Discovery and development of direct thrombin inhibitors

Direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs) are a class of anticoagulant drugs that can be used to prevent and treat embolisms and blood clots caused by various diseases.

With technological advances in genetic engineering the production of recombinant hirudin was made possible which opened the door to this new group of drugs.

In 1884 John Berry Haycraft described a substance found in the saliva of leeches, Hirudo medicinalis, that had anticoagulant effects.

[2] In the early 20th century Jay McLean, L. Emmet Holt Jr. and William Henry Howell discovered the anticoagulant heparin, which they isolated from the liver (hepar).

[3] Heparin remains one of the most effective anticoagulants and is still used today, although it has its disadvantages, such as requiring intravenous administration and having a variable dose-response curve due to substantial protein binding.

[6] Warfarin has its disadvantages though, just like heparin, such as a narrow therapeutic index and multiple food and drug interactions and it requires routine anticoagulation monitoring and dose adjustment.

[4][7] Since both heparin and warfarin have their downsides the search for alternative anticoagulants has been ongoing and DTIs are proving to be worthy competitors.

[8] Furthermore, it activates factors V, VIII and XI, all by cleaving the sequences GlyGlyGlyValArg-GlyPro and PhePheSerAlaArg-GlyHis, selectively between Arginine (Arg) and Glycine (Gly).

Thrombin also activates factor XIII that stabilizes the fibrin complex and therefore the clot and it stimulates platelets, which help with the coagulation.

The surface in the gap seems to have limiting access to molecules by steric hindrance, this binding site consists of 3 amino acids, Asp-102, His-57 and Ser-195.

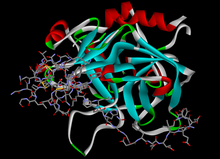

[9] Hirudin derivatives are all bivalent DTIs, they block both the active site and exosite 1 in an irreversible 1:1 stoichiometric complex.

It is an immune-mediated, prothrombotic complication which results from a platelet-activating immune response triggered by the interaction of heparin with platelet factor 4 (PF4).

[16] Three prospective studies, called the Heparin-Associated-Thrombocytopenia (HAT) 1,2, and 3, were performed that compared lepirudin with historical controls in the treatment of HIT.

[17] Desirudin is approved for treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe and multiple phase III trials are presently ongoing in the USA.

Different from the hirudins, once bound thrombin cleaves the Arg-Pro bond at the amino-terminal of bivalirudin and as a result restores the functions to the active site of the enzyme.

Even though the carboxy-terminal domain of bivalirudin is still bound to exosite 1 on thrombin, the affinity of the bond is decreased after the amino-terminal is released.

[10] The advantages of this type of DTIs are that they do not need monitoring, have a wide therapeutic index and the possibility of oral administration route.

[9] Dabigatran etexilate is rapidly absorbed, it lacks interaction with cytochrome P450 enzymes and with other food and drugs, there is no need for routine monitoring and it has a broad therapeutic index and a fixed-dose administration, which is excellent safety compared with warfarin.

[4] Unlike ximelagatran, a long-term treatment of dabigatran etexilate has not been linked with hepatic toxicity, seeing as how the drug is predominantly eliminated (>80%) by the kidneys.

Dabigatran etexilate was approved in Canada and Europe in 2008 for the prevention of VTE in patients undergoing hip- and knee surgery.

In October 2010 the US FDA approved dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

[6][10] Many pharmaceutical companies have attempted to develop orally bioavailable DTI drugs but dabigatran etexilate is the only one to reach the market.

[9] In a 2012 meta-analysis dabigatran was associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) or ACS when tested against different controls in a broad spectrum of patients.

[22] USA: FDA never gave approval[20] iv: intravenous, sc: subcutaneous, HIT: heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, VTE: Venous thromboembolism, DVT: Deep vein thrombosis, PTCA: Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, FDA: Food and Drug Administration, AF: Atrial fibrillation, TI: Therapeutic index In 2014 dabigatran remains the only approved oral DTI[9] and is therefore the only DTI alternative to the vitamin K antagonists.

Most of those drugs are in the class of direct factor Xa inhibitors, but there is one DTI called AZD0837,[26] which is a follow-up compound of ximelgatran that is being developed by AstraZeneca.

Due to a limitation identified in long-term stability of the extended-release AZD0837 drug product, a follow-up study from ASSURE on stroke prevention in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation, was prematurely closed in 2010 after 2 years.

[26] Another strategy for developing oral anticoagulant drugs is that of dual thrombin and fXa inhibitors that some pharmaceutical companies, including Boehringer Ingelheim, have reported on.