Conspiracies in ancient Egypt

Texts are generally silent on the subject of struggles for influence, but a few historical sources, either indirect or very eloquent, depict a royal family disunited and agitated by petty grudges.

He appears to be Prince Zannanza, mentioned in Hittite writings such as the Gesture of Shouppilouliouma and Moursili's Prayer to All the Gods, both of which refer to diplomatic letters exchanged between Emperor Šuppiluliuma and an anonymous Egyptian queen, Akhenaten's widow.

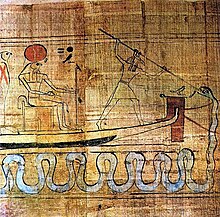

Having secretly measured the exact length of Osiris' body, Typhon had a superb and remarkably ornate chest built, and ordered it to be brought to a feast.

At the same moment, all the guests rushed to close the lid (...) Once the operation was completed, the chest was carried up the river and lowered into the sea.As we know from The Adventures of Horus and Set,[n 1] after the disappearance of Osiris, the main problem was not so much to punish the murderer as to find the best candidate for the Pharaonic office.

In all three cases, it is disturbing to note that the plotters perpetrated their murderous deeds at a time when the Pharaoh's sacred aura had been exhausted (around the age of thirty), just before the celebration of the Sed-Festival, which was supposed to regenerate the sovereign and restore his physical and divine vigour.

For example, Pharaoh Ay (sixty at investiture), successor to Tutankhamun (twenty at death), performed the ritual and social role of a son even though he was biologically old enough to be a grandfather.

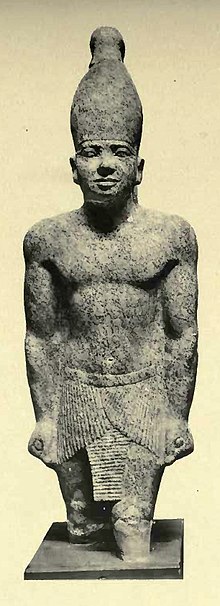

According to the Ptolemaic historian Manetho of Sebennytos (2nd century BC), Pharaoh Teti reigned for thirty years, then perished through the deception of his bodyguards:[39] The sixth dynasty consisted of six kings from Memphis.1.

Othoes for thirty years: he was assassinated by his bodyguards.According to Egyptologist Naguib Kanawati, who carried out the archaeological excavation of Teti's burial complex, some disturbing facts suggest that this pharaoh's life was effectively ended by a conspiracy.

For some, the decoration of the tombs remains unfinished, for others only the name has been erased, and for still others their wall representations have been carefully hammered out – either entirely, or in part (head and/or feet).

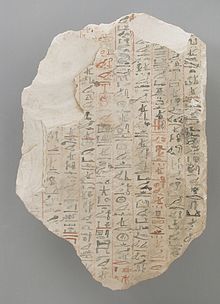

The biography of the high dignitary Ouni, inscribed in his Abydaean mastaba, mentions that a secret trial was held within the harem to judge the misdeeds of a royal wife.

The historian Manetho of Sebennytos gives a very fanciful description of this ruler: "A certain Nitokris reigned, the most energetic of men and the most beautiful of women of her time, blonde with rosy cheeks.

[59] His natural successor and coregent, Prince Senusret, was absent from the palace, busy waging war in the Libyan desert, no doubt to commit razzias to finance the lavish expenses of the royal jubilee.

Under these conditions, and with the usual reservations, it's tempting to link this Qakarê king to the troubles reported in Upper Egypt by certain inscriptions at El-Tod and Elephantine at the beginning of Senusret's reign.

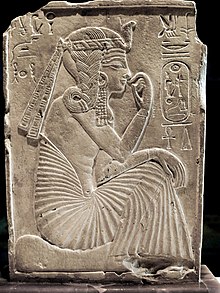

The eldest daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, she rose to the rank of Great Royal Wife after the death of her mother in the sixteenth year of her father's reign.

While the Hittite prince Zannanza was on his way to Egypt, priests in Merytaten's entourage drew up an official title for this future king: "Ânkhéperourê Smenkhkarê".

[92] In 1977, thanks to new excavations, William Murname concluded that the Karnak fresco represented not a fallen prince, but the soldier Mehy, a commoner whose family origins are unknown.

To date, however, it has not been established that Mehy was ever elevated to the rank of royal heir, a position successively occupied by the commoners Ay, Horemheb and Ramesses I before their enthronement.

Indeed, throughout his reign, Ramesses II never ceased to proclaim his right to the throne, no doubt to dissuade a member of the powerful military caste, Mehy or otherwise, from taking his place.

No crime will be imputed to him (follows the reciprocity clause on the Hittite side, using exactly the same terms).Between the death of Merneptah, son of Ramesses II, and the end of the 19th dynasty, there was a troubled period of some fifteen years.

It is disturbing to note that at the very moment when Seti granted this privilege to his wife (end of year 2), the usurper Amenmesse appeared on the scene as if the rise in power of the queen and her clan had shattered a fragile family equilibrium.

Labeled a "great enemy", i.e. a rebel and a schemer, Bay was killed without it being known whether he had been executed after a proper trial or assassinated in a plot hatched by the queen and her supporters.

[112][113] After the physical elimination of Chancellor Bay, Queen Twosret used every means at her disposal to impose her authority, even though the young Siptah remained Pharaoh.

It's hard to believe, however, that all the grandsons and great-grandsons of Ramesses II who were still alive at the time could have accepted without protest the accession to the supreme power of a brand-new royal family – parvenus, in short.

[118] The most likely hypothesis is that the pharaoh Twosret had lost the reins of power after coming into conflict with the clan descended from prince Khaemweset, the vizier Hori having lent his support to Sethnakht.

A small, flat Oudjat or "Eye of Horus" amulet, made of semi-precious stone and about 15 mm in diameter, was inserted by the embalmers into the lower right edge of the wound to guarantee the deceased protection and good health.

On the passive side, the controllers Patchaouemdiimen, Karpous, Khâmopet, Khâemmal, and the cupbearer Sethyemperdjehouty, the scribe Pairy and the harem lieutenant Imenkhâou were convicted of non-indictment.

In the trial documents, such as the Judicial Papyrus of Turin, they are changed into names of infamy which, while retaining their consonance, invert their meaning, thus pronouncing a veritable curse.

The Judicial Papyrus of Turin mentions the names of Parêkamenef, magician, Messoui and Shâdmesdjer, scribes of the house of life, as well as Iyry, director of the pure priests of Sekhmet.

Magical recipes were smuggled out of the royal library, soporific potions were concocted and wax figurines were fashioned to bewitch the palace guards: He began to make magical writings to disorganize and throw into confusion, making some wax gods and some philtres to render human limbs powerless, and handing them over to Pebekkamen(...) and the other great enemies with these words, "Bring them in," and, sure enough, they brought them in.

It was made up of two treasury chiefs, Montouemtaouy and Payefraouy, a senior courtier, the flabellum bearer Kar, five cupbearers, Paybaset, Qédenden, Baâlmaher, Pairousounou and Djéhoutyrekhnéfer, the royal herald Penrennout, two scribes from the dispatch office, Mây and Parâemheb, and the army standard-bearer Hori.