Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, CBE FRS (/ˈpaɪ.ərlz/; German: [ˈpaɪɐls]; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allied nuclear bomb programme.

In 1932, he was awarded a Rockefeller Fellowship, which he used to study in Rome under Enrico Fermi, and then at the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge under Ralph H. Fowler.

Because of his Jewish background, he elected to not return home after Adolf Hitler's rise to power in 1933, but to remain in Britain, where he worked with Hans Bethe at the Victoria University of Manchester, then at the Mond Laboratory at Cambridge.

In 1937, Mark Oliphant, the newly appointed Australian professor of physics at the University of Birmingham recruited him for a new chair there in applied mathematics.

[8] In 1926 Peierls decided to transfer to the University of Munich to study under Arnold Sommerfeld, who was considered to be the greatest teacher of theoretical physics.

[13] Heisenberg left in 1929 to lecture in America, China, Japan and India,[13] and on his recommendation Peierls moved on to ETH Zurich, where he studied under Wolfgang Pauli.

[15] His theory made specific predictions of the behaviour of metals at very low temperatures, but another twenty years would pass before the techniques were developed to confirm them experimentally.

His early work on quantum physics led to the theory of positive carriers to explain the thermal and electrical conductivity behaviours of semiconductors.

[30] In 1936, Mark Oliphant was appointed the professor of physics at the University of Birmingham, and he approached Peierls about a new chair in applied mathematics that he was creating there.

[32] With Kapur he derived the dispersion formula for nuclear reactions originally given in perturbation theory by Gregory Breit and Eugene Wigner, but now included generalising conditions.

The Second World War broke out before it could be published; but drafts were circulated for comment, and it became one of the most cited unpublished papers of all time.

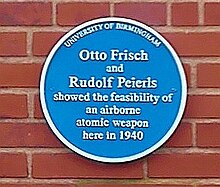

[34] After the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, Peierls started working on nuclear weapons research with Otto Robert Frisch, a fellow refugee from Germany.

The true figure for the critical mass is about four times as large; but until then it had been assumed that such a bomb would require many tons of uranium, and consequently was impractical to build and use.

In 1941 its findings made their way to the United States through the report of the MAUD Committee, an important trigger in the establishment of the Manhattan Project and the subsequent development of the atomic bomb.

With the Frisch-Peierls memorandum and the MAUD Committee report, the British and American scientists were able to begin thinking about how to create a bomb, not whether it was possible.

[41] As enemy aliens, Frisch and Peierls were initially excluded from the MAUD Committee, but the absurdity of this was soon recognised, and they were made members of its Technical Subcommittee.

[44] As a result of the MAUD Committee's findings, a new directorate known as Tube Alloys was created to coordinate the nuclear weapons development effort.

Sir John Anderson, the Lord President of the Council, became the minister responsible, and Wallace Akers from Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was appointed the director of Tube Alloys.

[46] Later that year, Peierls flew to the United States, where he visited Urey and Fermi in New York, Arthur H. Compton in Chicago, Robert Oppenheimer in Berkeley, and Jesse Beams in Charlottesville, Virginia.

[47] When George Kistiakowsky argued that a nuclear weapon would do little damage as most of the energy would be expended heating the air, Peierls, Fuchs, Geoffrey Taylor and J. G. Kynch worked out the hydrodynamics to refute this.

[49] Akers had already cabled London with instructions that Chadwick, Peierls, Oliphant and Simon should leave immediately for North America to join the British Mission to the Manhattan Project, and they arrived the day the agreement was signed.

[50] Simon and Peierls were attached to the Kellex Corporation, which was engaged in the K-25 Project, designing and building the American gaseous diffusion plant.

[51] While Kellex was located in the Woolworth Building, Peierls, Simon and Nicholas Kurti had their offices in the British supply mission on Wall Street.

Oppenheimer then wrote to the director of the Manhattan Project, Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, Jr, requesting that Peierls be sent to take Teller's place in T Division.

[62] For his services to the nuclear weapons project, he was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1946 New Year Honours,[63] and was awarded the US Medal of Freedom with Silver Palm in 1946.

[68] In 2009, Vogel/Pers was outed as being actually Russell A. McNutt, a civil engineer employed by the company Kellex to work on facilities at Oak Ridge, who was recruited as a spy by Julius Rosenberg.

[70] Peierls had a Russian wife, as did his brother, and he maintained close contact with colleagues in the Soviet Union before and after the Second World War.

A similar request the following year was granted,[74] but in 1957 the Americans expressed concerns about him, indicating that they were unwilling to share information with the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell while he remained as a consultant.

[1] Peierls had largely left solid state physics behind when, in 1953, he began collecting his lecture notes on the subject into a book.

These included Gerald E. Brown, Max Krook, Tony Skyrme, Dick Dalitz, Freeman Dyson, Luigi Arialdo Radicati di Brozolo, Stuart Butler, Walter Marshal, Stanley Mandelstam and Elliott H.