Spectral line

An absorption line is produced when photons from a hot, broad spectrum source pass through a cooler material.

The intensity of light, over a narrow frequency range, is reduced due to absorption by the material and re-emission in random directions.

By contrast, a bright emission line is produced when photons from a hot material are detected, perhaps in the presence of a broad spectrum from a cooler source.

The intensity of light, over a narrow frequency range, is increased due to emission by the hot material.

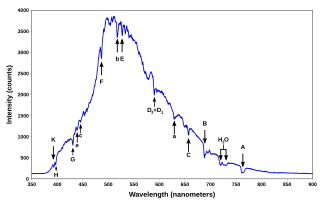

Spectral lines also depend on the temperature and density of the material, so they are widely used to determine the physical conditions of stars and other celestial bodies that cannot be analyzed by other means.

Depending on the material and its physical conditions, the energy of the involved photons can vary widely, with the spectral lines observed across the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays.

Broadening due to extended conditions may result from changes to the spectral distribution of the radiation as it traverses its path to the observer.

The natural broadening can be experimentally altered only to the extent that decay rates can be artificially suppressed or enhanced.

Each photon emitted will be "red"- or "blue"-shifted by the Doppler effect depending on the velocity of the atom relative to the observer.

This term is used especially for solids, where surfaces, grain boundaries, and stoichiometry variations can create a variety of local environments for a given atom to occupy.

Radiation emitted by a moving source is subject to Doppler shift due to a finite line-of-sight velocity projection.

At shorter wavelengths, which correspond to higher energies, ultraviolet spectral lines include the Lyman series of hydrogen.

Longer wavelengths correspond to lower energies, where the infrared spectral lines include the Paschen series of hydrogen.

At even longer wavelengths, the radio spectrum includes the 21-cm line used to detect neutral hydrogen throughout the cosmos.