Divisome

[2] Some of the first cell-division genes of Escherichia coli were discovered by François Jacob's group in France in the 1960s.

[3] At the non-permissive temperature (usually 42 °C), fts mutant cells continue to elongate without dividing, forming filaments that can be up to 150

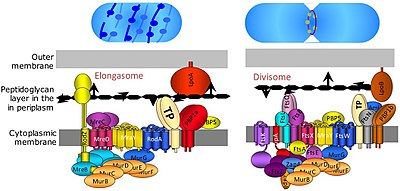

[7] Several other fts genes, such as ftsA, ftsW, ftsQ, ftsI, ftsL, ftsK, ftsN, and ftsB, were all found to be essential for cell division and to associate with the divisome complex and the FtsZ ring.

FtsA protein binds directly to FtsZ in the cytoplasm, and FtsB, FtsL and FtsQ form an essential membrane-embedded subcomplex.

[7] After the early proteins, the FtsQLB subcomplex is added,[9] followed by FtsI (transpeptidase), FtsW (transglycosylase), and FtsN.

[14] However, while FtsA, FtsQLB, FtsI and FtsW are widely conserved, FtsN is limited to Gram-negative organisms (such as E. coli) and hence is not universally required.

However, there seem to be some conserved aspects, e.g. in the red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae, a mitochondrial FtsZ protein partially constricts the organelle, which enables the dynamin homologue Dnm1 to assemble with the mitochondrion-dividing (MD) ring on the cytosolic face to induce fission.

However, in many eukaryotes (including yeasts and animals), the divisome functions in the complete absence of the contractile FtsZ ring.