Degenerate conic

In geometry, a degenerate conic is a conic (a second-degree plane curve, defined by a polynomial equation of degree two) that fails to be an irreducible curve.

This means that the defining equation is factorable over the complex numbers (or more generally over an algebraically closed field) as the product of two linear polynomials.

Using the alternative definition of the conic as the intersection in three-dimensional space of a plane and a double cone, a conic is degenerate if the plane goes through the vertex of the cones.

For any degenerate conic in the real plane, one may choose f and g so that the given degenerate conic belongs to the pencil they determine.

, and corresponds to two intersecting lines forming an "X".

This degenerate conic occurs as the limit case

is an example of a degenerate conic consisting of twice the line at infinity.

Similarly, the conic section with equation

The conic consists thus of two complex conjugate lines that intersect in the unique real point,

Over the complex projective plane there are only two types of degenerate conics – two different lines, which necessarily intersect in one point, or one double line.

Over the real affine plane the situation is more complicated.

Non-degenerate real conics can be classified as ellipses, parabolas, or hyperbolas by the discriminant of the non-homogeneous form

This determinant is positive, zero, or negative as the conic is, respectively, an ellipse, a parabola, or a hyperbola.

Analogously, a conic can be classified as non-degenerate or degenerate according to the discriminant of the homogeneous quadratic form in

[1][2]: p.16 Here the affine form is homogenized to the discriminant of this form is the determinant of the matrix The conic is degenerate if and only if the determinant of this matrix equals zero.

[3]: p.108 Conics, also known as conic sections to emphasize their three-dimensional geometry, arise as the intersection of a plane with a cone.

Degeneracy occurs when the plane contains the apex of the cone or when the cone degenerates to a cylinder and the plane is parallel to the axis of the cylinder.

See Conic section#Degenerate cases for details.

Degenerate conics, as with degenerate algebraic varieties generally, arise as limits of non-degenerate conics, and are important in compactification of moduli spaces of curves.

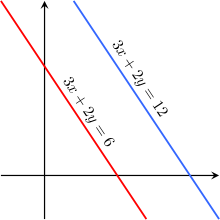

For example, the pencil of curves (1-dimensional linear system of conics) defined by

Such families arise naturally – given four points in general linear position (no three on a line), there is a pencil of conics through them (five points determine a conic, four points leave one parameter free), of which three are degenerate, each consisting of a pair of lines, corresponding to the

yielding the following pencil; in all cases the center is at the origin:[note 1] Note that this parametrization has a symmetry, where inverting the sign of a reverses x and y.

In the terminology of (Levy 1964), this is a Type I linear system of conics, and is animated in the linked video.

A striking application of such a family is in (Faucette 1996) which gives a geometric solution to a quartic equation by considering the pencil of conics through the four roots of the quartic, and identifying the three degenerate conics with the three roots of the resolvent cubic.

Pappus's hexagon theorem is the special case of Pascal's theorem, when a conic degenerates to two lines.

A general conic is defined by five points: given five points in general position, there is a unique conic passing through them.

If three of these points lie on a line, then the conic is reducible, and may or may not be unique.

If four points are collinear, however, then there is not a unique conic passing through them – one line passing through the four points, and the remaining line passes through the other point, but the angle is undefined, leaving 1 parameter free.

Given four points in general linear position (no three collinear; in particular, no two coincident), there are exactly three pairs of lines (degenerate conics) passing through them, which will in general be intersecting, unless the points form a trapezoid (one pair is parallel) or a parallelogram (two pairs are parallel).

Given two distinct points, there is a unique double line through them.