Kingdom of East Anglia

Rædwald, the first East Anglian king to be baptised a Christian, is seen by many scholars to be the person buried within (or commemorated by) the ship burial at Sutton Hoo, near Woodbridge.

Several of Rædwald's successors were killed in battle, such as Sigeberht, under whose rule and with the guidance of his bishop, Felix of Burgundy, Christianity was firmly established.

In 903 the exiled Æthelwold ætheling induced the East Anglian Danes to wage a disastrous war on his cousin Edward the Elder.

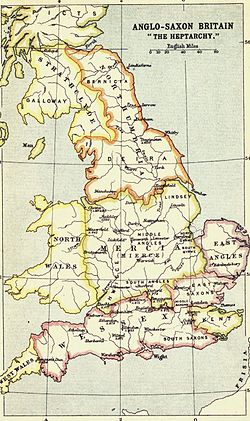

[2] It emerged from the political consolidation of the Angles in the approximate area of the former territory of the Iceni and the Roman civitas, with its centre at Venta Icenorum, close to Caistor St Edmund.

[6] While the archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that a large-scale migration and settlement of the region by continental Germanic speakers occurred,[7] it has been questioned whether all of the migrants self-identified as Angles.

[12] Nothing is known of the earliest kings, or how the kingdom was organised, although a possible centre of royal power is the concentration of ship-burials at Snape and Sutton Hoo in eastern Suffolk.

[16] It has been suggested by Blair, on the strength of parallels between some objects found under Mound 1 at Sutton Hoo and those discovered at Vendel in Sweden, that the Wuffingas may have been descendants of an eastern Swedish royal family.

[18] From 616, when pagan monarchs briefly returned in Kent and Essex, East Anglia until Rædwald's death was the only Anglo-Saxon kingdom with a reigning baptised king.

Beornwulf of Mercia's attempt to restore Mercian control resulted in his defeat and death, and his successor Ludeca met the same end in 827.

[30] In 865, East Anglia was invaded by the Danish Great Heathen Army, which occupied winter quarters and secured horses before departing for Northumbria.

[31] The Danes returned in 869 to winter at Thetford, before being attacked by the forces of Edmund of East Anglia, who was defeated and killed at Hægelisdun[b] and then buried at Beodericsworth.

In 880 the Vikings returned to East Anglia under Guthrum, who according to the medieval historian Pauline Stafford, "swiftly adapted to territorial kingship and its trappings, including the minting of coins.

"[35] Along with the traditional territory of East Anglia, Cambridgeshire and parts of Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire, Guthrum's kingdom probably included Essex, the one portion of Wessex to come under Danish control.

In 901, Edward's cousin Æthelwold ætheling,[c] having been driven into exile after an unsuccessful bid for the throne, arrived in Essex after a stay in Northumbria.

A rapid succession of defeats culminated in the loss of the territories of Northampton and Huntingdon, along with the rest of Essex: a Danish king, probably from East Anglia, was killed at Tempsford.

Despite reinforcement from overseas, the Danish counter-attacks were crushed, and after the defection of many of their English subjects as Edward's army advanced, the Danes of East Anglia and of Cambridge capitulated.

Their language is historically important, as they were among the first Germanic settlers to arrive in Britain during the 5th century: according to Kortmann and Schneider, East Anglia "can seriously claim to be the first place in the world where English was spoken.

"[44] As no East Anglian manuscripts, Old English inscriptions or literary records such as charters have survived, there is little evidence to support the existence of such a dialect.

According to a study by Von Feilitzen in the 1930s, the recording of many place-names in Domesday Book was "ultimately based on the evidence of local juries" and so the spoken form of Anglo-Saxon places and people was partly preserved in this way.

[45] Evidence from Domesday Book and later sources suggests that a dialect boundary once existed, corresponding with a line that separates from their neighbours the English counties of Cambridgeshire (including the once sparsely-inhabited Fens), Norfolk and Suffolk.

[47] Erosion on the eastern border and deposition on the north coast altered the East Anglian coastline in Roman and Anglo-Saxon times (and continues to do so).