History of anthropometry

At various points in history, certain anthropometrics have been cited by advocates of discrimination and eugenics often as a part of some social movement or through pseudoscientific claims.

In 1716 Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton, who wrote many essays on comparative anatomy for the Académie française, published his Memoir on the Different Positions of the Occipital Foramen in Man and Animals (Mémoire sur les différences de la situation du grand trou occipital dans l'homme et dans les animaux).

Swedish professor of anatomy Anders Retzius (1796–1860) first used the cephalic index in physical anthropology to classify ancient human remains found in Europe.

He classed skulls in three main categories; "dolichocephalic" (from the Ancient Greek kephalê "head", and dolikhos "long and thin"), "brachycephalic" (short and broad) and "mesocephalic" (intermediate length and width).

[2] Charles Darwin, who thought the single-origin hypothesis essential to evolutionary theory, opposed Nott and Gliddon in his 1871 The Descent of Man, arguing for monogenism.

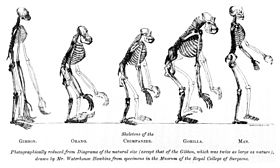

By comparing skeletons of apes to man, T. H. Huxley (1825–1895) backed up Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, first expressed in On the Origin of Species (1859).

Eugène Dubois' (1858–1940) discovery in 1891 in Indonesia of the "Java Man", the first specimen of Homo erectus to be discovered, demonstrated mankind's deep ancestry outside Europe.

Samuel George Morton (1799–1851) collected hundreds of human skulls from all over the world and started trying to find a way to classify them according to some logical criterion.

Cranioscopy was later renamed phrenology (phrenos: mind, logos: study) by his student Johann Spurzheim (1776–1832), who wrote extensively on "Drs.

A basically anthropometric division of body types into the categories endomorphic, ectomorphic and mesomorphic derived from Sheldon's somatotype theories is today popular among people doing weight training.

The "Bertillonage" system was based on the finding that several measures of physical features, such as the dimensions of bony structures in the body, remain fairly constant throughout adult life.

It was possible, by exhaustion, to sort the cards on which these details were recorded (together with a photograph) until a small number produced the measurements of the individual sought, independently of name.

England followed suit when in 1894, a committee sent to Paris to investigate the methods and its results reported favorably on the use of measurements for primary classification and recommended also the partial adoption of the system of finger prints suggested by Francis Galton, then in use in Bengal, where measurements were abandoned in 1897 after the fingerprint system was adopted throughout British India.

It was made famous by Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), the founder of anthropological criminology, who claimed to be able to scientifically identify links between the nature of a crime and the personality or physical appearance of the offender.

A few of the 14 identified traits of a criminal included large jaws, forward projection of jaw, low sloping forehead; high cheekbones, flattened or upturned nose; handle-shaped ears; hawk-like noses or fleshy lips; hard shifty eyes; scanty beard or baldness; insensitivity to pain; long arms, and so on.

During the 1920s and 1930s, though, members of the school of cultural anthropology of Franz Boas began to use anthropometric approaches to discredit the concept of fixed biological race.

Paul Kretschmer quoted an 1892 discussion with him concerning these criticisms, also citing Aurel von Törok's 1895 work, who basically proclaimed the failure of craniometry.

[17] Similar claims were previously made by Ho et al. (1980), who measured 1,261 brains at autopsy, and Beals et al. (1984), who measured approximately 20,000 skulls, finding the same East Asian → European → African pattern but warning against using the findings as indicative of racial traits, "If one merely lists such means by geographical region or race, causes of similarity by genogroup and ecotype are hopelessly confounded".

Z. Cernovsky Rushton's own study[21] shows that the average cranial capacity of North American blacks is similar to that of Caucasians from comparable climatic zones,[20] though a previous work by Rushton showed appreciable differences in cranial capacity between North Americans of different race.

Using this skull-based categorization, German philosopher Christoph Meiners in his The Outline of History of Mankind (1785) identified three racial groups: Ripley's The Races of Europe was rewritten in 1939 by Harvard physical anthropologist Carleton S. Coon.

Finally, he split "Australoid" from "Mongoloid" along a line roughly similar to the modern distinction between sinodonts in the north and sundadonts in the south.

[23] In The Races of Europe (1939) Coon classified Caucasoids into racial sub-groups named after regions or archaeological sites such as Brünn, Borreby, Alpine, Ladogan, East Baltic, Neo-Danubian, Lappish, Mediterranean, Atlanto-Mediterranean, Irano-Afghan, Nordic, Hallstatt, Keltic, Tronder, Dinaric, Noric and Armenoid.

Coon eventually resigned from the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, while some of his other works were discounted because he would not agree with the evidence brought forward by Franz Boas, Stephen Jay Gould, Richard Lewontin, Leonard Lieberman and others.

[30][obsolete source] Given three Americans who self-identify and are socially accepted as white, black and Hispanic, and given that they have precisely the same Afro-European mix of ancestries (one African great-grandparent), there is no objective test that will identify their group membership without an interview.