Corinna

[10] One of the first scholars to question this was Edgar Lobel,[11] who in 1930 concluded that there is no reason to believe she predated the orthography used on the Berlin papyrus, on which fragments of two of her poems are preserved.

[22] If the traditional date is correct, the lack of ancient reference to Corinna before the first century, and the later orthography, could both be explained by her being of only local interest before the Hellenistic period.

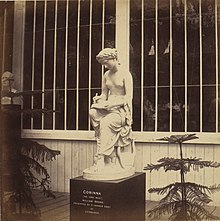

[23] An apparent terminus ante quem is established by the second-century AD theologian Tatian, who says in his Address to the Greeks that the fourth-century sculptor Silanion made a portrait-statue of Corinna.

[26] West, for instance, accepts that the Compiègne statuette is a copy of a fourth-century work, but suggests that it was not originally intended to depict Corinna, only gaining that association in the Roman period.

[20] Her works were collected in a Boeotian edition in the late third or early second century BC, and later Hellenistic and Roman texts of Corinna derived from this.

[48] According to a story recounted by Plutarch in On the Glory of the Athenians, she considered myth the proper subject for poetry, rebuking Pindar for not paying sufficient attention to it.

[49] Pindar was said to have responded to this criticism by filling his next ode with mythical allusions, leading Corinna to advise him, "Sow with the hand, not with the sack.

[60] She considers that although it was written by a woman, Corinna's poetry tells stories from a patriarchal point of view,[60] describing women's lives from a masculine perspective.

[63] Diane Rayor argues that although Corinna's poetry does not directly challenge patriarchal traditions, it is still "woman-identified", focusing on women's experiences and being written for a female audience.

[65] Skinner suggests that Corinna's songs were composed for performance by a chorus of young girls in religious festivals, and were related to the ancient genre of partheneia.

Possible settings include the Mouseia at Thespiae, proposed by West, and at the festival of the Daedala at Plataea, suggested by Gabriele Burzacchini.

[70] Alexander Polyhistor wrote a commentary on her work,[71] and she was named as a tenth canonical lyric poet in a scholion on Dionysius Thrax.

[73] In the nineteenth century, Corinna was still remembered as a poetic authority, Karl Otfried Müller presenting her as a preeminent ancient poet and citing the stories of her competition against Pindar.

[75] For instance, West describes Corinna as more gifted than most local poets, but lacking the originality that would put her on the same level as Bacchylides or Pindar.

[76] Athanassios Vergados argues that Corinna's poor reception among modern critics is due to her focus on local Boeotian traditions rather than broader subject matter, giving her a reputation of parochialism and thus limited quality.

[24] More recently, critics have begun to see Corinna's poetry as engaging with Panhellenic mythical and literary traditions, rewriting them to give Boeotian characters a more prominent role.