Drug metabolism

These reactions often act to detoxify poisonous compounds (although in some cases the intermediates in xenobiotic metabolism can themselves cause toxic effects).

These pathways are also important in environmental science, with the xenobiotic metabolism of microorganisms determining whether a pollutant will be broken down during bioremediation, or persist in the environment.

[citation needed] The exact compounds an organism is exposed to will be largely unpredictable, and may differ widely over time; these are major characteristics of xenobiotic toxic stress.

Polar compounds cannot diffuse across these cell membranes, and the uptake of useful molecules is mediated through transport proteins that specifically select substrates from the extracellular mixture.

However, the existence of a permeability barrier means that organisms were able to evolve detoxification systems that exploit the hydrophobicity common to membrane-permeable xenobiotics.

These enzyme complexes act to incorporate an atom of oxygen into nonactivated hydrocarbons, which can result in either the introduction of hydroxyl groups or N-, O- and S-dealkylation of substrates.

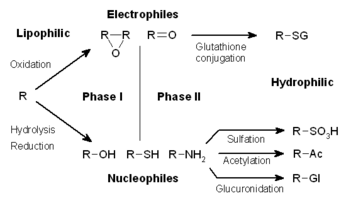

However, many phase I products are not eliminated rapidly and undergo a subsequent reaction in which an endogenous substrate combines with the newly incorporated functional group to form a highly polar conjugate.

As an example, the major metabolite of the pharmaceutical trimebutine, desmethyltrimebutine (nor-trimebutine), can be efficiently produced by in vitro oxidation of the commercially available drug.

During reduction reactions, a chemical can enter futile cycling, in which it gains a free-radical electron, then promptly loses it to oxygen (to form a superoxide anion).

In subsequent phase II reactions, these activated xenobiotic metabolites are conjugated with charged species such as glutathione (GSH), sulfate, glycine, or glucuronic acid.

Sites on drugs where conjugation reactions occur include carboxy (-COOH), hydroxy (-OH), amino (NH2), and thiol (-SH) groups.

The addition of large anionic groups (such as GSH) detoxifies reactive electrophiles and produces more polar metabolites that cannot diffuse across membranes, and may, therefore, be actively transported.

Conjugates and their metabolites can be excreted from cells in phase III of their metabolism, with the anionic groups acting as affinity tags for a variety of membrane transporters of the multidrug resistance protein (MRP) family.

The similarity of these molecules to useful metabolites therefore means that different detoxification enzymes are usually required for the metabolism of each group of endogenous toxins.

If a drug is taken into the GI tract, where it enters hepatic circulation through the portal vein, it becomes well-metabolized and is said to show the first pass effect.

In general, anything that increases the rate of metabolism (e.g., enzyme induction) of a pharmacologically active metabolite will decrease the duration and intensity of the drug action.

Physiological factors that can influence drug metabolism include age, individual variation (e.g., pharmacogenetics), enterohepatic circulation, nutrition, sex differences or gut microbiota.

[medical citation needed] Pathological factors can also influence drug metabolism, including liver, kidney, or heart diseases.

[medical citation needed] In silico modelling and simulation methods allow drug metabolism to be predicted in virtual patient populations prior to performing clinical studies in human subjects.

Studies on how people transform the substances that they ingest began in the mid-nineteenth century, with chemists discovering that organic chemicals such as benzaldehyde could be oxidized and conjugated to amino acids in the human body.

[21] This modern biochemical research resulted in the identification of glutathione S-transferases in 1961,[22] followed by the discovery of cytochrome P450s in 1962,[23] and the realization of their central role in xenobiotic metabolism in 1963.