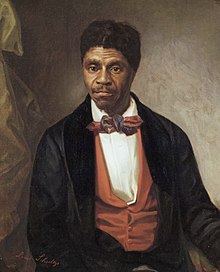

Dred Scott v. Sandford

[7] The decision involved the case of Dred Scott, an enslaved black man whose owners had taken him from Missouri, a slave-holding state, into Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, where slavery was illegal.

When his owners later brought him back to Missouri, Scott sued for his freedom and claimed that because he had been taken into "free" U.S. territory, he had automatically been freed and was legally no longer a slave.

In an opinion written by Chief Justice Roger Taney, the Court ruled that people of African descent "are not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word 'citizens' in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges which that instrument provides for and secures to citizens of the United States"; more specifically, that African Americans were not entitled to "full liberty of speech ... to hold public meetings ... and to keep and carry arms" along with other constitutionally protected rights and privileges.

[8] Taney supported his ruling with an extended survey of American state and local laws from the time of the Constitution's drafting in 1787 that purported to show that a "perpetual and impassable barrier was intended to be erected between the white race and the one which they had reduced to slavery."

[2] After ruling on those issues surrounding Scott, Taney struck down the Missouri Compromise because, by prohibiting slavery in U.S. territories north of the 36°30′ parallel, it interfered with slave owners' property rights under the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

[10][11][12] The ruling is widely considered a blatant act of judicial activism[13] with the intent of bringing finality to the territorial crisis resulting from the Louisiana Purchase by creating a constitutional right to own slaves anywhere in the country while permanently disenfranchising all people of African descent.

One scholar suggests that, in all likelihood, the Scotts would have been granted their freedom by a Louisiana court, as it had respected laws of free states that slaveholders forfeited their right to slaves if they brought them in for extended periods.

[23]: 41 In Rachel v. Walker, the state supreme court had ruled that a U.S. Army officer who took a slave to a military post in a territory where slavery was prohibited and retained her there for several years, had thereby "forfeit[ed] his property".

[20] Scott's new lawyers, Alexander P. Field and David N. Hall, argued that the writ of error was inappropriate because the lower court had not yet issued a final judgment.

[29][23]: 55 On February 13, 1850, Emerson's defense filed a bill of exceptions, which was certified by Judge Hamilton, setting into motion another appeal to the Missouri Supreme Court.

[23] Counsel for the opposing sides signed an agreement that moving forward, only Dred Scott v. Irene Emerson would be advanced, and that any decision made by the high court would apply to Harriet's suit, also.

[28]: 135 The reorganized Missouri Supreme Court now included two moderates – Hamilton Gamble and John Ryland – and one staunch proslavery justice, William Scott.

[31][23]: 63 According to historian Walter Ehrlich, the closing of Norris's brief was "a racist harangue that not only revealed the prejudices of its author, but also indicated how the Dred Scott case had become a vehicle for the expression of such views".

[23]: 63 Noting that Norris's proslavery "doctrines" were later incorporated into the court's final decision,[23]: 62 Ehrlich writes (emphasis his):From this point on, the Dred Scott case clearly changed from a genuine freedom suit to the controversial political issue for which it became infamous in American history.

Since then not only individuals but States have been possessed with a dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery, whose gratification is sought in the pursuit of measures, whose inevitable consequence must be the overthrow and destruction of our government.

[33] After the Missouri Supreme Court decision, Judge Hamilton turned down a request by Emerson's lawyers to release the rent payments from escrow and to deliver the slaves into their owner's custody.

He later successfully pressured Associate Justice Robert Cooper Grier, a Northerner, to join the Southern majority in Dred Scott to prevent the appearance that the decision was made along sectional lines.

[17] The question is simply this: Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States, and as such become entitled to all of the rights, and privileges, and immunities, guarantied [sic] by that instrument to the citizen?In answer, the Court ruled they could not.

On the contrary, they were at that time [of America's founding] considered as a subordinate and inferior class of beings who had been subjugated by the dominant race, and, whether emancipated or not, yet remained subject to their authority, and had no rights or privileges but such as those who held the power and the Government might choose to grant them.The Court then extensively reviewed laws from the original American states that involved the status of black Americans at the time of the Constitution's drafting in 1787.

They had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order ... and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.This holding normally would have ended the decision, since it disposed of Dred Scott's case by effectively declaring that Scott had no standing to bring suit, but Taney did not confine his ruling to the matter immediately before the Court.

Upon these considerations, it is the opinion of the court that the act of Congress which prohibited a citizen from holding and owning property of this kind in the territory of the United States north of the [36°N 30' latitude] line therein mentioned is not warranted by the Constitution, and is therefore void....Taney held that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional, marking the first time since the 1803 case Marbury v. Madison that the Supreme Court had struck down a federal law, although the Missouri Compromise had already been effectively overridden by the Kansas–Nebraska Act.

"[40] The American political historian Robert G. McCloskey described: The tempest of malediction that burst over the judges seems to have stunned them; far from extinguishing the slavery controversy, they had fanned its flames and had, moreover, deeply endangered the security of the judicial arm of government.

Southern Democrats considered Republicans to be lawless rebels who were provoking disunion by their refusal to accept the Supreme Court's decision as the law of the land.

Stephen Douglas attacked that position in the Lincoln-Douglas debates:Mr. Lincoln goes for a warfare upon the Supreme Court of the United States, because of their judicial decision in the Dred Scott case.

Senator from Mississippi and later President of the Confederacy, the case merely "presented the question whether Cuffee [a derogatory term for a black person] should be kept in his normal condition or not .

[20] Economist Charles Calomiris and historian Larry Schweikart discovered that uncertainty about whether the entire West would suddenly become slave territory or engulfed in guerilla conflict like "Bleeding Kansas" gripped the markets immediately.

The east-west railroads became insolvent immediately (although north-south lines were unaffected), in turn causing dangerous runs on several large banks, events known as the Panic of 1857.

In 1860, the Republican Party explicitly rejected the Dred Scott verdict in their official platform, stating "the new dogma that the Constitution, of its own force, carries slavery into any or all of the territories of the United States, is a dangerous political heresy, at variance with the explicit provisions of that instrument itself, with contemporaneous exposition, and with legislative and judicial precedent; is revolutionary in its tendency, and subversive of the peace and harmony of the country.

In 1896, in the Jim Crow era, Justice John Marshall Harlan was the lone dissenting vote in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which declared racial segregation constitutional and created the concept of "separate but equal".

[64] Chief Justice John Roberts compared Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) to Dred Scott as another example of trying to settle a contentious issue through a ruling that went beyond the scope of the Constitution.