Crystallization of polymers

These chains fold together and form ordered regions called lamellae, which compose larger spheroidal structures named spherulites.

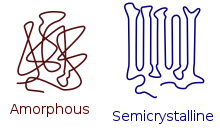

The degree of crystallinity is estimated by different analytical methods and it typically ranges between 10 and 80%, with crystallized polymers often called "semi-crystalline".

[4] Nucleation starts with small, nanometer-sized areas, where a result of heat motions in some chains or their segments occur parallel.

Those seeds can either dissociate, if thermal motion destroys the molecular order, or grow further, if the grain size exceeds a certain critical value.

[4][5] Apart from the thermal mechanism, nucleation is strongly affected by impurities, dyes, plasticizers, fillers and other additives in the polymer.

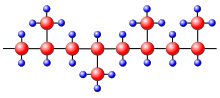

The interaction strength depends on the distance between the parallel chain segments, and it determines the mechanical and thermal properties of the polymer.

[8] The growth of the crystalline regions preferably occurs in the direction of the largest temperature gradient and is suppressed at the top and bottom of the lamellae by the amorphous folded parts at those surfaces.

[9] However, if temperature distribution is isotropic and static then lamellae grow radially and form larger quasi-spherical aggregates called spherulites.

Spherulites have a size between about 1 and 100 micrometers[3] and form a large variety of colored patterns (see, e.g. front images) when observed between crossed polarizers in an optical microscope, which often include the "Maltese cross" pattern and other polarization phenomena caused by molecular alignment within the individual lamellae of a spherulite.

[10] Polymer strength is increased not only by extrusion, but also by blow molding, which is used in the production of plastic tanks and PET bottles.

The crystal shape can be more complex for other polymers, including hollow pyramids, spirals and multilayer dendritic structures.

The rate of crystallization can be monitored by a technique which selectively probes the dissolved fraction, such as nuclear magnetic resonance.

[12] When polymers crystallize from an isotropic, bulk of melt or concentrated solution, the crystalline lamellae (10 to 20 nm in thickness) are typically organized into a spherulitic morphology as illustrated above.

However, when polymer chains are confined in a space with dimensions of a few tens of nanometers, comparable to or smaller than the lamellar crystal thickness or the radius of gyration, nucleation and growth can be dramatically affected.

In one example the large, in-plane polymer crystals reduce the gas permeability of nanolayered films by almost 2 orders of magnitude.

[4] Higher values are only achieved in materials having small molecules, which are usually brittle, or in samples stored for long time at temperatures just under the melting point.

These methods include density measurement, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), X-ray diffraction (XRD), infrared spectroscopy and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

[2][5] Another characteristic feature of semicrystalline polymers is strong anisotropy of their mechanical properties along the direction of molecular alignment and perpendicular to it.

While the crystalline regions remain unaffected by the applied stress, the molecular chains of the amorphous phase stretch.

[24] The molecular mechanism for semi-crystalline yielding involves the deformation of crystalline regions of the material via dislocation motion.

During necking, the disordered chains align along the tensile direction, forming an ordered structure that demonstrates strengthening due to the molecular reorientation.

Drawn semi-crystalline polymers are the strongest polymeric materials due to the stress-induced ordering of the molecular chains.

Semi-crystalline polymers with strong crystalline regions resist deformation and cavitation, the formation of voids in the amorphous phase, drives yielding.

It has been suggested that for particles to have a toughening effect in polymers the interparticle matrix ligament thickness must be smaller than a certain threshold.