Depiction of Jesus

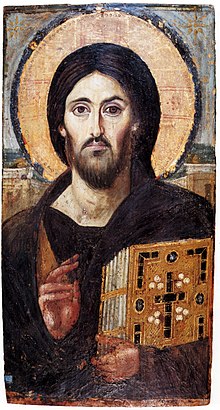

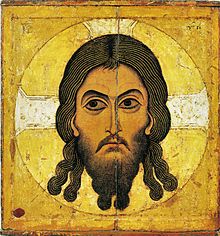

The conventional image of a fully bearded Jesus with long hair emerged around AD 300, but did not become established until the 6th century in Eastern Christianity, and much later in the West.

Beliefs that certain images are historically authentic, or have acquired an authoritative status from Church tradition, remain powerful among some of the faithful, in Eastern Orthodoxy, Lutheranism, Anglicanism, and Roman Catholicism.

[not verified in body] The representation of Jesus was controversial in the early period; the regional Synod of Elvira in Spain in 306 states in its 36th canon that no images should be in churches.

In the Book of Revelation there is a vision the author had of "someone like a Son of Man" in spirit form: "dressed in a robe reaching down to his feet and with a golden sash around his chest.

In the first-century AD, many Jews understood Exodus 20:4–6 ("Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image") as a proscription against any depiction of humans or animals.

[citation needed] The 36th canon of the non-ecumenical Synod of Elvira in 306 AD reads, "It has been decreed that no pictures be had in the churches, and that which is worshipped or adored be not painted on the walls",[14] which has been interpreted by John Calvin and other Protestants as an interdiction of the making of images of Christ.

Later personified symbols were used, including Jonah, whose three days in the belly of the whale pre-figured the interval between Christ's death and resurrection; Daniel in the lion's den; or Orpheus charming the animals.

[21] Among the earliest depictions clearly intended to directly represent Jesus himself are many showing him as a baby, usually held by his mother, especially in the Adoration of the Magi, seen as the first theophany, or display of the incarnate Christ to the world at large.

He is depicted with close-cropped hair and wearing a tunic and pallium—the common male dress for much of Greco-Roman society, and similar to that found in the figure art in the Dura-Europos Synagogue.

Other scenes remain ambiguous—an agape feast may be intended as a Last Supper, but before the development of a recognised physical appearance for Christ, and attributes such as the halo, it is impossible to tell, as tituli or captions are rarely used.

During the 4th century a much greater number of scenes came to be depicted,[31] usually showing Christ as youthful, beardless and with short hair that does not reach his shoulders, although there is considerable variation.

[39] This depiction has been said to draw variously on Imperial imagery, the type of the classical philosopher,[40] and that of Zeus, leader of the Greek gods, or Jupiter, his Roman equivalent,[41] and the protector of Rome.

[44] The tendency of older scholars such as Talbot Rice to see the beardless Jesus as associated with a "classical" artistic style and the bearded one as representing an "Eastern" one drawing from ancient Syria, Mesopotamia and Persia seems impossible to sustain, and does not feature in more recent analyses.

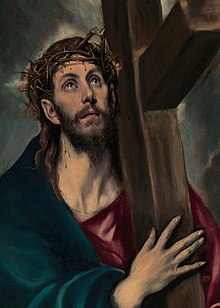

[49] Gradually Jesus became shown as older, and during the 5th century the image with a beard and long hair, now with a cruciform halo, came to dominate, especially in the Eastern Empire.

In the earliest large New Testament mosaic cycle, in Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna (c. 520), Jesus is beardless through the period of his ministry until the scenes of the Passion, after which he is shown with a beard.

But by the late Middle Ages the beard became almost universal and when Michelangelo showed a clean-shaven Apollo-like Christ in his Last Judgment fresco in the Sistine Chapel (1534–41) he came under persistent attack in the Counter-Reformation climate of Rome for this, as well as other things.

The depiction with a longish face, long straight brown hair parted in the middle, and almond shaped eyes shows consistency from the 6th century to the present.

[62][64][65][66] After Giotto, Fra Angelico and others systematically developed uncluttered images that focused on the depiction of Jesus with an ideal human beauty, in works like Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, arguably the first High Renaissance painting.

However Michelangelo was considered to have gone much too far in his beardless Christ in his The Last Judgment fresco in the Sistine Chapel, which very clearly adapted classical sculptures of Apollo, and this path was rarely followed by other artists.

The High Renaissance was contemporary with the start of the Protestant Reformation which, especially in its first decades, violently objected to almost all public religious images as idolatrous, and vast numbers were destroyed.

Meanwhile, the Catholic Counter-Reformation re-affirmed the importance of art in assisting the devotions of the faithful, and encouraged the production of new images of or including Jesus in enormous numbers, also continuing to use the standard depiction.

Although some scholars believed that Jesus wore long hair because he was a Nazarite and therefore could not cut his hair, Browne argues "that our Saviour was a Nazarite after this kind, we have no reason to determine; for he drank Wine, and was therefore called by the Pharisees, a Wine-bibber; he approached also the dead, as when he raised from death Lazarus, and the daughter of Jairus.”[69] By the end of the 19th century, new reports of miraculous images of Jesus had appeared and continue to receive significant attention, e.g. Secondo Pia's 1898 photograph of the Shroud of Turin, one of the most controversial artifacts in history, which during its May 2010 exposition it was visited by over 2 million people.

[77] A scene from the documentary film Super Size Me showed American children being unable to identify a common depiction of Jesus, despite recognizing other figures like George Washington and Ronald McDonald.

[citation needed] In modern times such variation has become more common, but images following the traditional depiction in both physical appearance and clothing are still dominant, perhaps surprisingly so.

In Europe, local ethnic tendencies in depictions of Jesus can be seen, for example in Spanish, German, or Early Netherlandish painting, but almost always surrounding figures are still more strongly characterised.

For example, the Virgin Mary, after the vision reported by Bridget of Sweden, was often shown with blonde hair, but Christ's is very rarely paler than a light brown.

[79] In 2001, the television series Son of God used one of three first-century Jewish skulls from a leading department of forensic science in Israel to depict Jesus in a new way.

[82] Additional information about Jesus' skin color and hair was provided by Mark Goodacre, a New Testament scholar and professor at Duke University.

"[94] The Head of Christ is venerated in the Coptic Orthodox Church,[95] after twelve-year-old Isaac Ayoub, who diagnosed with cancer, saw the eyes of Jesus in the painting shedding tears; Fr.

[96] In addition, several religious magazines have explained the "power of Sallman's picture" by documenting occurrences such as headhunters letting go of a businessman and fleeing after seeing the image, a "thief who aborted his misdeed when he saw the Head of Christ on a living room wall", and deathbed conversions of non-believers to Christianity.