Determiner phrase

[2] The DP analysis developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s,[3] and it is the majority view in generative grammar today.

Noam Chomsky, on whose framework most generative grammar has been built, said in a 2020 lecture, I’m going to assume here that nominal phrases are actually NPs.

The DP hypothesis, which is widely accepted, was very fruitful, leading to a lot of interesting work; but I’ve never really been convinced by it.

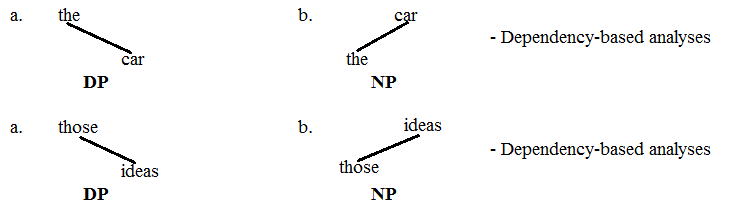

The point is illustrated with simple dependency-based hierarchies: Only the DP-analysis shown in c establishes the parallelism with the verb chain.

The fact that determiners typically introduce the phrases in which they appear is also viewed as support for the DP-analysis.

The fact that definite pronouns are in complementary distribution with determiners is taken as evidence in favor of DP.

In other words, the NP-analysis has to reach to additional stipulations to account for the fact that combinations like *the them are impossible.

While the DP-hypothesis has largely replaced the traditional NP analysis in generative grammar, it is generally not held among advocates of other frameworks, for six reasons:[9] 1) absent determiners, 2) morphological dependencies, 3) semantic and syntactic parallelism, 4) idiomatic expressions, 5) left-branch phenomena, and 6) genitives.

In other words, the DP-analysis must posit the frequent occurrence of null determiners in order to remain consistent about its analysis of DPs.

Thus the traditional NP analysis requires less of the theoretical apparatus, since it does not need all those null determiners, the existence of which is non-falsifiable.

Semantic and grammatical features of the noun influence the choice and morphological form of the determiner, not vice versa.

In English, this state of affairs is visible in the area of grammatical number, for instance with the opposition between singular this and that and plural these and those.

The DP-analysis, in contrast, is unintuitive because it necessitates that one view the dependent noun as influencing the choice and form of the head determiner.

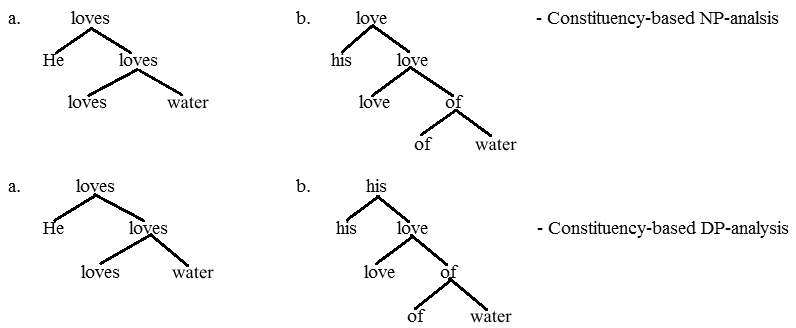

The same point is true for a constituency-based analysis: These trees again employ the convention whereby the words themselves are used as the node labels.

In contrast, the DP analysis destroys this parallelism because his no longer appears as a specifier in the NP, but rather as head over the noun.

This fact is a problem for the DP-analysis because it means that the fixed words of the idiom are interrupted in the vertical dimension.

The point is clearly visible in dependency-based structures: The arrangement of the words in the vertical dimension is what is important.

The NP-analysis is consistent with this observation because it positions both attributive adjectives and determiners as left-branch dependents of nouns.

In other words, the traditional NP-analysis is consistent with the fact that determiners behave just like attributive adjectives with respect to long-distance dependencies, whereas the DP-analysis cannot appeal to left branches to account for this behavior because on the DP-analysis, the determiner is no longer on a left branch underneath the noun.

The NP-analysis is consistent with the observation that genitive case in languages like German can have the option to appear before or after the noun, whereby the meaning remains largely the same, as illustrated with the following examples: While the b-phrases are somewhat archaic, they still occur on occasion in elevated registers.

The fact that the genitive NPs meines Bruders and seines Onkels can precede or follow the noun is telling, since it suggests that the hierarchical analysis of the two variants should be similar in a way that accommodates the almost synonymous meanings.

The DP-analysis, in contrast, is challenged because in the b-variants, it takes the genitive expression to be head over the noun.

In other words, the DP-analysis has to account for the fact that the meaning remains consistent despite the quite different structures across the two variants.