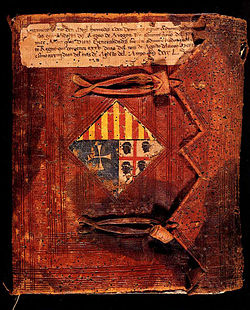

Diputación del General del Reino de Aragón

However, the institution soon became a key body for the management of the resources dedicated to the defense of the Kingdom, with administrative, political, military and representative attributions of the power emanating from the Cortes by delegation.

In its noble hall there was a gallery with the paintings of all the kings of Aragon and it housed the Archive of the Kingdom, which was partially destroyed after a dreadful three-day fire during the Sieges of Zaragoza, along with a large part of the palace.

So much so, that in the Cortes of Alcañiz of 1436 gathered by Alfonse V to ask for help in the delicate situation in Italy, he had to cede to the Diputación the representation of the Kingdom and the capacity to intervene in political matters of the utmost importance.

Then, the innocent hand of a ten-year-old child proceeded to extract a wax ball or redolino containing the name of the elected representative, making a total of eight deputies whose mandate was annual.

In the second half of the 15th century, and until the reign of Ferdinand II of Aragon, the Diputación del Reino was responsible for maintaining order, settling disputes between the different estates and controlling the institution of Justicia by appointing his lieutenants.

In this way they became an element of independence from the Crown that was respected until the economic and political needs of the expansion of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries forced the king to intervene directly in the decisions of the Kingdom and finally impose his authority over its institutions.

In addition, and although he could not introduce the figure of the corregidor as was done in Castile, he reduced the independence of the branch of the universities by appointing the list of candidates according to the loyalty to his person, who, on the other hand, reserved the possibility of ordering the revision of the elective procedure.

[3] All these measures were effective instruments of consolidation of the royal command to the detriment of the Diputación, although both the institution and the Cortes maintained their privileges without Ferdinand the Catholic undertaking any structural reform, which would not occur until 1592, after the outbreak of the conflict of powers with Philip II.

In addition, on February 8, 1592, the king suppressed the powers of the Diputación in matters of Defense and Guarda del Reino, which ensured the security of trade routes and border control.

He also ordered the seizure of the acts of the Diputación and demanded reparations consisting of returning the income used in the call to raise an Aragonese army that could oppose the imperial troops, valued at 700,000 jaquesa pounds, an amount that left the kingdom in debt.

From now on, the Diputación del General would not be able to summon any city, village, or place in the Kingdom to meet (...) without the express wish of His Majesty, unless it is for matters concerning the Generalidades (...).That is, for the original function of administration of Hacienda for which the institution was created in the 14th century.

From then on, the Diputación was concerned with keeping alive the flame of the institutions and the existence of a ruling class in Aragon, manifested in an enormous work of legal and historical literature on the peculiarities of the region.

The urgency of the needs of the Imperium led the monarchy of Philip IV to bypass the foral procedures on numerous occasions without the Diputación being able to oppose due to the special war situation and the scarce power that the Aragonese institution could wield in the mid-17th century in the face of these outrages.

In 1693, after the invasion of Catalonia by the French army, the Deputation could not even gather a third of combat of 600 infantrymen, which was less than two hundred men, so Charles II asked for an effort to Branch of the Universities, that is to say, to cities, towns and communities, to complete the third with the contribution of an armed man for every fifty neighbors, without being able to be carried out given the state of prostration to which the Aragonese populations had arrived at the end of the 17th century.

In 1698, the Consistorio, having exhausted all its resources, wrote to the king: that this year being the Kingdom, due to the calamity of the times, with extreme sterility of all kinds of fruits, the ports, Universities and individuals are unable to make new contributions, and moreover, the voluntary donations of these years having been so repeated that some Universities have contracted new obligations because of them, which have yet to be paid.After the power of the institution had languished, exanimated before the effort demanded by the constraints of the politics of the last Austrias, the institution would see its definitive end when it aligned itself during the War of the Spanish Succession with the pretension to the throne of Archduke of Austria, crowned as Charles III in June 1706 in Madrid.

On the last day of that month all the deputies proclaimed Charles as king of Aragon in a solemn public act, with the only opposition of Miguel de Sada y Antillón, who fled to the Kingdom of Navarre, bastion of the House of Bourbon.

After the Bourbon reform, the collection functions of the extinct Diputación were taken over by the Junta del Real Erario, composed of two representatives from each of the former estates of ecclesiastics, nobles and universities (citizens).

At the beginning of 1808, in a reaction of a foral character against the Napoleonic invasion, the Cortes were reinstituted for a short time, which in turn created a Junta (with similar attributions to the Diputación) composed of three members from each of the traditional branches.