Development of Doom

The initial months of development were spent building prototypes, while Hall created the Doom Bible, a design document for his vision of the game and its story; after id released a grandiose press release touting features that the team had not yet begun working on, the Doom Bible was rejected in favor of a plotless game with no design document at all.

It is often referred to as the "grandfather" of first-person shooters,[4][5] setting expectations for fast-paced action and new technology, and greatly increased the genre's popularity.

They collectively felt that the platforming gameplay of the series was a poor fit for Carmack's fast-paced 3D engines, and especially after the success of Wolfenstein were interested in pursuing more games of that type.

John Carmack soon lost interest in Keen idea as well, instead coming up with his own concept: a game about using technology to fight demons, inspired by the Dungeons & Dragons campaigns the team played, combining the styles of Evil Dead II and Aliens.

Rather than a deep story, John Carmack wanted to focus on the technological innovations, dropping the levels and episodes of Wolfenstein in favor of a fast, continuous world.

[14] Hall spent the next few weeks reworking the Doom Bible to work with Carmack's technological ideas, while the rest of the team planned how they could implement them.

[10] His adjusted vision for the plot had the player character assigned to a large military base on an alien planet, Tei Tenga.

He envisioned a six episode structure with a storyline involving traveling to Hell and back through the gates which the demons used, and the destruction of the planet, for which the players would be sent to jail.

[14][15] Buddy was named after Hall's character in a Dungeons & Dragons campaign run by John Carmack that had featured a demonic invasion.

[14] Hall was forced to rework the Doom Bible again in December, however, after John Carmack and the rest of the team had decided that they were unable to create a single, seamless world with the hardware limitations of the time, which contradicted much of the new document.

[12] Other elements, such as a complex user interface, an inventory system, a secondary shield protection, and lives were modified and slowly removed over the course of development.

[10][18] Soon, however, the Doom Bible as a whole was rejected: Romero wanted a game even "more brutal and fast" than Wolfenstein, which did not leave room for the character-driven plot Hall had created.

[14] Additionally, the team did not feel that they needed a design document at all, as they had not created one for prior games; the Doom Bible was discarded altogether.

[14] Several ideas were retained, including starting off in a military base, as well as some locations, items, and monsters, but the story was dropped and most of the design was removed as the team felt it emphasized realism over entertaining gameplay.

[14] Hall was replaced in September, ten weeks before Doom was released, by game designer Sandy Petersen, despite misgivings over his relatively high age of 37 compared to the other early-20s employees and his religious background.

[21][22] Petersen later recalled that John Carmack and Romero wanted to hire other artists instead, but Cloud and Adrian disagreed, saying that a designer was required to help build a cohesive gameplay experience.

[17] In late 1993, a month before release, John Carmack began to add multiplayer to the game, first teaching himself computer networking from a book.

The team frequently played Street Fighter II, Fatal Fury and Art of Fighting during breaks, while developing elaborate rules involving trash-talk and smashing furniture or equipment.

Carmack had been impressed by the modifications made by fans of Wolfenstein 3D, and wanted to support that with an easily swappable file structure, and released the map editor online.

The fading visibility in ShadowCaster was improved by adjusting the color palette by distance, darkening far surfaces and creating a grimmer, more realistic appearance.

[10][24] Taylor, along with programming other features, added cheat codes; some, such as "idspispopd", were based on ideas their fans had come up with while eagerly awaiting the game that the team found amusing.

John Carmack began to work on the multiplayer component; within two weeks he had two computers playing the same game over the internal office network.

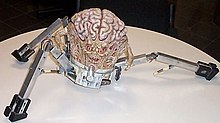

[29] Unlike Wolfenstein, where Carmack had drawn every frame of animation for the Nazi enemy sprites, for Doom the artists sculpted models of some of the enemies out of clay, and took pictures of them in stop motion from five to eight different angles so that they could be rotated realistically in-game; the images were then digitized and converted to 2D characters with a program written by John Carmack.

[22][35] Id Software planned to self-publish the game for DOS-based computers and set up a distribution system leading up to the release.

He felt that the mainstream press was uninterested, and as id would make the most money off of copies they sold directly to customers—up to 85 percent of the planned US$40 price—he decided to leverage the shareware market as much as possible, buying only a single ad in any gaming magazine.

Id began receiving calls from people interested in the game or angry that it had missed its planned release date, as anticipation built over the year.

At midnight on Friday, December 10, 1993, after working for 30 straight hours testing the game, the team uploaded the first episode to the internet, letting interested players distribute it for them.