Drakensberg

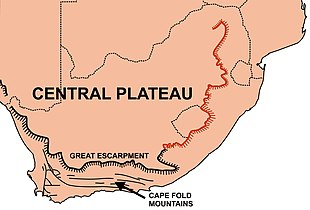

The Great Escarpment reaches its greatest elevation – 2,000 to 3,482 metres (6,562 to 11,424 feet) within the border region of South Africa and Lesotho.

The escarpment winds north from there, through Mpumalanga, where it includes features such as the Blyde River Canyon, Three Rondavels, and God's Window.

The absence of the Great Escarpment for approximately 450 km (280 mi) to the north of Tzaneen (to reappear on the border between Zimbabwe and Mozambique in the Chimanimani Mountains) is due to a failed westerly branch of the main rift that caused Antarctica to start drifting away from southern Africa during the breakup of Gondwana about 150 million years ago.

[5] During the past 20 million years, southern Africa has experienced massive uplifting, especially in the east, with the result that most of the plateau lies above 1,000 m (3,300 ft) despite extensive erosion.

It reaches its highest point of over 3,000 m (9,800 ft) where the escarpment forms part of the international border between Lesotho and the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal.

The Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and Lesotho Drakensberg have hard erosion-resistant upper surfaces and therefore have a very rugged appearance, combining steep-sided blocks and pinnacles (giving rise to the Zulu name "Barrier of up-pointed spears").

The "Lesotho Mountains" are formed away from the Drakensberg escarpment by erosion gulleys which turn into deep valleys containing tributaries of the Orange River.

Previously, angular debris was presumed to have been created by changes typical of cold, periglacial environments, such as fracturing due to frost.

The Limpopo and Mpumalanga Drakensberg are capped by an erosion resistant quartzite layer that is part of the Transvaal Supergroup, which also forms the Magaliesberg to the north and northwest of Pretoria.

South of the 26°S parallel the Drakensberg escarpment is composed of Ecca shales, which belong to the Karoo Supergroup, and they are 300 million years old.

[5][8] That layer rests on the youngest of the Karoo Supergroup sediments, the Clarens sandstone, which was laid down under desert conditions, about 200 million years ago.

The rivers that run from the Drakensberg are an essential resource for South Africa's economy, providing water for the industrial provinces of Mpumalanga and Gauteng, which contains the city of Johannesburg.

[10] The flora of the high alti-montane grasslands is mainly tussock grass, creeping plants, and small shrubs such as ericas.

In the highest part of Drakensberg the composition of the flora is independent on slope aspect (direction) and varies, depending on the hardness of the rock clasts.

[11] One bird is endemic to the high peaks, the mountain pipit (Anthus hoeschi), and another six species are found mainly here: Bush blackcap (Lioptilus nigricapillus), buff-streaked chat (Oenanthe bifasciata), Rudd's lark (Heteromirafra ruddi), Drakensberg rockjumper (Chaetops aurantius), yellow-breasted pipit (Anthus chloris), and Drakensberg siskin (Serinus symonsi).

[12][13] The lower slopes of the Drakensberg support much wildlife, perhaps most importantly the rare southern white rhinoceros (which was nurtured here when facing extinction) and the black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnou, which as of 2011[update] only thrives in protected areas and game reserves).

Adjacent to the Ukhahlamba Drakensberg World Heritage Site is the 1900 ha Allendale Mountain Reserve, which is the largest private reserve adjoining the World Heritage Site and is found in the accessible Kamberg area, the heart of the historic San (Bushman) painting region of the Ukhahlamba.

Nearly all of the original grassland and forest has disappeared and more protection is needed, although the Giant's Castle reserve is a haven for the eland and also is a breeding ground for the bearded vulture.

Some 20,000 individual rock paintings have been recorded at 500 different caves and overhanging sites between the Drakensberg Royal Natal National Park and Bushman's Nek.