Delaware River Iron Ship Building and Engine Works

The yard specialized in the production of large passenger freighters, but built every kind of vessel from warships to cargo ships, oil tankers, ferries, barges, tugs and yachts.

It also established a reputation for itself as a builder of lavishly outfitted "night boats" for the Long Island Sound trade, and in its last years, built the first three American ships to be powered by steam turbines.

John Roach began his career in the United States in 1832 as a semi-literate Irish immigrant laborer, eventually establishing his own small business with the purchase of the Etna Iron Works.

[2] Roach had observed that the British were in the process of replacing their merchant fleet of dated wooden-hulled paddle steamers with modern iron-hulled, screw-propelled vessels, and he anticipated a similar trend in the United States.

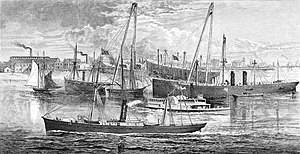

In June 1871, he bought the former Reaney shipyard from the receivers for the sum of $450,000, and renamed it the Delaware River Iron Ship Building and Engine Works.

The spacious 23-acre (93,000 m2) yard was ideally situated along a 1,200-foot (370 m) stretch of the Delaware where the river was over a mile wide and 18 feet (5.5 m) deep at the shore, allowing for launching of the largest vessels.

Like his early mentor James P. Allaire, Roach envisaged a vertically integrated shipbuilding empire stretching from control of the raw materials to the finished ships.

Collectively, the Roach, Houston and Crozer families employed 25% of Chester's working population and accounted for 35% of its payroll, their partnership virtually ensuring dominance of the city's politics.

's management experience was mostly in farming rather than shipbuilding however, Roach senior made a point of traveling from New York to Chester every Saturday, where he would conduct a thorough tour of every department, checking the workmanship, and ordering modifications and adjustments where required.

Criteria for payment included not only a worker's skill level, but his punctuality, dependability, eagerness and quality of work, in addition to which his moral character was subject to assessment.

Workers who spent too much on alcohol, who paid their rent erratically, whose families were poorly clothed, or whose children did not attend church or school, could expect to have their wages reduced still further.

[15][16] In 1872, the U.S. Congress awarded the Pacific Mail Steamship Company a $500,000 annual subsidy to operate a steam packet service between the United States and the Far East.

Pacific Mail thereupon decided to upgrade its entire fleet of aging, wood-hulled sidewheel steamers by replacing them with modern iron-hulled screw steamships.

To make matters worse, stock speculator Jay Gould, in an attempt to gain control of the company by driving down its share price, subsequently persuaded the U.S. Congress to rescind Pacific Mail's $500,000 subsidy.

He eventually built more ships for Pacific Mail, however, this early negative experience led him to reject future shipbuilding contracts sought on terms.

He was soon to discover that he had seriously underestimated the conservatism of American shipping lines, most of whom were content to continue ordering the familiar wooden-hulled paddle steamers in spite of the proven advantages of iron hulls and screw propulsion.

In order to attract more business, Roach tried reducing the entry cost of purchase by offering to buy shares in the ships he sold, taking a corresponding ratio of their future earnings as part payment for their construction.

Columbia was the first ship to utilize a dynamo and the first structure other than Thomas Edison's Menlo Park, New Jersey laboratory to use the incandescent light bulb.

A notable vessel built by the yard in this period was the "night boat" Pilgrim for the Fall River Line, which was fitted with the largest simple walking beam engine ever installed in a steamboat.

[29][30] Roach invited President Rutherford B. Hayes and the entire U.S. Congress to the launch of City of Para in 1878, but to his consternation, his attempts to secure subsidies from the U.S. and Brazilian governments were both to meet with failure.

[32][33] Roach lost almost a million dollars on the first Brazil Line alone, and the failed venture was to leave his shipyard chronically short of operating capital.

Roach was left with an unpaid $200,000 bill on Puritan, and was forced to keep the unfinished vessel in his shipyard at his own expense until 1882 when the government finally appropriated funds for its completion.

[44] The government issued public tenders for construction of the ships in June 1883, and on 3 July it was announced that John Roach & Sons had won all four contracts.

Fearing a public backlash from the bankruptcy of the nation's biggest shipyard, Secretary of the Navy William Whitney moved quickly to limit the political damage.

The last ship built by the Delaware River Works was fittingly a vessel for Ocean Steamship, the 5,600-ton passenger freighter City of Savannah, delivered in August 1907.

The Old Dominion Steamship Company, which had constructed SS George W. Elder in 1874 and Manhattan (1879), Breakwater (1880) then Guyandotte and Roanoke in 1882,[57] became a major client in the 1890s, ordering five passenger freighters of about 3,000 tons including Jamestown and Yorktown, built in 1894, Princess Anne (1897), and the sister ships Hamilton and Jefferson, completed in 1899.

The Line's steamboats—classic sidewheel steamers equipped with sleeping berths for overnight journeys (hence the term "night boat")—maintained a tradition of opulence that earned them the title of "floating palaces".

As with the Fall River Line night boats, these vessels were contracted for by W. & A. Fletcher Co., which built the ships' engines and subcontracted with the Roach yard for construction of the hulls.

Governor Cobb, a 2,700 ton passenger steamer built in 1906 for the Boston-New Brunswick trade, has the double distinction of being not only America's first turbine-powered vessel, but also of eventually becoming the world's first helicopter carrier.

The 3,750-ton sister ships Yale and Harvard—built in 1907 for the Metropolitan Steamship Company, which operated them between New York and Boston—had a top speed of 23 knots (43 km/h) and when first entering service were the fastest American-flagged vessels afloat.