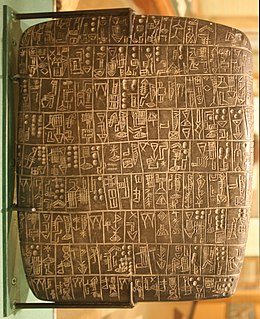

Decipherment of cuneiform

Actual decipherment did not take place until the beginning of the 19th century, initiated by Georg Friedrich Grotefend in his study of Old Persian cuneiform.

[6] In the 15th century, the Venetian Giosafat Barbaro explored ancient ruins in the Middle East and came back with news of a very odd writing he had found carved on the stones in the temples of Shiraz and on many clay tablets.

Antonio de Gouvea, a professor of theology, noted in 1602 the strange writing he had seen during his travels a year earlier in Persia.

[7][8][9] In 1625, the Roman traveler Pietro Della Valle, who had sojourned in Mesopotamia between 1616 and 1621, brought to Europe copies of characters he had seen in Persepolis and inscribed bricks from Ur and the ruins of Babylon.

[10][11] The copies he made, the first that reached circulation within Europe, were not quite accurate, but Della Valle understood that the writing had to be read from left to right, following the direction of wedges.

[16][17] Carsten Niebuhr brought very complete and accurate copies of the inscriptions at Persepolis to Europe, published in 1767 in Reisebeschreibungen nach Arabien ("Account of travels to Arabia and other surrounding lands").

[16][22] At about the same time, Anquetil-Duperron came back from India, where he had learnt Pahlavi and Persian under the Parsis, and published in 1771 a translation of the Zend Avesta, thereby making known Avestan, one of the ancient Iranian languages.

[28][29] By looking at the length of the character sequences in the Niebuhr inscriptions 1 & 2, comparing with the names and genealogy of the Achaemenid kings as known from the Greeks, and taking into account the fact that according to this genealogy the father of two of the Achaemenid rulers were not kings and therefore should not have this attribute in the inscriptions, Grotefend correctly guessed the identity of the rulers.

[35][36] This time, academics took note, particularly Eugène Burnouf and Rasmus Christian Rask, who would expand on Grotefend's work and further advance the decipherment of cuneiforms.

[34] In 1836, the eminent French scholar Eugène Burnouf discovered that the first of the inscriptions published by Niebuhr contained a list of the satrapies of Darius.

[5]: 14 [39][40] A month earlier, a friend and pupil of Burnouf's, Professor Christian Lassen of Bonn, had also published his own work on The Old Persian Cuneiform Inscriptions of Persepolis.

[40][41] He and Burnouf had been in frequent correspondence, and his claim to have independently detected the names of the satrapies, and thereby to have fixed the values of the Persian characters, was consequently fiercely attacked.

He succeeded in fixing the true values of nearly all the letters in the Persian alphabet, in translating the texts, and in proving that the language of them was not Zend, but stood to both Zend and Sanskrit in the relation of a sister.Meanwhile, in 1835 Henry Rawlinson, a British East India Company army officer, visited the Behistun Inscriptions in Persia.

Carved in the reign of King Darius of Persia (522–486 BC), they consisted of identical texts in the three official languages of the empire: Old Persian, Babylonian and Elamite.

[5]: 17 After translating Old Persian, Rawlinson and, working independently of him, the Irish Assyriologist Edward Hincks, began to decipher the other cuneiform scripts in the Behistun Inscription.

[46][47][48] They were greatly helped by the excavations of the French naturalist Paul Émile Botta and English traveler and diplomat Austen Henry Layard of the city of Nineveh from 1842.

They were soon joined by two other decipherers: young German-born scholar Julius Oppert, and versatile British Orientalist William Henry Fox Talbot.

Edwin Norris, the secretary of the Royal Asiatic Society, gave each of them a copy of a recently discovered inscription from the reign of the Assyrian emperor Tiglath-Pileser I.

The inexperienced Talbot had made a number of mistakes, and Oppert's translation contained a few doubtful passages which the jury politely ascribed to his unfamiliarity with the English language.

[52] In November 2023, generative artificial intelligence managed to make accurate records of cuneiform writing with a three-dimensional scan and model capable of appreciating the depth of the impression left by the stylus in the clay and the distance between the symbols and the wedges.