Constellation program

[5] Constellation began in response to the goals laid out in the Vision for Space Exploration under NASA Administrator Sean O'Keefe and President George W.

"[3] Work began on this revised Constellation Program, to send astronauts first to the International Space Station, then to the Moon, and then to Mars and beyond.

Despite the cancellation of the Constellation program, development of the Orion spacecraft continues, with a test launch performed on December 5, 2014.

Alternately, there was a small possibility that the original plan of using LOX/CH4–fueled engines on board the Block II (lunar) Orion CSM and Altair ascent stage would have been adopted.

The Orion spacecraft would have been launched into a low Earth orbit by the Ares I rocket (the "Stick"), developed by Alliant Techsystems, Rocketdyne, and Boeing.

[21][22][23] Formerly referred to as the Crew Launch Vehicle (CLV), the Ares I consisted of a single Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) derived in part from the primary boosters used in the Space Shuttle system, connected at its upper end by an interstage support assembly to a new liquid-fueled second stage powered by a J-2X rocket engine.

[24] NASA began developing the Ares I low Earth orbit launch vehicle (analogous to Apollo's Saturn IB), returning to a development philosophy used for the original Saturn I, test-launching one stage at a time, which George Mueller had firmly opposed and abandoned in favor of "all-up" testing for the Saturn V. As of May 2010, the program got as far as launching the first Ares I-X first-stage flight on October 28, 2009 and testing the Orion launch abort system before its cancellation.

NASA planned to use the first vehicles developed in the Constellation Program for Earth-orbit tasks formerly undertaken by the Space Shuttle.

[29] The design of the launch vehicle taking Orion into orbit, the Ares I, employs many concepts from the Apollo program.

Like those of the Apollo Program, Constellation program missions would involve its main vehicle, the Orion spacecraft, flying missions in low Earth orbit to service the International Space Station, and in conjunction with the Altair and Earth Departure Stage vehicles, on crewed flights to the polar regions of the Moon.

After a two-day orbital chase, the Orion spacecraft, having jettisoned much of the initial stack during takeoff, would meet with the International Space Station.

The six-man crew (at a maximum) would then enter the station in order to perform numerous tasks and activities for the duration of their flight, usually lasting six months, but possibly shortened to four or lengthened to eight, depending upon NASA's goals for that particular mission.

Once the Orion reached a safe distance from the ISS, the Command Module (after having jettisoned the disposable service module) would re-enter in the same manner as all NASA spacecraft prior to the Shuttle, using the ablative heat shield to both deflect heat from the spacecraft and to slow it down from a speed of 17,500 mph (28,200 km/h) to 300 mph (480 km/h).

After the necessary preparations for lunar flight, the EDS would fire for 390 seconds in a translunar injection (TLI) maneuver, accelerating the spacecraft to 25,000 miles per hour (40,200 km/h).

During the three-day trans-lunar coast, the four-man crew would monitor the Orion's systems, inspect their Altair spacecraft and its support equipment, and correct their flight path as necessary to allow the Altair to land at a near-polar landing site suitable for a future lunar base.

Upon receiving clearance from Mission Control, the Altair would undock from the Orion and perform an inspection maneuver, allowing ground controllers to inspect the spacecraft via live TV mounted on Orion for any visible problems that would prevent landing (on Apollo this was done by the Command Module Pilot).

After a two-and-a-half-day coast, the crew would jettison the Service Module (allowing it to burn up in the atmosphere) and the CM would reenter the Earth's atmosphere using a special reentry trajectory designed to slow the vehicle from its speed of 25,000 miles per hour (40,200 km/h) to 300 miles per hour (480 km/h) and thus allow a Pacific Ocean splashdown.

In the next launch window, 26 months after the first, the crew would go to Mars in an interplanetary transfer vehicle with nuclear thermal rocket and propellant modules assembled in Earth orbit.

If we humans want to survive for hundreds of thousands or millions of years, we must ultimately populate other planets ... colonize the Solar System and one day go beyond."

A report published in June 2014 by the US National Academy of Sciences called for clear long-term space goals at NASA.

The report said that the agency's current course invited "failure, disillusionment, and [loss of] the longstanding international perception that human space-flight is something that the United States does best."

Several possible paths for reaching the planet by 2037 were explored in the report, which noted that returning to the Moon would offer "significant advantages" as an intermediate step in the process.

This proposal[40] was to be a way to "establish an extended human presence on the Moon" to "vastly reduce the costs of further space exploration."

According to Bush, experience gained could help "develop and test new approaches and technologies and systems"[40] to begin a "sustainable course of long-term exploration.

"[8][9][10][43] A review concluded that it would cost on the order of $150 billion for Constellation to reach its objective if adhering to the original schedule.

[44] Another review in 2009, ordered by President Obama, indicated that neither a return to the Moon nor a crewed flight to Mars was within NASA's current budget.

[46] After reviewing the report, and following congressional testimony,[47] the Obama administration decided to exclude Constellation from the 2011 United States federal budget.

At the conference, President Obama and top officials, as well as leaders in the field of spaceflight, discussed the future of U.S. efforts in human spaceflight and unveiled a plan for NASA that followed the Augustine Panel's "Flexible Path to Mars" option,[51] modifying President Obama's prior proposal to include the continuing development of the Orion capsule as an auxiliary system to the ISS and setting the year 2015 as the deadline for the design of a new Super Heavy Launch Vehicle.

Private spacecraft are also operating under the Commercial Resupply Services program bringing cargo to ISS.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

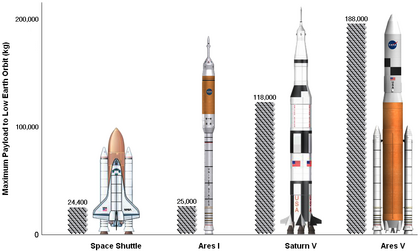

1. Space Shuttle payload includes crew and cargo. 2. Ares I payload includes only crew and inherent craft. 3. Saturn V payload includes crew, inherent craft and cargo. 4. Ares V payload includes only cargo and inherent craft.