Die casting

Most die castings are made from non-ferrous metals, specifically zinc, copper, aluminium, magnesium, lead, pewter, and tin-based alloys.

The casting equipment and the metal dies represent large capital costs and this tends to limit the process to high-volume production.

Manufacture of parts using die casting is relatively simple, involving only four main steps, which keeps the incremental cost per item low.

Die casting equipment was invented in 1838 for the purpose of producing movable type for the printing industry.

The first die casting-related patent was granted in 1849 for a small hand-operated machine for the purpose of mechanized printing type production.

[2] Other applications grew rapidly, with die casting facilitating the growth of consumer goods, and appliances, by greatly reducing the production cost of intricate parts in high volumes.

[9] By late-2019, press machines capable of die casting single pieces over-100 kilograms (220 lb) were being used to produce aluminium chassis components for cars.

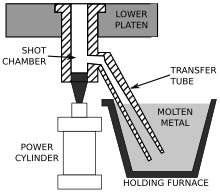

At the beginning of the cycle the piston of the machine is retracted, which allows the molten metal to fill the "gooseneck".

The disadvantages of this system are that it is limited to use with low-melting point metals and that aluminium cannot be used because it picks up some of the iron while in the molten pool.

[15] Then a precise amount of molten metal is transported to the cold-chamber machine where it is fed into an unheated shot chamber (or injection cylinder).

The biggest disadvantage of this system is the slower cycle time due to the need to transfer the molten metal from the furnace to the cold-chamber machine.

Heat checking is when surface cracks occur on the die due to a large temperature change on every cycle.

Thermal fatigue is when surface cracks occur on the die due to a large number of cycles.

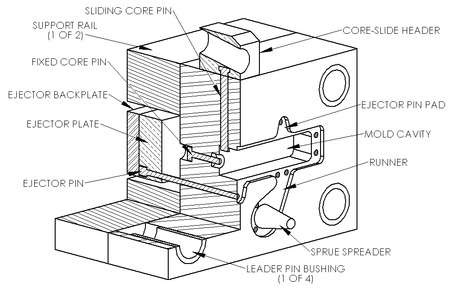

Finally, the shakeout involves separating the scrap, which includes the gate, runners, sprues and flash, from the shot.

This problem is minimized by including vents along the parting lines, however, even in a highly refined process there will still be some porosity in the center of the casting.

[23] Most die casters perform other secondary operations to produce features not readily castable, such as tapping a hole, polishing, plating, buffing, or painting.

Unlike solvent-based lubricants, if water is properly treated to remove all minerals from it, it will not leave any by-product in the dies.

Today "water-in-oil" and "oil-in-water" emulsions are used, because, when the lubricant is applied, the water cools the die surface by evaporating, hence depositing the oil that helps release the shot.

Other substances are added to control the viscosity and thermal properties of these emulsions, e.g. graphite, aluminium, mica.

In addition emulsifiers are added to improve the emulsion manufacturing process, e.g. soap, alcohol esters, ethylene oxides.

These were good at releasing the part from the die, but a small explosion occurred during each shot, which led to a build-up of carbon on the mould cavity walls.

It was developed to combine a stable fill and directional solidification with the fast cycle times of the traditional die casting process.

It is identical to the standard process except oxygen is injected into the die before each shot to purge any air from the mould cavity.

This causes small dispersed oxides to form when the molten metal fills the die, which virtually eliminates gas porosity.

Vacuum die casting reduces porosity, allows heat treating and welding, improves surface finish, and can increase strength.

This process has the advantages of lower cost per part, through the reduction of scrap (by the elimination of sprues, gates, and runners) and energy conservation, and better surface quality through slower cooling cycles.

[citation needed] Low-pressure die casting (LPDC) is a process developed to improve the consistency and integrity of parts, at the cost of a much slower cycle time.

[34][35] Somewhat higher pressures (up to 1 bar (15 psi)) may be applied after the material is in the die, to work it into fine details of the cavity and eliminate porosity.

The aim is to reduce manufacturing costs through one-time molding, significantly decreasing the number of parts needed for car assembly and improving overall efficiency.