1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens

On March 27, 1980, a series of volcanic explosions and pyroclastic flows began at Mount St. Helens in Skamania County, Washington, United States.

The eruption was preceded by a two-month series of earthquakes and steam-venting episodes caused by an injection of magma at shallow depth below the volcano that created a large bulge and a fracture system on the mountain's north slope.

An earthquake at 8:32:11 am PDT (UTC−7) on May 18, 1980,[3] caused the entire weakened north face to slide away, a sector collapse which was the largest subaerial landslide in recorded history.

[6] At the same time, snow, ice, and several entire glaciers on the volcano melted, forming a series of large lahars (volcanic mudslides) that reached as far as the Columbia River, nearly 50 miles (80 km) to the southwest.

[7] About 57 people were killed, including innkeeper and World War I veteran Harry R. Truman, photographers Reid Blackburn and Robert Landsburg, and volcanologist David A.

[26] A USGS team determined in the last week of April that a 1.5 mi-diameter (2.4 km) section of St. Helens's north face was displaced outward by at least 270 ft (82 m).

Because the intruding magma remained below ground and was not directly visible, it was called a cryptodome, in contrast to a true lava dome exposed at the surface.

The rates of bulge movement and sulfur dioxide emission, and ground temperature readings did not reveal any changes indicating a catastrophic eruption.

[9] Some of the slide spilled over the ridge, but most of it moved 13 mi (21 km) down the North Fork Toutle River, filling its valley up to 600 feet (180 m) deep with avalanche debris.

Some of these remained intact with roots, but most had been sheared off at the stump seconds earlier by the blast of superheated volcanic gas and ash that had immediately followed and overtaken the initial landslide.

The rest of the trees, especially those that were not completely detached from their roots, were turned upright by their own weight and became waterlogged, sinking into the muddy sediments at the bottom where they are in the process of becoming petrified in the anaerobic and mineral-rich waters.

Superheated flow material flashed water in Spirit Lake and North Fork Toutle River to steam, creating a larger, secondary explosion that was heard as far away as British Columbia,[36] Montana, Idaho, and Northern California, yet many areas closer to the eruption (Portland, Oregon, for example) did not hear the blast.

This so-called "quiet zone" extended radially a few tens of miles from the volcano and was created by the complex response of the eruption's sound waves to differences in temperature and air motion of the atmospheric layers, and to a lesser extent, local topography.

The area affected by the blast can be subdivided into roughly concentric zones:[9] By the time this pyroclastic flow hit its first human victims, it was still as hot as 680 °F (360 °C) and filled with suffocating gas and flying debris.

As the blast overwhelmed Johnston's post, Martin declared solemnly: "Gentlemen, the camper and car that's sitting over to the south of me is covered.

[39][40] Subsequent outpourings of pyroclastic material from the breach left by the landslide consisted mainly of new magmatic debris rather than fragments of pre-existing volcanic rocks.

[9] Secondary steam-blast eruptions fed by this heat created pits on the northern margin of the pyroclastic-flow deposits, at the south shore of Spirit Lake, and along the upper part of the North Fork Toutle River.

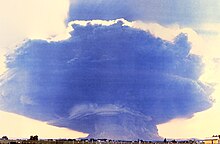

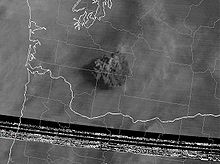

[9] As the avalanche and initial pyroclastic flow were still advancing, a huge ash column grew to a height of 12 mi (19 km) above the expanding crater in less than 10 minutes and spread tephra into the stratosphere for 10 straight hours.

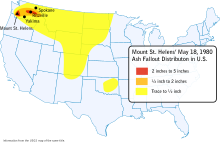

[36] Continuing eastward,[42] St. Helens's ash fell in the western part of Yellowstone National Park by 10:15 pm, and was seen on the ground in Denver the next day.

As in many previous St. Helens eruptions, this created huge lahars (volcanic mudflows) and muddy floods that affected three of the four stream drainage systems on the mountain,[41] and which started to move as early as 8:50 am.

Bridges were taken out at the mouth of Pine Creek and the head of Swift Reservoir, which rose 2.6 ft (0.79 m)[41] by noon to accommodate the nearly 18,000,000 cu yd (14,000,000 m3) of additional water, mud, and debris.

Ninety minutes after the eruption, the first mudflow had moved 27 mi (43 km) upstream, where observers at Weyerhaeuser's Camp Baker saw a 12 ft-high (4 m) wall of muddy water and debris pass.

Another estimated 40,000 young salmon were killed when they swam through turbine blades of hydroelectric generators after reservoir levels were lowered along the Lewis River to accommodate possible mudflows and flood waters.

Backpacks belonging to them had been found in July 1980, but a layer of ash deposited by the eruption may have hid the bodies, also preventing animals disturbing the remains.

Air travel was disrupted for between a few days and two weeks, as several airports in eastern Washington shut down because of ash accumulation and poor visibility.

State and federal agencies estimated that over 2,400,000 cu yd (1,800,000 m3) of ash, equivalent to about 900,000 tons in weight, were removed from highways and airports in Washington.

A supplemental appropriation of $951 million for disaster relief was voted by Congress, of which the largest share went to the Small Business Administration, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Not only was tourism down in the Mount St. Helens–Gifford Pinchot National Forest area, but conventions, meetings and social gatherings also were cancelled or postponed at cities and resorts elsewhere in Washington and neighboring Oregon not affected by the eruption.

Erratic wind from the storm carried ash from the eruption to the south and west, lightly dusting large parts of western Washington and Oregon.

[57] This event caused the Portland area, previously spared by wind direction, to be thinly coated with ash in the middle of the annual Rose Festival.