & Daly of Richmond, Virginia; Hoyer & Ludwig of Richmond, Virginia; J. T. Paterson & Co. of Augusta, Georgia; Thomas de la Rue & Co., Ltd., of London, England; and Keatinge & Ball of Columbia, South Carolina.

The first Confederate Postage stamps were issued and placed in circulation on October 16, 1861, five months after postal service between the North and South had been suspended.

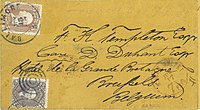

A considerable number of Confederate covers (i.e. stamped - addressed envelope) survived the Civil War and through the many years since they were mailed and have been avidly sought after and preserved by historians and collectors alike.

The war had divided family members and friends across the country, and letter writing naturally increased dramatically, especially to and from the men who were away serving in an army.

Although contemporary official records are often fragmentary or missing, and many details remain unclear, the covers with their addresses, dated postmarks, special markings and the letters themselves have provided much insight for historians and collectors in their studies of Civil War postal history.

[15] Many collectors over the years have marked or destroyed fakes and forgeries upon identification in an effort to keep the collecting pool safe from such material.

Once at the exchange point, the outer envelope was removed and discarded while the inner cover containing the prisoner's letter was examined by military officials and delivered.

For a time a prisoner and mail exchange program was in use that lasted until June 1863, when the U.S. government terminated any further cooperation due to mounting war tensions and increased mistrust.

The Union blockade reduced a vital source of revenue for the south, cotton exports, to a fraction of what they were prior to the war, as well as preventing much of its mail from being sent or received.

[24] In response to the blockade various specially-built steamers were built and put to use by British investors who were heavily invested in the cotton and tobacco trade.

These vessels were typically smaller and lighter in weight, often giving them an advantage of maneuverability and record speeds of up to 17 knots, which enabled them to evade or outrun Union ships on patrol.

[23] During the beginning of the Civil War, getting Confederate mail in and out of the Confederacy to and from foreign suppliers and other interested parties overseas posed a problem.

Consequently, inbound covers that were prepared by forwarding agents for transfer to and delivery within the Confederacy never received various postmarks or other markings from the Confederate post office.

Confederate blockade covers are highly sought after by collectors and historians who often regard these mailings as figurative time-stamps and historical confirmation that various people, ships and post offices existed in and among these times and places.

Because the lower Mississippi River was being blockaded effectively dividing the Western Confederate states from those east, New Orleans became one of the busiest of ports.

Citizens, many of whom had family members and friends off fighting in the war, or who had died in battle, often expressed their loyalties with envelopes illustrated with flags, portraits, slogans and allegorical figures such as that of Liberty, which clearly captured the sentiments of that time.

This practice was most evident in the North where there were many printers, especially in the larger cities, who produced an assortment of envelopes that proudly displayed these designs and which quickly became popular among the citizenry.

The South also lacked the North's industrialized advantages and supplies, and so the various Confederate patriotic covers that have survived the years are scarce and rare and usually have considerable value.

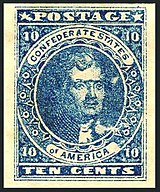

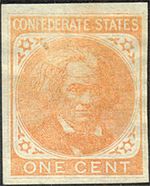

1861 issue

1862 reissue

1862 reissue

1862 issue

issue of 1862, typograph

1862 typograph

1863 issue

The franking privilege (free postage) for various C.S.A. government officials officially ended in March 1861 except for the Postmaster General and other members of his department. Other government agencies were required to prepay postage, even the secretary of war during wartime, as evidenced on this cover.

May 24, 1864, St. George's, Bermuda to Wilmington by blockade-runner Lynx

Various departments of the Confederate government used envelopes which were printed with the names of their department. Examples where the words 'Official Business' are used are common, but these envelopes were not official in any way, and required payment of postage, unlike official envelopes of the US government whose postage is free, referred to as the free franking privilege .

The CSA ended franking privileges on March 15, 1861, but the CSA Post Office made provision that allowed the postmaster general and other officials in the CSA Post Office to send official mail free of charge when endorsed "Official Business" over their signatures.

March 18, 1863

Confederate 10-cent Thomas Jefferson. Postmark, Richmond, Virginia, November 11, 1861, circular date stamp on eleven-star flag patriotic envelope to Oxford, Georgia .