Crystal growth

A crystal is a solid material whose constituent atoms, molecules, or ions are arranged in an orderly repeating pattern extending in all three spatial dimensions.

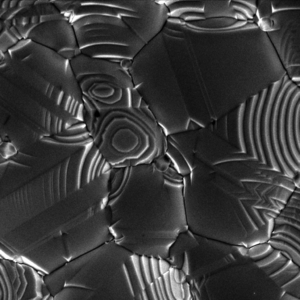

The action of crystal growth yields a crystalline solid whose atoms or molecules are close packed, with fixed positions in space relative to each other.

The crystalline state of matter is characterized by a distinct structural rigidity and very high resistance to deformation (i.e. changes of shape and/or volume).

This contrasts with most liquids or fluids, which have a low shear modulus, and typically exhibit the capacity for macroscopic viscous flow.

The reason for such rapid growth is that real crystals contain dislocations and other defects, which act as a catalyst for the addition of particles to the existing crystalline structure.

Generally, heterogeneous nucleation takes place more quickly since the foreign particles act as a scaffold for the crystal to grow on, thus eliminating the necessity of creating a new surface and the incipient surface energy requirements.

On the other hand, a badly scratched container will result in many lines of small crystals.

To achieve a moderate number of medium-sized crystals, a container which has a few scratches works best.

For perceptible growth rates, this mechanism requires a finite driving force (or degree of supercooling) in order to lower the nucleation barrier sufficiently for nucleation to occur by means of thermal fluctuations.

[5] In the theory of crystal growth from the melt, Keith Burton and Nicolás Cabrera have distinguished between two major mechanisms:[6][7][8] The surface advances by the lateral motion of steps which are one interplanar spacing in height (or some integral multiple thereof).

It is useful to consider the step as the transition between two adjacent regions of a surface which are parallel to each other and thus identical in configuration—displaced from each other by an integral number of lattice planes.

This means that in the presence of a sufficient thermodynamic driving force, every element of surface is capable of a continuous change contributing to the advancement of the interface.

For a sharp or discontinuous surface, this continuous change may be more or less uniform over large areas for each successive new layer.

For a more diffuse surface, a continuous growth mechanism may require changes over several successive layers simultaneously.

Alternatively, uniform normal growth is based on the time sequence of an element of surface.

The prediction of which mechanism will be operative under any set of given conditions is fundamental to the understanding of crystal growth.

This is in contrast to a sharp surface for which the major change in property (e.g. density or composition) is discontinuous, and is generally confined to a depth of one interplanar distance.

It is evident that the lateral growth mechanism will be found when any area in the surface can reach a metastable equilibrium in the presence of a driving force.

If the surface cannot reach equilibrium in the presence of a driving force, then it will continue to advance without waiting for the lateral motion of steps.

Thus, Cahn concluded that the distinguishing feature is the ability of the surface to reach an equilibrium state in the presence of the driving force.

He also concluded that for every surface or interface in a crystalline medium, there exists a critical driving force, which, if exceeded, will enable the surface or interface to advance normal to itself, and, if not exceeded, will require the lateral growth mechanism.

Thus, for sufficiently large driving forces, the interface can move uniformly without the benefit of either a heterogeneous nucleation or screw dislocation mechanism.

Alternatively, for sharp interfaces, the critical driving force will be very large, and most growth will occur by the lateral step mechanism.

Note that in a typical solidification or crystallization process, the thermodynamic driving force is dictated by the degree of supercooling.

The necessary thermodynamic apparatus was provided by Josiah Willard Gibbs' study of heterogeneous equilibrium.

(Prior to the discovery of carbon nanotubes, single-crystal whiskers had the highest tensile strength of any materials known).

Assuming the nucleus in such a diffusion-controlled system is a perfect sphere, the growth velocity, corresponding to the change of the radius with time

Under such diffusion controlled conditions, the polyhedral crystal form will be unstable, it will sprout protrusions at its corners and edges where the degree of supersaturation is at its highest level.

In such an unstable (or metastable) situation, minor degrees of anisotropy should be sufficient to determine directions of significant branching and growth.

The most appealing aspect of this argument, of course, is that it yields the primary morphological features of dendritic growth.