Dire wolf

This range restriction is thought to be due to temperature, prey, or habitat limitations imposed by proximity to the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets that existed at the time.

Its skull and dentition matched those of C. lupus, but its teeth were larger with greater shearing ability, and its bite force at the canine tooth was stronger than any known Canis species.

In 1857, while exploring the Niobrara River valley in Nebraska, Leidy found the vertebrae of an extinct Canis species that he reported the following year under the name C. dirus.

[6] In 1908 the paleontologist John Campbell Merriam began retrieving numerous fossilized bone fragments of a large wolf from the Rancho La Brea tar pits.

[26] The second theory is based on DNA evidence, which indicates that the dire wolf arose from an ancestral lineage that originated in the Americas and was separate from the genus Canis.

[28] The first appearance of C. dirus would therefore be 250,000 YBP in California and Nebraska, and later in the rest of the United States, Canada, Mexico, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru,[39] but the identity of these earliest fossils is not confirmed.

The sequences indicate the dire wolf to be a highly divergent lineage which last shared a most recent common ancestor with the wolf-like canines 5.7 million years ago.

Members of the wolf-like canines are known to hybridize with each other but the study could find no indication of genetic admixture from the five dire wolf samples with extant North American gray wolves and coyotes nor their common ancestor.

Coyotes, dholes, gray wolves, and the extinct Xenocyon evolved in Eurasia and expanded into North America relatively recently during the Late Pleistocene, therefore there was no admixture with the dire wolf.

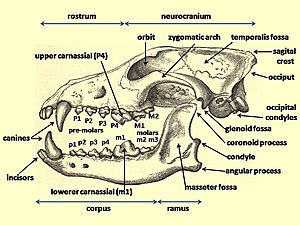

The skull length could reach up to 310 mm (12 in) or longer, with a broader palate, frontal region, and zygomatic arches compared with the Yukon wolf.

Its sagittal crest was higher, with the inion showing a significant backward projection, and with the rear ends of the nasal bones extending relatively far back into the skull.

A connected skeleton of a dire wolf from Rancho La Brea is difficult to find because the tar allows the bones to disassemble in many directions.

[20] The remains of a complete male A. dirus are sometimes easy to identify compared to other Canis specimens because the baculum (penis bone) of the dire wolf is very different from that of all other living canids.

These plant communities suggest a winter rainfall similar to that of modern coastal southern California, but the presence of coast redwood now found 600 kilometres (370 mi) to the north indicates a cooler, moister, and less seasonal climate than today.

Commencing 40,000 YBP, trapped asphalt has been moved through fissures to the surface by methane pressure, forming seeps that can cover several square meters and be 9–11 m (30–36 ft) deep.

Isotope analysis of bone collagen extracted from La Brea specimens provides evidence that the dire wolf, Smilodon, and the American lion (Panthera atrox) competed for the same prey.

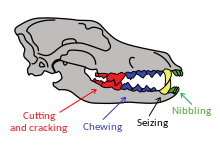

[79] When compared with the dentition of genus Canis members, the dire wolf was considered the most evolutionary derived (advanced) wolf-like species in the Americas.

"[30] A study of the estimated bite force at the canine teeth of a large sample of living and fossil mammalian predators, when adjusted for the body mass, found that for placental mammals the bite force at the canines (in newtons/kilogram of body weight) was greatest in the dire wolf (163), followed among the modern canids by the four hypercarnivores that often prey on animals larger than themselves: the African hunting dog (142), the gray wolf (136), the dhole (112), and the dingo (108).

[44] During the Last Glacial Maximum, coastal California, with a climate slightly cooler and wetter than today, is thought to have been a refuge,[75] and a comparison of the frequency of dire wolves and other predator remains at La Brea to other parts of California and North America indicates significantly greater abundances; therefore, the higher dire wolf numbers in the La Brea region did not reflect the wider area.

[85][86][87] To kill ungulates larger than themselves, the African wild dog, the dhole, and the gray wolf depend on their jaws as they cannot use their forelimbs to grapple with prey, and they work together as a pack consisting of an alpha pair and their offspring from the current and previous years.

[20][86][87] Stable isotope analysis of dire wolf bones provides evidence that they had a preference for consuming ruminants such as bison rather than other herbivores but moved to other prey when food became scarce, and occasionally scavenged on beached whales along the Pacific coast when available.

[92] A study of the fossil remains of large carnivores from La Brea pits dated 36,000–10,000 YBP shows tooth breakage rates of 5–17% for the dire wolf, coyote, American lion, and Smilodon, compared to 0.5–2.7% for ten modern predators.

The dorsoventrally weak symphyseal region (in comparison to premolars P3 and P4) of the dire wolf indicates that it delivered shallow bites similar to its modern relatives and was therefore a pack hunter.

[70] Nutrient stress is likely to lead to stronger bite forces to more fully consume carcasses and to crack bones,[70][98] and with changes to skull shape to improve mechanical advantage.

North American climate records reveal cyclic fluctuations during the glacial period that included rapid warming followed by gradual cooling, called Dansgaard–Oeschger events.

[96] Specimens that have been identified by morphology as Beringian wolves (C. lupus) and radiocarbon dated 25,800–14,300 YBP have been found in the Natural Trap Cave at the base of the Bighorn Mountains in Wyoming, in the western United States.

A temporary channel between the glaciers may have existed that allowed these large, Alaskan direct competitors of the dire wolf, which were also adapted for preying on megafauna, to come south of the ice sheets.

[106][107][19][91] The cause of the extinction of the megafauna is debated[96] but has been attributed to the impact of climatic change, competition with other species including overexploitation by newly arrived human hunters, or a combination of both.

Gray wolves and coyotes may have survived due to their ability to hybridize with other canids – such as the domestic dog – to acquire traits that resist diseases brought by taxa arriving from Eurasia.

[21] A 2023 study documented a high degree of subchondral defects in joint surfaces of dire wolf and Smilodon specimens from the La Brea Tar pits that resembled osteochondrosis dissecans.