Death poem

The death poem is a genre of poetry that developed in the literary traditions of the Sinosphere—most prominently in Japan as well as certain periods of Chinese history, Joseon Korea, and Vietnam.

It is a concept or worldview derived from the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence (三法印, sanbōin), specifically that the material world is transient and impermanent (無常, mujō), that attachment to it causes suffering (苦, ku), and ultimately all reality is an emptiness or absence of self-nature (空, kū).

According to comparative religion scholar Julia Ching, Japanese Buddhism "is so closely associated with the memory of the dead and the ancestral cult that the family shrines dedicated to the ancestors, and still occupying a place of honor in homes, are popularly called the Butsudan, literally 'the Buddhist altars'.

It was introduced to Western audiences during World War II when Japanese soldiers, emboldened by their culture's samurai legacy, would write poems before suicidal missions or battles.

Yuan met his end when he was arrested and executed by lingchi ("slow slicing") on the order of the Chongzhen Emperor under false charges of treason, which were believed to have been planted against him by the Jurchens.

A life's work totals to nothing Half of my career seems to be in dreams I do not worry about lacking brave warriors after my death For my loyal spirit will continue to guard Liaodong Xia Wanchun (夏完淳, 1631–1647) was a Ming dynasty poet and soldier.

[9] Excepting the earliest works of this tradition, it has been considered inappropriate to mention death explicitly; rather, metaphorical references such as sunsets, autumn or falling cherry blossom suggest the transience of life.

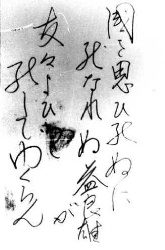

夜もすがら 契りし事を 忘れずは こひむ涙の 色ぞゆかしき 知る人も なき别れ路に 今はとて 心ぼそくも 急ぎたつかな 烟とも 雲ともならぬ 身なれども 草葉の露を それとながめよ

yo mosu gara / chigirishi koto o / wasurezu wa/ kohimu namida no/ irozo yukashiki shiru hito mo/naki wakare chi ni / ima wa tote / kokoro bosoku mo / isogi tasu kana kemuri tomo / kumo tomo naranu / mi nare domo / kusaba no tsuyu wo / sore to nagame yo

I leave this road, unseen by friend or kin, No kindly hand to guide these trembling feet; My fragile heart, a withered leaf within, Treads toward that dusky realm in lone retreat.

Though urged to hasten far beyond this shore, My mind is frail, and tears outlast the day; If not to vanish, smoke or cloud, once more, Gaze on the dew that glistens where I lay.

—— Translation adapted to Shakespearean Sonnet form On March 17, 1945, General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, the Japanese commander-in chief during the Battle of Iwo Jima, sent a final letter to Imperial Headquarters.

国の為 重き努を 果し得で 矢弾尽き果て 散るぞ悲しき 仇討たで 野辺には朽ちじ 吾は又 七度生れて 矛を執らむぞ 醜草の 島に蔓る 其の時の 皇国の行手 一途に思ふ

[13] In 1970, writer Yukio Mishima and his disciple Masakatsu Morita composed death poems before their attempted coup at the Ichigaya garrison in Tokyo, where they committed seppuku.

Falling ill on a journey my dreams go wandering over withered fields[16] Despite the seriousness of the subject matter, some Japanese poets have employed levity or irony in their final compositions.

Written over a large calligraphic character 死 shi, meaning Death, the Japanese Zen master Hakuin Ekaku (白隠 慧鶴; 1685–1768) wrote as his jisei: 若い衆や死ぬがいやなら今死にやれ 一たび死ねばもう死なぬぞや

However, better-known examples are those written or recited by famous historical figures facing death when they were executed for loyalty to their former king or due to insidious plot.

These examples are written in Korean sijo (three lines of 3-4-3-4 or its variation) or in Hanja five-syllable format (5-5-5-5 for a total of 20 syllables) of ancient Chinese poetry (五言詩).

[18] 방(房) 안에 혓는 촉(燭) 불 눌과 이별(離別)하엿관대 것츠로 눈믈 디고 속 타는 쥴 모르는고.

擊鼓催人命 (격고최인명) -둥둥 북소리는 내 생명을 재촉하고, 回頭日欲斜 (회두일욕사) -머리를 돌여 보니 해는 서산으로 넘어 가려고 하는구나 黃泉無客店 (황천무객점) -황천으로 가는 길에는 주막조차 없다는데, 今夜宿誰家 (금야숙수가) -오늘밤은 뉘 집에서 잠을 자고 갈거나

愛君如愛父 (애군여애부) -임금 사랑하기를 아버지 사랑하듯 하였고 憂國如憂家 (우국여우가) -나라 걱정하기를 집안 근심처럼 하였다 白日臨下土 (백일임하토) -밝은 해 아래 세상을 굽어보사 昭昭照丹衷 (소소조단충) -내 단심과 충정 밝디 밝게 비춰주소서

가을 밤 등불아래 책을 덮고서 옛일 곰곰이 생각해 보니, 인간 세상에서 지식인 노릇하기가 참으로 어렵구나.

Birds and beasts cry in sorrow and the mountains and oceans frown The three thousand li of hibiscuses have sunken underwater As I closed a book under a lamp and thought about the past on an autumn night, It's difficult to be an intellectual in this human world.

Thấy nghĩa lòng đâu dám hững hờ Làm trai trung hiếu quyết tôn thờ Thân này sống chết khôn màng nhắc Thương bấy mẹ già tóc bạc phơ

In collaboration with Lê Duy Uẩn (黎維蘊) and Nguyễn Thịnh (阮盛), Hoàng Phan Thái sought to overthrow Tự Đức’s regime through a military uprising and to resist the French colonialists.

[25] Their strategy involved leveraging coastal forces and rallying support in the Nghệ Tĩnh region, with plans to weaken the Nguyễn dynasty's central power.

In July 1519, during a heavy rainstorm, Lê Chiêu Tông's general, Mạc Đăng Dung (莫登庸), led both naval and land forces to besiege Emperor Thiên Hiến at Từ Liêm.

Những toan phục nước cứu muôn dân Trời chẳng chiều người cũng khó phần Sông rộng, Giang Đông khôn trở gót Gió to, Xích Bích dễ thiêu quân Ninh Sơn mây ám rồng xa khuất Phúc địa trăng soi hạc tới gần.

Dark clouds cover Ninh Mountain as the dragon flies far, The bright moon shines on the blessed land where cranes come frequently.

Phan Thanh Giản was a Nguyễn dynasty official who held position of Hiệp biện Đại học sĩ (協辦大學士; Assistant to the Grand Secretariat).