De motu corporum in gyrum

[3] After further encouragement from Halley, Newton developed the ideas outlined by De Motu into his book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica.

One of the surviving copies of De Motu was made by being entered in the Royal Society's register book, and its (Latin) text is available online.

(Newton uses for this derivation – as he does in later proofs in this De Motu, as well as in many parts of the later Principia – a limit argument of infinitesimal calculus in geometric form,[7] in which the area swept out by the radius vector is divided into triangle-sectors.

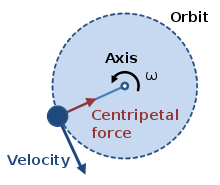

Theorem 3 now evaluates the centripetal force in a non-circular orbit, using another geometrical limit argument, involving ratios of vanishingly small line-segments.

Here Newton finds the centripetal force to produce motion in this configuration would be inversely proportional to the square of the radius vector.

He also identifies a geometrical criterion for distinguishing between the elliptical case and the others, based on the calculated size of the latus rectum, as a proportion to the distance the orbiting body at closest approach to the center.

Finally in the series of propositions based on zero resistance from any medium, Problem 5 discusses the case of a degenerate elliptical orbit, amounting to a straight-line fall towards or ejection from the attracting center.

Then a final scholium points out how problems 6 and 7 apply to the horizontal and vertical components of the motion of projectiles in the atmosphere (in this case neglecting earth curvature).

Newton's style of demonstration in all his writings was rather brief in places; he appeared to assume that certain steps would be found self-evident or obvious.

The proof of the converse here depends on its being apparent that there is a unique relation, i.e., that in any given setup, only one orbit corresponds to one given and specified set of force/velocity/starting position.

Newton added a mention of this kind into the second edition of the Principia, as a Corollary to Propositions 11–13, in response to criticism of this sort made during his lifetime.

[8] A significant scholarly controversy has existed over the question whether and how far these extensions to the converse, and the associated uniqueness statements, are self-evident and obvious or not.

According to one of these reminiscences, Halley asked Newton, "what he thought the Curve would be that would be described by the Planets supposing the force of attraction towards the Sun to be reciprocal to the square of their distance from it.

"[12] Another version of the question was given by Newton himself, but also about thirty years after the event: he wrote that Halley, asking him "if I knew what figure the Planets described in their Orbs about the Sun was very desirous to have my Demonstration"[13] In light of these differing reports, both produced from old memories, it is hard to know exactly what words Halley used.

Newton acknowledged in 1686 that an initial stimulus on him in 1679/80 to extend his investigations of the movements of heavenly bodies had arisen from correspondence with Robert Hooke in 1679/80.

[16] Newton did acknowledge some prior work of others, including Ismaël Bullialdus, who suggested (but without demonstration) that there was an attractive force from the Sun in the inverse square proportion to the distance, and Giovanni Alfonso Borelli, who suggested (again without demonstration) that there was a tendency towards the Sun like gravity or magnetism that would make the planets move in ellipses; but that the elements Hooke claimed were due either to Newton himself, or to other predecessors of them both such as Bullialdus and Borelli, but not Hooke.