Intuitionistic logic

From a proof-theoretic perspective, Heyting’s calculus is a restriction of classical logic in which the law of excluded middle and double negation elimination have been removed.

These, however, are technical means for studying Heyting’s deductive system rather than formalizations of Brouwer’s original informal semantic intuitions.

Semantical systems claiming to capture such intuitions, due to offering meaningful concepts of “constructive truth” (rather than merely validity or provability), are Kurt Gödel’s dialectica interpretation, Stephen Cole Kleene’s realizability, Yurii Medvedev’s logic of finite problems,[2] or Giorgi Japaridze’s computability logic.

Some authors have argued that this might be an indication of inadequacy of Heyting’s calculus itself, deeming the latter incomplete as a constructive logic.

[3] In the semantics of classical logic, propositional formulae are assigned truth values from the two-element set

In contrast, propositional formulae in intuitionistic logic are not assigned a definite truth value and are only considered "true" when we have direct evidence, hence proof.

A common objection to their use is the above-cited lack of two central rules of classical logic, the law of excluded middle and double negation elimination.

David Hilbert considered them to be so important to the practice of mathematics that he wrote: Taking the principle of excluded middle from the mathematician would be the same, say, as proscribing the telescope to the astronomer or to the boxer the use of his fists.

One reason for this is that its restrictions produce proofs that have the disjunction and existence properties, making it also suitable for other forms of mathematical constructivism.

One reason that this particular aspect of intuitionistic logic is so valuable is that it enables practitioners to utilize a wide range of computerized tools, known as proof assistants.

As such, the use of proof assistants (such as Agda or Coq) is enabling modern mathematicians and logicians to develop and prove extremely complex systems, beyond those that are feasible to create and check solely by hand.

The relation between them may always be used to obtain new formulas: A weakened premise makes for a strong implication, and vice versa.

Also all the principles in the next section involving quantifiers explain use of implications with hypothetical existence as premise.

Weakening statements by adding two negations before existential quantifiers (and atoms) is also the core step in the double-negation translation.

In contrast, in classical propositional logic it is possible to take one of those three connectives plus negation as primitive and define the other two in terms of it, in this way.

It is even possible to define all in terms of a sole sufficient operator such as the Peirce arrow (NOR) or Sheffer stroke (NAND).

These are fundamentally consequences of the law of bivalence, which makes all such connectives merely Boolean functions.

For simplicity of the discussion here and below, the formulas are generally presented in weakened forms without all possible insertions of double-negations in the antecedents.

and currying, the following generalization also entails the relation between implication and conjunction in the predicate calculus, discussed below.

For a variant of the De Morgan law concerning two existentially closed decidable predicates, see LLPO.

And both non-reversible theorems relating conjunction and implication mentioned in the introduction follow from this equivalence.

Now when using the principle in the next section, the following variant of the latter, with more negations on the left, also holds: A consequence is that Already minimal logic proves excluded middle equivalent to consequentia mirabilis, an instance of Peirce's law.

is always constructively valid, it follows that assuming double-negation elimination for all such disjunctions implies classical logic also.

For example, the disjunctive syllogism as presented generalizes to If some term exists at all, the antecedent here even implies

As shown by Alexander V. Kuznetsov, either of the following connectives – the first one ternary, the second one quinary – is by itself functionally complete: either one can serve the role of a sole sufficient operator for intuitionistic propositional logic, thus forming an analog of the Sheffer stroke from classical propositional logic:[6] The semantics are rather more complicated than for the classical case.

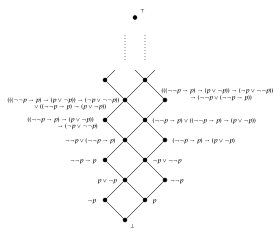

A formula is valid in intuitionistic logic if and only if it receives the value of the top element for any valuation on any Heyting algebra.

[8] Conversely, for every invalid formula, there is an assignment of values to the variables that yields a valuation that differs from the top element.

However, Robert Constable has shown that a weaker notion of completeness still holds for intuitionistic logic under a Tarski-like model.

The system of classical logic is obtained by adding any one of the following axioms: Various reformulations, or formulations as schemata in two variables (e.g. Peirce's law), also exist.

In general, one may take as the extra axiom any classical tautology that is not valid in the two-element Kripke frame