Spanish dialects and varieties

The Spanish spoken in Gibraltar is essentially not different from the neighboring areas in Spain, except for code-switching with English and some unique vocabulary items.

In the area around the Río de la Plata (Argentina, Uruguay), this phoneme is pronounced as a palatoalveolar sibilant fricative, either as voiced [ʒ] or, especially by young speakers, as voiceless [ʃ].

In northern and central Spain, and in the Paisa Region of Colombia, as well as in some other, isolated dialects (e.g. some inland areas of Peru and Bolivia), the sibilant realization of /s/ is an apico-alveolar retracted fricative [s̺], a sound transitional between laminodental [s] and palatal [ʃ].

Some efforts to explain this vowel reduction link it to the strong influence of Nahuatl and other Native American languages in Mexican Spanish.

In much of Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela (except for the Andean region) and Dominican Spanish, any pre-consonantal nasal can be realized [ŋ]; thus, a word like ambientación can be pronounced [aŋbjeŋtaˈsjoŋ].

The single-R phoneme corresponds to the letter r written once (except when word-initial or following l, n, or s) and is pronounced as [ɾ], an alveolar flap—like American English tt in better—in virtually all dialects.

[18] The double-R phoneme is spelled rr between vowels (as in carro 'car') and r word-initially (e.g. rey 'king', ropa 'clothes') or following l, n, or s (e.g. alrededor 'around', enriquecer 'enrich', enrollar 'roll up', enrolar 'enroll', honra 'honor', Conrado 'Conrad', Israel 'Israel').

The trill is also found in lexical derivations (morpheme-initial positions), and prefixation with sub and ab: abrogado [aβroˈɣa(ð)o], 'abrogated', subrayar [suβraˈʝar], 'to underline'.

However, after vowels, the initial r of the root becomes rr in prefixed or compound words: prorrogar, infrarrojo, autorretrato, arriesgar, puertorriqueño, Monterrey.

[25][26] The pronunciation of the double-R phoneme as a voiced strident (or sibilant) apical fricative is common in New Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, and Paraguay; in western and northern Argentina; and among older speakers in highland areas of Colombia.

[30] These realizations for rr maintain their contrast with the phoneme /x/, as the latter tends to be realized as a soft glottal [h]: compare Ramón [xaˈmoŋ] ~ [ʀ̥aˈmoŋ] ('Raymond') with jamón [haˈmoŋ] ('ham').

/tl/ is a valid onset cluster in Latin America, with the exception of Puerto Rico, in the Canary Islands, and in the northwest of Spain, including Bilbao and Galicia.

In those countries, it is used by many to address others in all kinds of contexts, often regardless of social status or age, including by cultured/educated speakers and writers, in television, advertisements, and even in translations from other languages.

Based on these factors, speakers can assess themselves as being equal, superior, or inferior to the addressee, and the choice of pronoun is made on this basis, sometimes resulting in a three-tiered system.

On the other hand, "pronominal voseo", the use of the pronoun vos—pronounced with aspiration of the final /s/—is used derisively in informal speech between close friends as playful banter (usually among men) or, depending on the tone of voice, as an offensive comment.

A peculiarity occurs in the Altiplano Cundiboyacense and among some speakers in Bogotá: usted is replaced by sumercé for formal situations (it is relatively easy to identify a Boyacense by his/her use of this pronoun).

[49][50] A slightly different explanation is that in Spain, even if vos (as a singular) originally denoted the high social status of those who were addressed as such (monarchs, nobility, etc.

This assumption, however, has been challenged, in an article by Baquero & Westphal (2014)—in the theoretical framework of classical generative phonology—as synchronically inadequate, on the grounds that it requires at least six different rules, including three monophthongization processes that lack phonological motivation.

Alternatively, the article argues that the Chilean and River Plate voseo verb forms are synchronically derived from underlying representations that coincide with those corresponding to the non-honorific second person singular tú.

The article additionally solves the problem posed by the alternate verb forms of Chilean voseo such as the future indicative (e.g. vay a bailar 'will you dance?

The only vestiges of vosotros in the Americas are boso/bosonan in Papiamento and the use of vuestro/a in place of sus (de ustedes) as second person plural possessive in the Cusco region of Peru.

General statements about the use of voseo in different localities should be qualified by the note that individual speakers may be inconsistent in their usage, and that isoglosses rarely coincide with national borders.

The choice between preterite and perfect, according to prescriptive grammars from both Spain[53][54] and the Americas,[55] is based on the psychological time frame—whether expressed or merely implied—in which the past action is embedded.

But if the time frame does not include the present—if the speaker views the action as only in the past, with little or no relation to the moment of speaking—then the recommended tense is the preterite (llegué).

Meanwhile, in Galicia, León, Asturias, Canary Islands and the Americas, speakers follow the opposite tendency, using the simple past tense in most cases, even if the action takes place at some time close to the present: In Latin America one could say, "he viajado a España varias veces" ('I have traveled to Spain several times'), to express a repeated action, as in English.

In Spain, speakers use the compound tense when the period of time considered has not ended, as in he comprado un coche este año ('I have bought a car this year').

Exceptionally, the made-in-Spain animated features Dogtanian and the Three Muskehounds and The World of David the Gnome, as well as TV serials from the Andean countries such as Karkú (Chile), have had a Mexican dub.

This standard tends to disregard local grammatical, phonetic and lexical peculiarities, and draws certain extra features from the commonly acknowledged canon, preserving (for example) certain verb tenses considered "bookish" or archaic in most other dialects.

Mutual intelligibility in Spanish does not necessarily mean a translation is wholly applicable in all Spanish-speaking countries, especially when conducting health research that requires precision.

For example, an assessment of the applicability of QWB-SA's Spanish version in Spain showed that some translated terms and usage applied US-specific concepts and regional lexical choices and cannot be successfully implemented without adaptation.

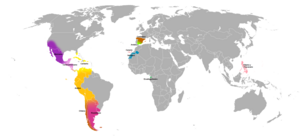

In other colors, the extent of the other languages of Spain in the bilingual areas.