Dowding system

The Dowding system[a] was the world's first wide-area ground-controlled interception network,[2] controlling the airspace across the United Kingdom from northern Scotland to the southern coast of England.

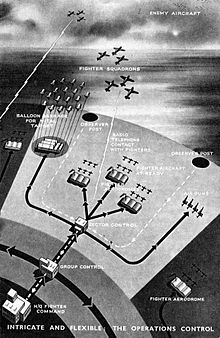

It used a widespread dedicated land-line telephone network to rapidly collect information from Chain Home (CH) radar stations and the Royal Observer Corps (ROC) in order to build a single image of the entire UK airspace and then direct defensive interceptor aircraft and anti-aircraft artillery against enemy targets.

The system was built by the Royal Air Force just before the start of World War II, and proved decisive in the Battle of Britain.

[8] Experiments with acoustic mirrors and similar devices were carried out but these always proved unsatisfactory, with detection ranges often as low as 5 miles (8.0 km) even in good conditions.

[12] On 27 July, Henry Tizard suggested running a series of experiments of fighter interception, based on an estimated fifteen-minute warning time that RDF would provide.

[14][d] Tizard introduced the equal angles method of rapidly estimating an interception point, by imagining the fighters and bombers at the opposite corners on the base of an isosceles triangle.

On one occasion, Dowding was watching the displays of the test system for any sign of the attackers when he heard them pass overhead, a complete failure.

Dowding, Tizard, and mathematician Patrick Blackett, another founding member of the committee, began evolving a new system that inherited concepts from ADGB.

[19] By early 1939, the basic system had been built out, and from 11 August 1939, Bomber Command was asked to launch a series of mock attacks using aircraft returning from exercises over France.

Small wooden blocks with tags were placed on the map to represent the location of various formations, indicated by the track number created in the filter room.

Dowding, Blackett and Tizard personally drove home the fact that the pilots could not simply hunt for their targets, and had to follow the instructions of the operations centres.

For instance, the filter room might be receiving 15 reports per minute from various CH sites, but these would be about formations that might cover the entire coast of Great Britain.

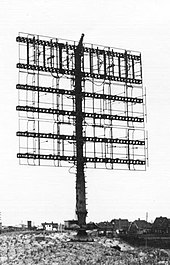

[26] Chain Home offered an enormous improvement in early detection times compared to older systems of visual or acoustic location.

For this task, operations rooms also contained a series of blackboards and electrical lamp systems indicating the force strengths of the fighter squadrons and their current status.

It was the responsibility of the Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) plotters[h] to continually update the tote and weather boards, and relay that information up the chain.

[21] Observing the map from above, group commanders could track the movements of enemy aircraft through their patch, examine the tote board, select a squadron and called their sector to have them scramble.

Vectoring was accomplished using the methods developed in the Biggin Hill exercises in 1935, with the sector commander comparing the location of the friendly aircraft with the hostile plots being transferred from group and arranging the interception.

[29] Thus, an update on an enemy's position might take the form "Tennis leader this is Sapper control, your customers are now over Maidstone, vector zero-nine-zero, angels two-zero".

Communications were ensured by hundreds of miles of dedicated phone lines laid by the GPO and buried deep underground to prevent them from being cut by bombs.

With the only detection means being the observers and acoustic location with ranges on the order of 20 miles (32 km) under the very best conditions, the bombers would be over their targets before the spotters could call in the raid and the fighters could climb to their altitude.

A 16 July 1940 Luftwaffe intelligence report failed to even mention it, in spite of being aware of it through signals intercepts and having complete details of its World War I predecessor.

A later report on 7 August did make mention of the system, but only to suggest that it would tie fighters to their sectors, reducing their flexibility and ability to deal with large raids.

[36] While discussing the events with British historians immediately after the war, Erhard Milch and Adolf Galland both expressed their belief that one or two CH stations might have been destroyed during early raids, but they proved difficult targets.

But the historians interviewing them noted, "neither seemed to realize how important were the RDF stations to Fighter Command technique of interception or how embarrassing sustained attacks upon them would have been.

Most critics wanted the filter room to be moved from Bentley Priory to Group commands, lowering the reporting volume at each location and providing duplication.

The set was low power, with a range of about 40 miles (64 kilometres) air-to-ground and 5 mi (8.0 km) air-to-air,[j] which presented numerous problems with reception quality.

[39] Chain Home could only produce information of aircraft in "front" of the antennas, typically off-shore, and the reporting system relied on the OC once the raid was over land.

During the battle, Leigh-Mallory repeatedly failed to send his fighters to cover 11 Group airfields, preferring instead to build his "Big Wing" formations to attack the Luftwaffe.

He was then summoned to the Air Staff on 1 October and was forced to implement this change, although he delayed this until all fighters were equipped with new IFF Mark II systems.

The explosion of the Soviet atomic bomb in 1949 and the presence of Tupolev Tu-4 "Bull" aircraft that could deliver it to the UK led to the rapid construction of the ROTOR system.