Nuclear chain reaction

The concept of a nuclear chain reaction was reportedly first hypothesized by Hungarian scientist Leó Szilárd on September 12, 1933.

[6] A few months later, Frédéric Joliot-Curie, H. Von Halban and L. Kowarski in Paris[7] [non-primary source needed]searched for, and discovered, neutron multiplication in uranium, proving that a nuclear chain reaction by this mechanism was indeed possible.

[8][additional citation(s) needed] In parallel, Szilárd and Enrico Fermi in New York made the same analysis.

[9] This discovery prompted the letter from Szilárd and signed by Albert Einstein to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning of the possibility that Nazi Germany might be attempting to build an atomic bomb.

Since nuclear chain reactions may only require natural materials (such as water and uranium, if the uranium has sufficient amounts of 235U), it was possible to have these chain reactions occur in the distant past when uranium-235 concentrations were higher than today, and where there was the right combination of materials within the Earth's crust.

Uranium-235 made up a larger share of uranium on Earth in the geological past because of the different half-lives of the isotopes 235U and 238U, the former decaying almost an order of magnitude faster than the latter.

Kuroda's prediction was verified with the discovery of evidence of natural self-sustaining nuclear chain reactions in the past at Oklo in Gabon in September 1972.

[12] To sustain a nuclear fission chain reaction at present isotope ratios in natural uranium on Earth would require the presence of a neutron moderator like heavy water or high purity carbon (e.g. graphite) in the absence of neutron poisons, which is even more unlikely to arise by natural geological processes than the conditions at Oklo some two billion years ago.

These free neutrons will then interact with the surrounding medium, and if more fissile fuel is present, some may be absorbed and cause more fissions.

Nuclear weapons, on the other hand, are specifically engineered to produce a reaction that is so fast and intense it cannot be controlled after it has started.

The fuel for energy purposes, such as in a nuclear fission reactor, is very different, usually consisting of a low-enriched oxide material (e.g. uranium dioxide, UO2).

[13] Because of the small amount of 235U that exists, it is considered a non-renewable energy source despite being found in rock formations around the world.

[14] Uranium-235 cannot be used as fuel in its base form for energy production; it must undergo a process known as refinement to produce the compound UO2.

Plutonium once occurred as a primordial element in Earth's crust, but only trace amounts remain so it is predominantly synthetic.

Another proposed fuel for nuclear reactors, which however plays no commercial role as of 2021, is uranium-233, which is "bred" by neutron capture and subsequent beta decays from natural thorium, which is almost 100% composed of the isotope thorium-232.

Also, several free neutrons, gamma rays, and neutrinos are emitted, and a large amount of energy is released.

When describing a nuclear reactor, where neutron population is directly proportional to thermal power, the following equation is used:

These factors, traditionally arranged chronologically with regards to the life of a neutron in a thermal reactor, include the probability of fast non-leakage

Both delayed neutrons and the transient fission product "burnable poisons" play an important role in the timing of these oscillations.

Beryllium-9, the only naturally-occurring stable isotope of beryllium, is capable of emitting a neutron when an alpha particle is absorbed.

[17] Without delayed neutrons, changes in reaction rates in nuclear systems would occur at speeds that are too fast for humans to control.

In these devices, the nuclear chain reaction begins after increasing the density of the fissile material with a conventional explosive.

Also, the geometry and density are expected to change during detonation since the remaining fission material is torn apart from the explosion.

Detonation of a nuclear weapon involves bringing fissile material into its optimal supercritical state very rapidly (about one microsecond, or one-millionth of a second).

Free neutrons, in particular from spontaneous fissions, can cause the device to undergo a preliminary chain reaction that destroys the fissile material before it is ready to produce a large explosion, which is known as predetonation.

For example, the Chernobyl disaster involved a runaway chain reaction, but the result was a low-powered steam explosion from the relatively small release of heat, as compared with a bomb.

[17] Such steam explosions would be typical of the very diffuse assembly of materials in a nuclear reactor, even under the worst conditions.

For example, power plants licensed in the United States require a negative void coefficient of reactivity (this means that if coolant is removed from the reactor core, the nuclear reaction will tend to shut down, not increase).

This eliminates the possibility of the type of accident that occurred at Chernobyl (which was caused by a positive void coefficient).

In such cases, residual decay heat from the core may cause high temperatures if there is loss of coolant flow, even a day after the chain reaction has been shut down (see SCRAM).

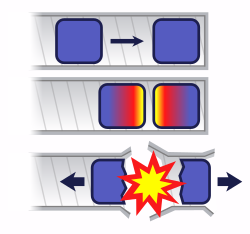

1) A uranium-235 atom absorbs a neutron and fissions into two fission fragments , releasing three new neutrons and a large amount of binding energy .

2) One of those neutrons is absorbed by an atom of uranium-238 , and does not continue the reaction. Another neutron leaves the system without being absorbed. However, one neutron does collide with an atom of uranium-235, which then fissions and releases two neutrons and more binding energy.

3) Both of those neutrons collide with uranium-235 atoms, each of which fissions and releases a few neutrons, which can then continue the reaction.