Nucleic acid sequence

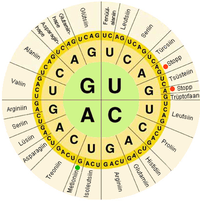

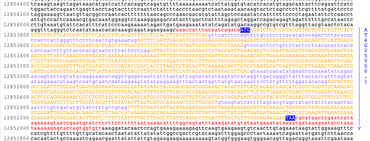

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of bases within the nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA (using GACT) or RNA (GACU) molecule.

Because nucleic acids are normally linear (unbranched) polymers, specifying the sequence is equivalent to defining the covalent structure of the entire molecule.

The nucleobases are important in base pairing of strands to form higher-level secondary and tertiary structures such as the famed double helix.

The possible letters are A, C, G, and T, representing the four nucleotide bases of a DNA strand – adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine – covalently linked to a phosphodiester backbone.

The rules of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) are as follows:[1] For example, W means that either an adenine or a thymine could occur in that position without impairing the sequence's functionality.

[1] Apart from adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), thymine (T) and uracil (U), DNA and RNA also contain bases that have been modified after the nucleic acid chain has been formed.

In RNA, there are many modified bases, including pseudouridine (Ψ), dihydrouridine (D), inosine (I), ribothymidine (rT) and 7-methylguanosine (m7G).

[3][4] Hypoxanthine and xanthine are two of the many bases created through mutagen presence, both of them through deamination (replacement of the amine-group with a carbonyl-group).

In biological systems, nucleic acids contain information which is used by a living cell to construct specific proteins.

The central dogma of molecular biology outlines the mechanism by which proteins are constructed using information contained in nucleic acids.

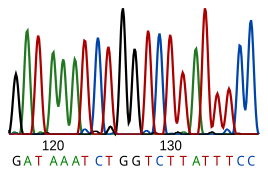

Current sequencing methods rely on the discriminatory ability of DNA polymerases, and therefore can only distinguish four bases.

The DNA in an organism's genome can be analyzed to diagnose vulnerabilities to inherited diseases, and can also be used to determine a child's paternity (genetic father) or a person's ancestry.

Therefore, it does not account for possible differences among organisms or species in the rates of DNA repair or the possible functional conservation of specific regions in a sequence.

More statistically accurate methods allow the evolutionary rate on each branch of the phylogenetic tree to vary, thus producing better estimates of coalescence times for genes.

The manipulations of the information profiles enable the analysis of the sequences using alignment-free techniques, such as for example in motif and rearrangements detection.