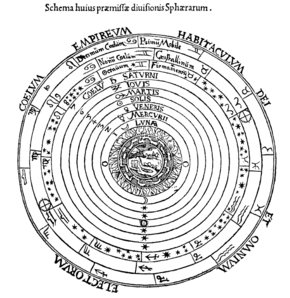

Celestial spheres

In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed stars and planets are accounted for by treating them as embedded in rotating spheres made of an aetherial, transparent fifth element (quintessence), like gems set in orbs.

[5] Albert Van Helden has suggested that from about 1250 until the 17th century, virtually all educated Europeans were familiar with the Ptolemaic model of "nesting spheres and the cosmic dimensions derived from it".

In Greek antiquity the ideas of celestial spheres and rings first appeared in the cosmology of Anaximander in the early 6th century BC.

But whilst the stars are fastened on a revolving crystal sphere like nails or studs, the Sun, Moon, and planets, and also the Earth, all just ride on air like leaves because of their breadth.

The most enduring feature of Anaximenes' cosmos was its conception of the stars being fixed on a crystal sphere as in a rigid frame, which became a fundamental principle of cosmology down to Copernicus and Kepler.

[10] And much later in the fourth century BC Plato's Timaeus proposed that the body of the cosmos was made in the most perfect and uniform shape, that of a sphere containing the fixed stars.

[14] Although historians of Greek science have traditionally considered these models to be merely geometrical representations,[15][16] recent studies have proposed that they were also intended to be physically real[17] or have withheld judgment, noting the limited evidence to resolve the question.

[33] In his Zij, Al-Battānī presented independent calculations of the distances to the planets on the model of nesting spheres, which he thought was due to scholars writing after Ptolemy.

[34] Around the turn of the millennium, the Arabic astronomer and polymath Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen) presented a development of Ptolemy's geocentric models in terms of nested spheres.

[36] Near the end of the twelfth century, the Spanish Muslim astronomer al-Bitrūjī (Alpetragius) sought to explain the complex motions of the planets without Ptolemy's epicycles and eccentrics, using an Aristotelian framework of purely concentric spheres that moved with differing speeds from east to west.

[34] About the same time, scholars in European universities began to address the implications of the rediscovered philosophy of Aristotle and astronomy of Ptolemy.

[45][46] General understanding of the dimensions of the universe derived from the nested sphere model reached wider audiences through the presentations in Hebrew by Moses Maimonides, in French by Gossuin of Metz, and in Italian by Dante Alighieri.

Adi Setia describes the debate among Islamic scholars in the twelfth century, based on the commentary of Fakhr al-Din al-Razi about whether the celestial spheres are real, concrete physical bodies or "merely the abstract circles in the heavens traced out… by the various stars and planets."

Setia points out that most of the learned, and the astronomers, said they were solid spheres "on which the stars turn… and this view is closer to the apparent sense of the Qur'anic verses regarding the celestial orbits."

Setia concludes: "Thus it seems that for al-Razi (and for others before and after him), astronomical models, whatever their utility or lack thereof for ordering the heavens, are not founded on sound rational proofs, and so no intellectual commitment can be made to them insofar as description and explanation of celestial realities are concerned.

"[48] Christian and Muslim philosophers modified Ptolemy's system to include an unmoved outermost region, the empyrean heaven, which came to be identified as the dwelling place of God and all the elect.

[54] His views were challenged by al-Jurjani (1339–1413), who maintained that even if the celestial spheres "do not have an external reality, yet they are things that are correctly imagined and correspond to what [exists] in actuality".

[55] By the end of the Middle Ages, the common opinion in Europe was that celestial bodies were moved by external intelligences, identified with the angels of revelation.

[57] Early in the sixteenth century Nicolaus Copernicus drastically reformed the model of astronomy by displacing the Earth from its central place in favour of the Sun, yet he called his great work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres).

[59] The English almanac maker, Thomas Digges, delineated the spheres of the new cosmological system in his Perfit Description of the Caelestiall Orbes … (1576).

"[60] In the sixteenth century, a number of philosophers, theologians, and astronomers—among them Francesco Patrizi, Andrea Cisalpino, Peter Ramus, Robert Bellarmine, Giordano Bruno, Jerónimo Muñoz, Michael Neander, Jean Pena, and Christoph Rothmann—abandoned the concept of celestial spheres.

[64][65] In his early Mysterium Cosmographicum, Johannes Kepler considered the distances of the planets and the consequent gaps required between the planetary spheres implied by the Copernican system, which had been noted by his former teacher, Michael Maestlin.

"[72] The late-16th-century Portuguese epic The Lusiads vividly portrays the celestial spheres as a "great machine of the universe" constructed by God.