James Watson

[10] Watson, Crick and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material".

From 1968, Watson served as director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), greatly expanding its level of funding and research.

In 2019, following the broadcast of a documentary in which Watson reiterated these views on race and genetics, CSHL revoked his honorary titles and severed all ties with him.

[18] In his autobiography, Avoid Boring People, Watson described the University of Chicago as an "idyllic academic institution where he was instilled with the capacity for critical thought and an ethical compulsion not to suffer fools who impeded his search for truth", in contrast to his description of later experiences.

Luria eventually shared the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the Luria–Delbrück experiment, which concerned the nature of genetic mutations.

[27] The other major molecular component of chromosomes, DNA, was widely considered to be a "stupid tetranucleotide", serving only a structural role to support the proteins.

[28] Even at this early time, Watson, under the influence of the Phage Group, was aware of the Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment, which suggested that DNA was the genetic molecule.

[30] After working part of the year with Kalckar, Watson spent the remainder of his time in Copenhagen conducting experiments with microbial physiologist Ole Maaløe, then a member of the Phage Group.

[37][38] Sir Lawrence Bragg,[39] the director of the Cavendish Laboratory (where Watson and Crick worked), made the original announcement of the discovery at a Solvay conference on proteins in Belgium on April 8, 1953; it went unreported by the press.

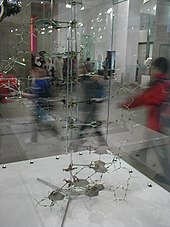

Sydney Brenner, Jack Dunitz, Dorothy Hodgkin, Leslie Orgel, and Beryl M. Oughton were some of the first people in April 1953 to see the model of the structure of DNA, constructed by Crick and Watson; at the time, they were working at Oxford University's chemistry department.

[37] The publication of the double helix structure of DNA has been described as a turning point in science; understanding of life was fundamentally changed and the modern era of biology began.

[44] Watson and Crick's use of DNA X-ray diffraction data collected by Rosalind Franklin and her student Raymond Gosling has attracted scrutiny.

In recent years, Watson has garnered controversy in the popular and scientific press for his "misogynist treatment" of Franklin and his failure to properly attribute her work on DNA.

[38] According to one critic, Watson's portrayal of Franklin in The Double Helix was negative, giving the impression that she was Wilkins' assistant and was unable to interpret her own DNA data.

[23] From a 2003 piece by Brenda Maddox in Nature:[38] Other comments dismissive of "Rosy" in Watson's book caught the attention of the emerging women's movement in the late 1960s.

[46] Matthew Cobb and Nathaniel C. Comfort write that "Franklin was no victim in how the DNA double helix was solved" but that she was "an equal contributor to the solution of the structure".

Franklin's letters were framed with the normal and unremarkable forms of address, beginning with "Dear Jim", and concluding with "Best Wishes, Yours, Rosalind".

[60] The book details the story of the discovery of the structure of DNA, as well as the personalities, conflicts and controversy surrounding their work, and includes many of his private emotional impressions at the time.

In his roles as director, president, and chancellor, Watson led CSHL to articulate its present-day mission, "dedication to exploring molecular biology and genetics in order to advance the understanding and ability to diagnose and treat cancers, neurological diseases, and other causes of human suffering.

Watson was quoted in The Sunday Telegraph in 1997 as stating: "If you could find the gene which determines sexuality and a woman decides she doesn't want a homosexual child, well, let her.

Watson intended to contribute the proceeds to conservation work in Long Island and to funding research at Trinity College, Dublin.

[88] Several of Watson's former doctoral students subsequently became notable in their own right including, Mario Capecchi,[3] Bob Horvitz, Peter B. Moore and Joan Steitz.

[95] In his 2007 memoir, Avoid Boring People: Lessons from a Life in Science, Watson describes his academic colleagues as "dinosaurs", "deadbeats", "fossils", "has-beens", "mediocre", and "vapid".

E. O. Wilson once described Watson as "the most unpleasant human being I had ever met", but in a later TV interview said that he considered them friends and their rivalry at Harvard "old history" (when they had competed for funding in their respective fields).

[97][98] In the epilogue to the memoir Avoid Boring People, Watson alternately attacks and defends former Harvard University president Lawrence Summers, who stepped down in 2006 due in part to his remarks about women and science.

[99] Watson also states in the epilogue, "Anyone sincerely interested in understanding the imbalance in the representation of men and women in science must reasonably be prepared at least to consider the extent to which nature may figure, even with the clear evidence that nurture is strongly implicated.

"[74][96] At a conference in 2000, Watson suggested a link between skin color and sex drive, hypothesizing that dark-skinned people have stronger libidos.

[111][112][113][114] An editorial in Nature said that his remarks were "beyond the pale" but expressed a wish that the tour had not been canceled so that Watson would have had to face his critics in person, encouraging scientific discussion on the matter.

[125] In January 2019, following the broadcast of a television documentary made the previous year in which he repeated his views about race and genetics, CSHL revoked honorary titles that it had awarded to Watson and cut all remaining ties with him.

Watson sometimes talks about his son Rufus, who has schizophrenia, seeking to encourage progress in the understanding and treatment of mental illness by determining how genetics contributes to it.