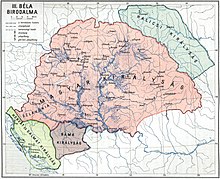

Croatia in personal union with Hungary

Later centuries were characterized by conflicts with the Mongols, who sacked Zagreb in 1242, competition with Venice for control over Dalmatian coastal cities, and internal warfare among Croatian nobility.

[16] In 1091 Ladislaus crossed the Drava river and conquered the entire province of Slavonia without encountering opposition, but his campaign was halted near the Iron Mountains (Mount Gvozd).

[13] Ladislaus appointed his nephew Prince Álmos to administer the controlled area of Croatia, established the Diocese of Zagreb as a symbol of his new authority and went back to Hungary.

[38] The alleged agreement called Pacta conventa (English: Agreed accords) or Qualiter (first word of the text) is today viewed as a 14th-century forgery by most modern Croatian historians.

[39] In the Kingdom of Croatia also existed own "consuetudines antiquae Croatorum", a customary law unique to the Croatian legal tradition compared to the Hungarian one ("consuetudo Hungaricalis").

[40][41][42] Presumably the earliest mention of the term "consuetudo Croatorum" is from 1348 when Ivan of Stipko of Bribir (i.e. Šubić) in his will left part of his estate to the Franciscan monastery of St. Mary in Bribir "despite the contrary Croatian custom, which forbids it" ("nec obstante consuetudine aliqua Chroatorum, qua prohibetur, ne quis suum Patrimonium aliis quam suis consaguineis vei propinquis alicui valeat dare").

[44] In 1376 gathered in Knin the "antiqui homines parcium Crohacie" (Croatian elders) to interpret the "iura Crohatorum" (Croat rights), and in the 15th century was legally used in the district of Šibenik ("Sesubiecerat iurisdictioni Sibenicensi cum hoc quod gubernaretur secundum leges Croatiae").

The term "Dalmatia" referred to several coastal cities and islands, at times used as a synonym of Croatia, and was to spread further inland only with the expansion of Venice in the 15th century.

[52] In 1116, after the death of Coloman, Venice attacked the Dalmatian coast, defeated the army of Croatian Ban Cledin and seized Biograd, Split, Trogir, Šibenik, Zadar and several islands.

King Stephen II, Coloman's successor, unsuccessfully tried to regain the lost cities in 1117, although the Doge of Venice Ordelafo Faliero was killed in a battle near Zadar.

[59] Most prominent Croatian noble families of the 12th and early 13th century were the Šubić (or Princes of Bribir), divided among various branches of the family and ruling over inland Dalmatia with their seat in Bribir; the Babonić in western Slavonia and along the right bank of the Kupa River; the Kačić between the Cetina and Neretva rivers with their seat in Omiš, known for practicing piracy; and the Frankopan (then known as the Princes of Krk), ruling over the island of Krk, Kvarner and the County of Modruš in northern Lika.

[66] In March 1242 the Mongols were near Split and started attacking Klis, since they thought King Béla, who was at the time in Trogir, was hiding there, but failed to capture its fortress.

One group returned east through Zeta, Serbia, and Bulgaria, all of which were looted as they passed through, while the second one plundered the area of Dubrovnik and burned the town of Kotor.

Since the Mongols still held much of Eastern Europe, work began on the construction of defence systems, making new fortifications and reinforcing or repairing existing ones.

[51] The Mongol invasion temporarily stopped internal warfare among the nobles, but right after they left in the early 1240s a civil war broke out in Croatia.

A second army led by King Béla IV breached into Bosnia and forced Ban Matej Ninoslav to sign a peace treaty on 20 July 1244.

[67][68] The later kings sought to restore their influence by giving certain privileges to the towns, making them free royal cities, thus separating them from the authority of the local nobles.

At that time the power of Paul extended from Gvozd to the Neretva, and from the Adriatic coast to the Bosna River, and only the city of Zadar remained outside his realm and under the rule of Venice.

A council in Knin was convened by the King where John Babonić was named Ban of Croatia and Dalmatia, ending the hereditary banship of the Šubić family.

He seized the royal city of Knin, which led to the removal of John Babonić from his banship and the appointment of Nicholas Felsőlendvai and later Mikcs Ákos, whose army was defeated in 1326 by Ivan Nelipić.

At the same time, Stephen II Kotromanić, Ban of Bosnia, annexed the territory between Cetina and Neretva, as well as Imotski, Duvno, Livno i Glamoč.

[76] With the Treaty King Louis gained power over the entire area of Dalmatia, from the island of Cres to Durrës in Albania, including Dubrovnik (Ragusa), which acted as an independent unit.

[89] The Ottoman Empire quickly expanded to the southern areas, where they conquered large parts of Herzegovina in 1482 and Croatian strongholds in the Neretva valley.

In 1483 an army led by Croatian Ban Matthias Geréb and the Frankopans defeated a force of around 7,000 Ottoman cavalry (known as the Akıncı) at the Battle of Una River crossing near modern-day Novi Grad.

However, the incoming Ottoman army led by Hadim Yakup Pasha (bey of the Sanjak of Bosnia), that was returning from a raid in Carniola through Croatia, forced them to make peace.

[92] Croatian population from the war-affected areas gradually started to move into safer parts of the country, while some refugees fled outside Croatia to Burgenland, Southern Hungary and the Italian coast.

[95] Pope Leo X called Croatia the forefront of Christianity (Antemurale Christianitatis) in 1519, given that several Croatian soldiers made significant contributions to the struggle against the Ottoman Empire.

Petar Berislavić spent 7 years in constant fighting with the Ottomans, faced with continuous money shortages and an insufficient number of troops, until he was killed in an ambush during the battle of Plješevica on 20 May 1520.

The Austrian Archduke was interested in the Croatian election in order to oppose Zápolya, promising at the same time to protect Croatia in turbulent period of Ottoman expansion to the west.

[100] The political situation after the battle of Mohács – the king's death, two elected rulers, Ottoman conquests and, consequently, the splitting of Hungary into three parts, changed the entire medieval relation system.