Dominican Restoration War

With the best of intentions, Archbishop Bienvenido de Monzón wanted to rectify this situation within a short time, but his demands only irritated the local population, which had come to accept the current state of illegitimate births as normal.

[7]: 210–11 Since the end of 1862, the Spaniards sensed new possible anti-annexation uprisings; news had circulated of clandestine moments and meetings that showed the heated mood of the inhabitants of the Cibao region, as well as on the border with Haiti.

On August 25, the steam lsubelfl, captained by Commander Casto Méndez Núñez, set sail from the port of Santiago de Cuba with a contingent of 600 men destined to reinforce Puerto Plata.

Commander Mendez together to the head of the expeditionary column, Colonel Arizon, decided to disembark the battalion and the armed battery that came in the steam, in order to support the army besieged in the fort.

The number of rebels was large and, although poorly armed, they had managed to cut off all Spanish communications, making it impossible not only to exchange information, but also to harm the supply of the troops and the sending of the necessary military reinforcements.

The wounded and sick went on the rise and had to be taken to Cuba or Puerto Rico, alongside the rebel prisoners, delaying the distribution of men, provisions and ammunition, as well as the supply of coal from the same transport vessels.

When the governor of Cuba learned of the events in Puerto Plata, he immediately ordered the sending of 200,000 rations of food, ammunition, cannons and rifles for the troops and more than 100 mules for transportation and loading.

He ordered it without knowing for sure the true needs of the Spanish Army in Santo Domingo, doubting the solidity and continuity of the separatist actions and at the expense of the royal coffers of Cuba.

[13]: 18 Once the restorative government was established in Santiago, on September 14, 1863, the southern and eastern guerrilla centers had to be strengthened, but the patriots knew that they were at a disadvantage in terms of supplies and capacity in the face of the annexationist reinforcements that arrived from Cuba and Puerto Rico.

[23][18]But the restorers did not give up in their attempt, and repeatedly They sometimes carried out several attacks, but they were always repelled[24] since Samana was designated as the center of naval operations of the war, which caused that always was heavily armed and guarded.

Furthermore, San Cristobal was the crossroads that It communicated the Capital with the entire province of Azua, and was the shortest path that existed between Santo Domingo and Cibao, area of restorative operations.

It was necessary to adopt measures that allowed bacon to be alternated with beef and biscuits with fresh wheat bread, since the cookies get moldy with ease due to the high humidity of the island.

The Governor recommended That It was convenient that the force that came from the Peninsula arrived: ...provided with bell pots, mantles, backpacks with rubber covers and a master strap to hold the contents; lunch box, water jug with its corresponding belt, bags to carry stew, tubes for salt, two pairs of shoes per square and the same number of pairs of shoes; whose last garment it would be advisable to also bring a good replacement because in that island it is very difficult to acquire it and its quality is quite average.It was also recommended to provide jipijapa hats to protect the soldiers from the inclemencies of the sun.

So much so that a year before the hostilities ended and despite the fact that a powerful advance was ordered from Madrid To take the island north, the Spanish leaders began to consider withdrawal and peaceful negotiation with the restorers.

In addition, the Spanish Army and Navy began to provide poor troop mobilization and transportation services active, due to the lack of fuel and coal that since La Havana was not possible to send with the required regularity.

Trusting in a supposed good annexationist spirit that the Dominicans of San Francisco de Macoris, La Vega and Moca had, their plan consisted of organizing a joint operation, which, starting from Samana and Puerto Plata, would proceed to take the points occupied by the restaurateurs of Cibao.

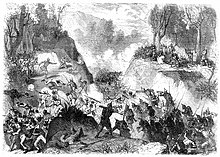

In evaluating the results of the campaign, and still intoxicated by the glories of triumph, General De la Gandara comments that: " (...) the material results of this operation consist of having remained in our power the town, the forts and the trenches of Monte Cristi, with thirteen pieces of artillery and having defeated an enemy that was believed to be impregnable in their truly advantageous positions; taking away the Port that was most important to them, and through which they received of his few hidden friends from Hayti and the Turks Islands most of the resources with which sustains the revolution.

I cannot judge the losses that the enemy has suffered, seven of our escaped prisoners who had employees in fortlJicaczon works they assure me that their dispersion and demoralization was complete, he had quite a few wounds, in addition to some dead people who were at the site of the combat...But the reality was different.

At the end of July, the commander of a merchant steamer that passed through Puerto Rico informed the authorities that the troops that garrisoned the fort of Monte Cristi lacked food and fresh meat, encountering many hardships and needs.

According to Bosch, “the gigantic, heroic collective effort and military exploits waged by the men and women who participated in it are unknown.” The incursion of the people into the revolutionary scenario is highly significant, since it allowed the development of a “language of resistance” and “solidarity” in the Caribbean.

Most of these individual advantages disappear from the moment they form part of a large body: without discipline, without instruction, without trust in their leaders, whose ignorance in the matters of war they are unaware of, they cannot be considered troops for regular combat (... ).

Many times, hidden in the mountains under the trunk of a fallen tree or sheltered in its thick branches, they see a column marching ten paces away that they do not even suspect of its existence, and the reckless straggler who separates himself twenty from the last gathered force, "He is a sure victim of his machete.

Many Spanish soldiers lost their left hands under the spirited onslaught of our encroachments.Recently, Historian José Miguel Soto Jiménez announced the public launch of his book The Motifs of the Machete.

In some way, that means that in Santo Domingo, the machete defeated the sword, the pike and the halberd, silenced the harquebus, the musket and the carronade, prevailed over the saber, the pistol and the rifle, humiliating and jugulating the sharp pride of the bayonet and mowing down the hoarse voice of the field guns.

As an abolitionist and revolutionary, (and key organizer of the Grito de Lares), he was said to be a tenacious opponent of the annexationist presidents Buenaventura Baez and Silvain Salnave in the Dominican Republic and Haiti, respectively.

Its agreement with the broad lines of Marti's revolutionary strategy: not expect anything from Spain, from its late reforms and petty, do not try to find another solution that does not be independence; achieve it through a inescapable, popular and rapid liberating war; join all patriots, without discrimination of class or race; distrust North American politics, openly expansionist; prepare together with independence, the conditions of the future democratic Republic.After returning to the Dominican Republic, his contributions began with the solidarity work that developed from Mayaguez, (Puerto Rico) when the Restoration War broke out on August 16, 1863.

Our cry for independence will be heard and supported by the friends of freedom; and there will be no shortage of weapons and money to sink into the dust to the despots of Cuba, Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo.

The documents established the role played by Betances and Francisco Basora in defense of the reestablishment of sovereignty and Dominican independence, since the first was named agent of the Provisional Restorative Government.

The first document was a letter from General Meliton Valverde to the Secretary of Foreign Affairs, dated July 16, 1864, in which Betances and his lieutenant, Francisco Basora, were appointed agents of the Restoration War, the first in Paris and London and the second in New York.

For the book of Carlos Rama, it is known that Basra was known as "The Santo Domingo agent, who participated together to Juan Manuel Macias in the Democratic Society of Friends of America, whose objective was to help the Dominican people in their fight against Spain".