David A. Johnston

A principal scientist on the USGS monitoring team, Johnston was killed in the eruption while manning an observation post six miles (10 km) away on the morning of May 18, 1980.

before he was swept away by a lateral blast; despite a thorough search, Johnston's body was never found, but state highway workers discovered remnants of his USGS trailer in 1993.

[5][6] Johnston spent the summer after college in the San Juan volcanic field of Colorado working with volcanologist Pete Lipman in his study of two extinct calderas.

[8] During the summers of 1978 and 1979, Johnston led studies of the ash-flow sheet emplaced in the 1912 eruption of Mount Katmai in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.

Because of this, Johnston mastered the many techniques required to analyze glass-vapor inclusions in phenocrysts embedded in lavas, which provide information about gases present during past eruptions.

His work at Mount Katmai and other volcanoes in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes paved the way for his career, and his "agility, nerve, patience, and determination around the jet-like summit fumaroles in the crater of Mt.

[5] Later in 1978, Johnston joined the United States Geological Survey (USGS), where he monitored volcanic emission levels in the Cascades and Aleutian Arc.

[9] Fellow volcanologist Wes Hildreth said of Johnston, "I think Dave's dearest hope was that systematic monitoring of fumarolic emissions might permit detection of changes characteristically precursory to eruptions ... Dave wanted to formulate a general model for the behavior of magmatic volatiles prior to explosive outbursts and to develop a corollary rationale for the evaluation of hazards.

"[5] During this time, Johnston continued to visit Mount Augustine every summer and also assessed the geothermal energy potential of the Azores and Portugal.

In the last year of his life, Johnston developed an interest in the health, agricultural, and environmental effects of both volcanic and anthropogenic emissions to the atmosphere.

[11] Similar activity continued at the volcano over the following weeks, excavating the crater, forming an adjacent caldera, and erupting small amounts of steam, ash, and tephra.

[14] Given the increasing seismic and volcanic activity, Johnston and the other volcanologists working for the USGS in its Vancouver branch prepared to observe any impending eruption.

Worried that the amount of pressure on the magma underground was increasing, scientists analyzed gases by the crater, and found high traces of sulfur dioxide.

In a matter of seconds, vibrations from the earthquake loosened 2.7 cubic kilometers (0.6 cu mi) of rock on the mountain's north face and summit, creating a massive landslide.

[19] With the loss of the confining pressure of the overlying rock, Mount St. Helens began to rapidly emit steam and other volcanic gases.

[20] Before being struck by a series of flows that, at their fastest, would have taken less than a minute to reach his position 46°16′37.5″N 122°13′28.0″W / 46.277083°N 122.224444°W / 46.277083; -122.224444, Johnston attempted to radio his USGS co-workers with the message: "Vancouver!

[21] Initially, there was some debate as to whether Johnston had survived; records soon showed a radio message from fellow eruption victim and amateur radio operator Gerry Martin, located near the Coldwater peak 46°17′59.7″N 122°12′55″W / 46.299917°N 122.21528°W / 46.299917; -122.21528 and farther north of Johnston's position, reporting his sighting of the eruption enveloping the Coldwater II observation post.

As the blast overwhelmed Johnston's post, Martin declared solemnly: "Gentlemen, the camper and car that’s sitting over to the south of me is covered.

These six photographs, taken sideways on to the lateral blast, vividly show the extent and size of the avalanche and flows as they reached northwards over and beyond Johnston's position.

[25] Famous for telling reporters that being on the mountain was like "standing next to a dynamite keg and the fuse is lit",[27] Johnston had been among the first volcanologists at the volcano when eruptive signs appeared, and shortly after was named the head of volcanic gas monitoring.

Many USGS scientists worked on the team monitoring the volcano, but it was graduate student Harry Glicken who had been manning the Coldwater II observation post for the two and a half weeks immediately preceding the eruption.

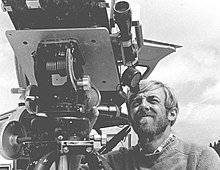

[30] Just prior to his departure, at 7 p.m. on the evening of May 17, 13½ hours before the eruption, Glicken took the famous photograph of Johnston sitting by the observation-post trailer with a notebook on his lap, smiling.

[32] Frantic and guilt-stricken, Harry Glicken convinced three separate helicopter pilots to take him up on flights over the devastated area in a rescue attempt, but the eruption had so changed the landscape that they were unable to locate any sign of the Coldwater II observation post.

[34] The public was shocked by the extent of the eruption, which had lowered the elevation of the summit by 1,313 feet (400 m), destroyed 230 square miles (600 km2) of woodland, and spread ash into other states and Canada.

[35] Two years after the eruption, the United States government set aside 110,000 acres (450 km2) of land for the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument.

[9] An obituary notice for Johnston stated that at the time of his death he had been "among the leading young volcanologists in the world" and that his "enthusiasm and warmth" would be "missed at least as much as his scientific strength".

Measurements of surface deformation due to magmatic intrusions, like those that were conducted by Johnston and the other USGS scientists at the Coldwater I and II outposts, have advanced in scale and precision.

[47] Johnston's connections with the University of Washington (where he had carried out his masters and doctoral research) are remembered by a memorial fund that established an endowed graduate-level fellowship within what is now the department of Earth and Space Sciences.

[49] Located just over 5 miles (8 km) from the north flank of Mount St. Helens, the Johnston Ridge Observatory (JRO) allows the public to admire the open crater, new activity, and the creations of the 1980 eruption, including an extensive basalt field.

[21] Johnston's mother stated that the film had changed many true aspects of the eruption, and depicted her son as "a rebel" with "a history of disciplinary trouble".