Dream

Dream interpretation, practiced by the Babylonians in the third millennium BCE[4] and even earlier by the ancient Sumerians,[5][6] figures prominently in religious texts in several traditions, and has played a lead role in psychotherapy.

[10][11] Long ago, according to writings from Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, dreams dictated post-dream behaviors to an extent that was sharply reduced in later millennia.

[17] Preserved writings from early Mediterranean civilizations indicate a relatively abrupt change in subjective dream experience between Bronze Age antiquity and the beginnings of the classical era.

[19][10][20] Gudea, the king of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash (reigned c. 2144–2124 BCE), rebuilt the temple of Ningirsu as the result of a dream in which he was told to do so.

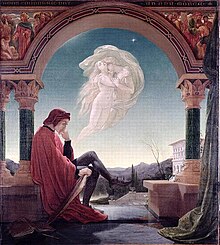

[6] After antiquity, the passive hearing of visitation dreams essentially gave way to visualized narratives in which the dreamer becomes a character who actively participates.

The visuals (including locations, people, and objects) are generally reflective of a person's memories and experiences, but conversation can take on highly exaggerated and bizarre forms.

This analysis revealed that themes involving fear, illness, and death were two to four times more prevalent in dreams following the onset of the pandemic than they were before.

[29] Non-invasive measures of brain activity like electroencephalogram (EEG) voltage averaging or cerebral blood flow cannot identify small but influential neuronal populations.

Following their work with split-brain subjects, Gazzaniga and LeDoux postulated, without attempting to specify the neural mechanisms, a "left-brain interpreter" that seeks to create a plausible narrative from whatever electro-chemical signals reach the brain's left hemisphere.

[35] Drawing on this knowledge, textbook author James W. Kalat explains, "[A] dream represents the brain's effort to make sense of sparse and distorted information....

"[36] Neuroscientist Indre Viskontas is even more blunt, calling often bizarre dream content "just the result of your interpreter trying to create a story out of random neural signaling.

"[37] For many humans across multiple eras and cultures, dreams are believed to have functioned as revealers of truths sourced during sleep from gods or other external entities.

[14] From a Darwinian perspective dreams would have to fulfill some kind of biological requirement, provide some benefit for natural selection to take place, or at least have no negative impact on fitness.

[46] Crick's and Mitchison's 1983 "reverse learning" theory, which states that dreams are like the cleaning-up operations of computers when they are offline, removing (suppressing) parasitic nodes and other "junk" from the mind during sleep.

[47][48] Hartmann's 1995 proposal that dreams serve a "quasi-therapeutic" function, enabling the dreamer to process trauma in a safe place.

[52] Erik Hoel proposes, based on artificial neural networks, that dreams prevent overfitting to past experiences; that is, they enable the dreamer to learn from novel situations.

J. W. Dunne wrote: But there can be no reasonable doubt that the idea of a soul must have first arisen in the mind of primitive man as a result of observation of his dreams.

The famous glossary, the Somniale Danielis, written in the name of Daniel, attempted to teach Christian populations to interpret their dreams.

The earliest Greek beliefs about dreams were that their gods physically visited the dreamers, where they entered through a keyhole, exiting the same way after the divine message was given.

[72] Greek philosopher Plato (427–347 BCE) wrote that people harbor secret, repressed desires, such as incest, murder, adultery, and conquest, which build up during the day and run rampant during the night in dreams.

[73] Plato's student, Aristotle (384–322 BCE), believed dreams were caused by processing incomplete physiological activity during sleep, such as eyes trying to see while the sleeper's eyelids were closed.

Dreamworlds, shared hallucinations and other alternate realities feature in a number of works by Philip K. Dick, such as The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch and Ubik.

[92] Dreams may be psychically invaded or manipulated (Dreamscape, 1984; the Nightmare on Elm Street films, 1984–2010; Inception, 2010) or even come literally true (as in The Lathe of Heaven, 1971).

On April 12, 1975, after agreeing to move his eyes left and right upon becoming lucid, the subject and Hearne's co-author on the resulting article, Alan Worsley, successfully carried out this task.

The processes involved included EEG monitoring, ocular signaling, incorporation of reality in the form of red light stimuli and a coordinating website.

[112][113] A daydream is a visionary fantasy, especially one of happy, pleasant thoughts, hopes or ambitions, imagined as coming to pass, and experienced while awake.

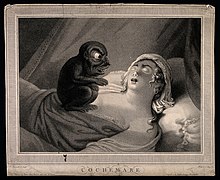

A nightmare is an unpleasant dream that can cause a strong negative emotional response from the mind, typically fear or horror, but also despair, anxiety and great sadness.

[120] Melatonin is a natural hormone secreted by the brain's pineal gland, inducing nocturnal behaviors in animals and sleep in humans during nighttime.

Chemically isolated in 1958, melatonin has been marketed as a sleep aid since the 1990s and is currently sold in the United States as an over-the-counter product requiring no prescription.

Anecdotal reports and formal research studies over the past few decades have established a link between melatonin supplementation and more vivid dreams.