Dalmatian Italians

Following the positive trend observed during the last decade (i.e., after the dissolution of Yugoslavia), the number of Dalmatian Italians in Croatia adhering to the CNI has risen to around one thousand.

[12] In the Early Middle Ages, the territory of the Byzantine province of Dalmatia reached in the North up to the river Sava, and was part of the Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum.

In the middle of the 6th and the beginning of the 7th century began the Slavic migration, which caused the Romance-speaking population, descendants of Romans and Illyrians (speaking Dalmatian), to flee to the coast and islands.

The Venetians could afford to concede relatively generous terms because their own principal aims was not the control of the territory sought by Hungary, but the economic suppression of any potential commercial competitors on the eastern Adriatic.

This aim brought on the necessity of enforced economic stagnation for the Dalmatian city-states, while the Hungarian feudal system promised greater political and commercial autonomy.

[15] The farmers and the merchants who traded in the interior naturally favoured Hungary, their most powerful neighbour on land; while the seafaring community looked to Venice as mistress of the Adriatic.

[15] The doubtful allegiance of the Dalmatians tended to protract the struggle between Venice and Hungary, which was further complicated by internal discord due largely to the spread of the Bogomil heresy; and by many outside influences, such as the vague suzerainty still enjoyed by the Eastern emperors during the 12th century; the assistance rendered to Venice by the armies of the Fourth Crusade in 1202; and the Tatar invasion of Dalmatia forty years later (see Trogir).

[15] In 1409, during the 20-year Hungarian civil war between King Sigismund and the Neapolitan house of Anjou, the losing contender, Ladislaus of Naples, sold his claim on Dalmatia to the Venetian Republic for a meager sum of 100,000 ducats.

This process was aided by the constant migration between the Adriatic cities and involved even the independent Dubrovnik (Ragusa) and the port of Rijeka (Fiume).

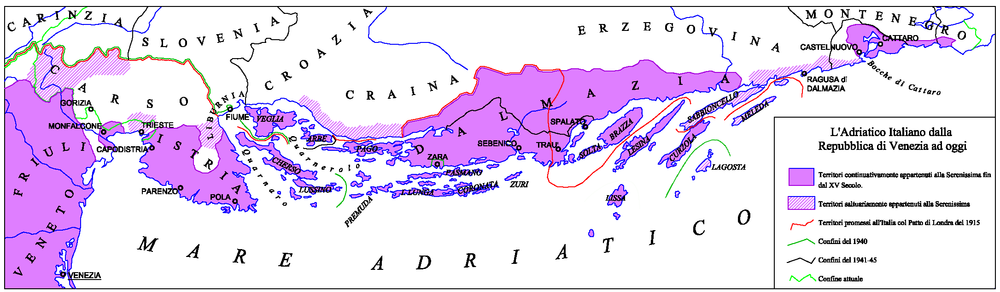

However, after 1866, when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom of Italy, Dalmatia remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic.

[19] During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavicization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[20] His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard.

The Unionist faction won the elections in Dalmatia in 1870, but they were prevented from following through with the merge with Croatia and Slavonia due to the intervention of the Austrian imperial government.

Starting from the 1840s, large numbers of the Italian minority were passively croatized, or had emigrated as a consequence of the unfavorable economic situation.

[3][4] Bartoli's evaluation was followed by other claims that Auguste de Marmont, the French Governor General of the Napoleonic Illyrian Provinces commissioned a census in 1814–1815 which found that Dalmatian Italians comprised 29 percent of the total population of Dalmatia.

The pact was nullified in the Treaty of Versailles due to the objections of American president Woodrow Wilson and the South Slavic delegations.

However, in 1920 the Kingdom of Italy managed to get after the Treaty of Rapallo, most of the Austrian Littoral, part of Inner Carniola, some border areas of Carinthia, the city of Zadar along with the island and Lastovo.

A large number of Italians (allegedly nearly 20,000) moved from the areas of Dalmatia assigned to Yugoslavia and resettled in Italy (mainly in Zara).

In November 1918, after the surrender of Austria-Hungary, Italy occupied militarily Trentino Alto-Adige, the Julian March, Istria, the Kvarner Gulf and Dalmatia, all Austro-Hungarian territories.

This included the shutting down of educational facilities in Slavic languages, forced Italianization of citizen's names, and the brutal persecution of dissenters.

Where in the 19th century there was conflict only on the upper classes, there was now an increasing mutual hatred present in varying degrees among the entire population.

Due to the restrictions imposed to the double nationality of the Italian minority in Yugoslavia after 1945, this requirement could only be met by a limited number of children.

After considerable government opposition,[39][40] with the imposition of a national filter that imposed the obligation to possess Italian citizenship for registration, and by 2013 it was opened hosting the first 25 children.

From Giorgio Orsini to the influence on the early contemporary Croatian literature, Venice made its Dalmatia the most western-oriented civilized area of the Balkans, mostly in the cities.

Some architectural works from that period of Dalmatia are of European importance, and would contribute to further development of the Renaissance: the Cathedral of St James in Šibenik and the Chapel of Blessed John in Trogir.

The beginning of the Croatian 16th-century literal activity was marked by a Dalmatian humanist Marco Marulo and his epic book Judita, which has been written by incorporating peculiar motives and events from the classical Bible, and adapting them to the contemporary literature in Europe.

[50] In 1997 the historical city-island of Trogir (called "Tragurium" in Latin when was one of the Dalmatian City-States and "Traù" in venetian) was inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Trogir's grandest building is the church of St. Lawrence, whose main west portal is a masterpiece by Radovan, and the most significant work of the Romanesque-Gothic style in Croatia.

The new forms which he introduced were eagerly imitated and developed by other architects, until the period of decadence - which virtually concludes the history of Dalmatian art - set in during the latter half of the 17th century.

The Il Regio Dalmata – Kraglski Dalmatin was stamped in the typography of the Dalmatian Italian Antonio Luigi Battara and was the first done in Croatian.

[56] Andrea Alibranti has proposed that the first appearance of the dance in Korčula came after the defeat of the corsair Uluz Ali by the local inhabitants in 1571.