Critical mass

A numerical measure of a critical mass depends on the effective neutron multiplication factor k, the average number of neutrons released per fission event that go on to cause another fission event rather than being absorbed or leaving the material.

The mass where criticality occurs may be changed by modifying certain attributes such as fuel, shape, temperature, density and the installation of a neutron-reflective substance.

These examples only outline the simplest ideal cases: It is possible for a fuel assembly to be critical at near zero power.

If the perfect quantity of fuel were added to a slightly subcritical mass to create an "exactly critical mass", fission would be self-sustaining for only one neutron generation (fuel consumption then makes the assembly subcritical again).

Similarly, if the perfect quantity of fuel were added to a slightly subcritical mass, to create a barely supercritical mass, the temperature of the assembly would increase to an initial maximum (for example: 1 K above the ambient temperature) and then decrease back to the ambient temperature after a period of time, because fuel consumed during fission brings the assembly back to subcriticality once again.

Conversely changing the shape to a less perfect sphere will decrease its reactivity and make it subcritical.

Thermal expansion associated with temperature increase also contributes a negative coefficient of reactivity since fuel atoms are moving farther apart.

This reduces the number of neutrons which escape the fissile material, resulting in increased reactivity.

[2] Also, if the tamper is (e.g. depleted) uranium, it can fission due to the high energy neutrons generated by the primary explosion.

This can greatly increase yield, especially if even more neutrons are generated by fusing hydrogen isotopes, in a so-called boosted configuration.

If the size of the reactor core is less than a certain minimum, too many fission neutrons escape through its surface and the chain reaction is not sustained.

Most information on bare sphere masses is considered classified, since it is critical to nuclear weapons design, but some documents have been declassified.

Given a total interaction cross section σ (typically measured in barns), the mean free path of a prompt neutron is

Most interactions are scattering events, so that a given neutron obeys a random walk until it either escapes from the medium or causes a fission reaction.

So long as other loss mechanisms are not significant, then, the radius of a spherical critical mass is rather roughly given by the product of the mean free path

and the square root of one plus the number of scattering events per fission event (call this s), since the net distance travelled in a random walk is proportional to the square root of the number of steps: Note again, however, that this is only a rough estimate.

Several uncertainties contribute to the determination of a precise value for critical masses, including (1) detailed knowledge of fission cross sections, (2) calculation of geometric effects.

This latter problem provided significant motivation for the development of the Monte Carlo method in computational physics by Nicholas Metropolis and Stanislaw Ulam.

Finally, note that the calculation can also be performed by assuming a continuum approximation for the neutron transport.

However, as the typical linear dimensions are not significantly larger than the mean free path, such an approximation is only marginally applicable.

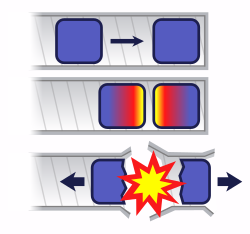

In the case of a uranium gun-type bomb, this can be achieved by keeping the fuel in a number of separate pieces, each below the critical size either because they are too small or unfavorably shaped.

In reality, this is impractical because even "weapons grade" 239Pu is contaminated with a small amount of 240Pu, which has a strong propensity toward spontaneous fission.

Because of this, a reasonably sized gun-type weapon would suffer nuclear reaction (predetonation) before the masses of plutonium would be in a position for a full-fledged explosion to occur.

This is fortunate for atomic power generation, for without this delay "going critical" would be an immediately catastrophic event, as it is in a nuclear bomb where upwards of 80 generations of chain reaction occur in less than a microsecond, far too fast for a human, or even a machine, to react.

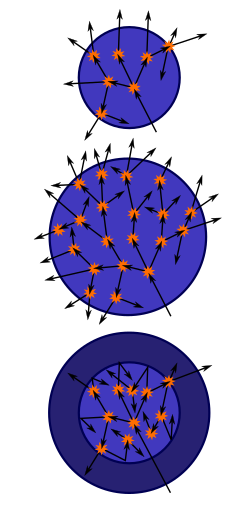

Middle: By increasing the mass of the sphere to a critical mass, the reaction can become self-sustaining.

Bottom: Surrounding the original sphere with a neutron reflector increases the efficiency of the reactions and also allows the reaction to become self-sustaining.