Decline and fall of Pedro II of Brazil

It coincided with a period of economic and social stability and progress for the Empire of Brazil, with the nation achieving a prominent place as an emerging power in the international arena.

The royal family's indifference to the Imperial system allowed a discontented republican minority to grow bolder and eventually launch the coup that overthrew the Empire.

[11] Topik continues: "Factories also sprang throughout the Brazilian Empire in the 1880s at an unprecedented rate, and its cities were beginning to receive the benefits of gas, electrical, sanitation, telegraph, and tram companies.

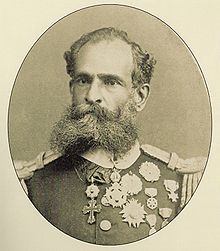

The remarks made by a former U.S. consul at Rio de Janeiro, who met Pedro II in late 1882, tell much of the general view that foreigners had of Brazil and its Emperor by the end of the 1880s:[27] Dom Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil … has an intellectual head, eyes a grayish blue … beard full and gray, hair well trimmed, also gray, complexion florid, and expression sober.

He is erect, and has a manly bearing … During this long period [of his rule] there have been some provincial rebellions and some local turmoil, but the Emperor has always shown tact, energy, and humanity that helped much to restore order, quite, and good feeling.

[29] Brazilian writer Machado de Assis would later remember him as "a humble, honest, well-learned and patriotic man, who knew how to make of a throne a chair [for his simplicity], without diminishing its greatness and respect.

"[32] But although Brazil was richer and more powerful than ever, and gained an excellent international reputation, and Pedro II himself was still extremely popular among his subjects, the Brazilian monarchy itself was dying.

[37] He was observed walking the streets in a tailcoat and carrying an umbrella, sometimes surrounded by cheerful children;[38] sampling fruits in the local market; and tasting the students' food in the kitchens on visits to schools.

"[44] These elder statesmen began to die off or retire from the government until, by the 1880s, they had almost entirely been replaced by a younger generation of politicians who had no experience of the Regency and early years of Pedro II's reign, when external and internal dangers threatened the nation's existence.

Emperor Pedro II was the last of the direct male line in Brazil descended from Dom Afonso I, first king of Portugal and founder, in 1139, of the dynasty which headed the Brazilian Empire.

[56] A weary emperor who no longer cared for the throne, an heir who had no desire to assume the crown, discontent among ruling circles who were dismissive of the Imperial role in national affairs: all seemed to presage the monarchy's impending doom.

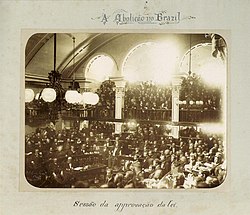

[58] Republicanism—either support for a presidential or parliamentary republic—as an enduring political movement appeared in Brazil during December 1870 in Rio de Janeiro with the publishing of a manifesto signed by 57 people and with the creation of the Republican Club.

"[69] Its numbers only increased after 1888, adding new adherents consisting of farmers who had been slave owners and who perceived themselves victims of an unjust abolition of slavery that had not included any type of indemnity to them.

"[76] In the "political process of the second empire [reign of Pedro II], the republican party had such a dull and secondary role that it might even have been forgotten; it was unable to influence rationales advocating the regime's dissolution.

[63] The Marquis of São Vicente, then President of the Council of Ministers, suggested to the emperor that republicans be forbidden to enter into public service, a practice then common in monarchies.

[86] The older generation of officers were loyal to the monarchy, believed the military should be under civilian control, and had a great aversion to the militaristic caudillism against which they had earlier fought.

But Princess Isabel, acting regent on behalf of her father who was in Europe, instead opted to dismiss the entire cabinet and support the so-called "undisciplined military faction".

[89] Even so, Positivists still expected to make a peaceful transition to their fantasy of a republican dictatorship and Constant, who had also taught the emperor's grandsons, met with Pedro II and tried to convince him to join their cause.

[115] There he received Louis Pasteur, Ambroise Thomas, Pierre Émile Levasseur, François Coppée, Alexandre Dumas, fils, Arsène Houssaye, Guerra Junqueiro, and two of Victor Hugo's grandsons, among others.

"[131][137][138] Such popular enthusiasm directed toward the Emperor was not matched even by the celebrations of his majority in 1840, in the Christie Affair of 1864, upon his departure to Rio Grande do Sul in 1865, or even after the victory in the Paraguayan War in 1870.

[137][139] "To judge from the general manifestations of affection that the Emperor and the Empress had received on the occasion of their arrival from Europe, in this winter of 1888, no political institution seemed to be so strong as the monarchy in Brazil.

[142] Along with the successful appearances made by Eu and Isabel in São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul provinces from November 1884 to March 1885,[144] there was every indication of broad backing for the monarchy among the Brazilian population.

[11] Predictions of economic and labor disruption caused by the abolition of slavery failed to materialize and the 1888 coffee harvest was successful, both of which boosted Princess Isabel's popularity.

[149] Among the reforms proposed were the expanding of voting rights by abolishing the income requisite, the end of lifelong senate tenures and, most important of all, increased decentralization which would turn the country into a full federation by allowing the election of town mayors and provincial presidents (governors).

[154] As the Count of Nioac, a noted politician, remarked: "I call your attention especially to the reorganization of the National Guard, in order to possess this force with which in past times the government suppressed military revolts.

[157] The reorganization of the National Guard was begun by the cabinet in August 1889, and the creation of a rival militia caused the dissidents among the officer corps to consider desperate steps.

[160] Two days later in the house of Rui Barbosa a plan to execute the coup was drawn up by officers who included Benjamin Constant and Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca, plus two civilians: Quintino Bocaiuva and Aristides Lobo.

[164] Floriano and the Minister of the War Rufino Enéias, Viscount of Maracajú (a cousin of Deodoro) ignored repeated orders from Ouro Preto to attack the rebels who were approaching the headquarters.

[167][172] At 11 a.m. as he left a mass in honor of the 45th anniversary of his sister Maria II's death, the monarch received a second telegram and decided to return to Rio de Janeiro.

"[211] Major Carlos Nunes de Aguiar later recalled saying to Rui Barbosa, who had been at his side witnessing the departure from afar: "You were right to weep when the Emperor left.