Detachment fold

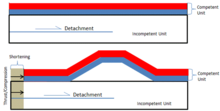

A detachment fold, in geology, occurs as layer parallel thrusting along a decollement (or detachment) develops without upward propagation of a fault; the accommodation of the strain produced by continued displacement along the underlying thrust results in the folding of the overlying rock units.

Two ways to maintain volume conservation are thickening of units and synclinal deflection of incompetent material; it is likely that both may occur.

[3] The occupancy of this area causes displacement above the detachment in the form of material migration to the anticlinal core.

Though many models have been developed to help explain the kinematic evolution of single layer detachment faulting;[7][9][10][11][12] many models do not account for multiple layers, complex fold geometries[12] or differential strain through fold geometries or mechanically dissimilar stratigraphic units.

The evolution of detachment folding begins with the model assumption of a low-amplitude and short compressional environment with a mechanically dissimilar incompetent and competent unit.

Folding initiates by shortening; limb lengthening and rotation and hinge migration, cause synclinal deflection below its original position accompanied by the flow of ductile material beneath the synclinal trough to the anticlinal core; resulting in increased amplitude of the anticlinal fold.

Through further deformation by limb rotation and through hinge migration, isoclinal folds eventually assume lift-off geometries.

Refer to Mitra[4][15] for an evolutionary model of faulted detachment folds in the asymmetric and symmetric settings.

Faulting in either setting is reliant on the lock-up and strain accumulation of a fold typically at its critical angle.

It is also the case that a backthrust may occur in an asymmetric fold geometry as shear across the forelimb due to rotation and migration of beds.