Echmarcach mac Ragnaill

A leading member of this kindred, Donnchad mac Briain, King of Munster, was married to Cacht ingen Ragnaill, a woman who could have been closely related to Echmarcach.

Echmarcach's violent career brought him into bitter conflict with a particular branch of the Uí Ímair who had held Dublin periodically from the early eleventh century.

This branch was supported by the rising Uí Cheinnselaig, an Irish kindred responsible for Echmarcach's final expulsion from Dublin and apparently Mann as well.

[19] Echmarcach appears to first emerge in the historical record in the first half of the eleventh century, when he was one of the three kings who met with Knútr Sveinnsson,[21] ruler of the Anglo-Scandinavian Empire comprising the kingdoms of Denmark, England, and Norway.

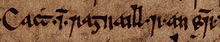

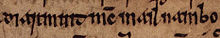

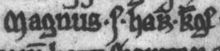

The later "E" version provides more information, stating that, after his return from Rome in 1031, Knútr went to Scotland and received the submission of three kings named: "Mælcolm", "Mælbæþe", and "Iehmarc".

[38] If Rodulfus' account is to be believed, this conflict must have taken place before Richard's death in 1026, and could refer to events surrounding Máel Coluim's violent annexation of Lothian early in Knútr's reign.

[43] As for Máel Coluim, his influence in the Isles may be evidenced by the twelfth-century Prophecy of Berchán, which could indicate that he resided or exerted power in the Hebrides, specifically on the Inner Hebridean islands of Arran and Islay.

[48] One possibility is that the account of Máel Coluim preserved by the Prophecy of Berchán could be evidence that this region encompassed the lands surrounding Kintyre and the Outer Clyde.

[54] There appears to be evidence that the violent regime change in Moray (which enabled Mac Bethad to assume the mormaership) prompted Knútr to meet with the kings.

[55] Another possibility is that Máel Coluim aimed to gain Knútr's neutrality in a Scottish campaign against Mac Bethad, and sought naval support from Echmarcach himself.

[79] For example, the thirteenth-century Orkneyinga saga states that, after Þórfinnr's consolidation of Orkney and Caithness—an action that likely took place after the death of his brother Brúsi—Þórfinnr was active in the Isles, parts of Galloway and Scotland, and even Dublin.

[80] The saga also reveals that Brúsi's son, Rǫgnvaldr, arrived in Orkney at a time when Þórfinnr was preoccupied with the after-effects of such campaigns, as it states that he was "much occupied" with men from the Isles and Ireland.

[81] Another source, Óláfs saga helga, preserved within the thirteenth-century saga-compilation Heimskringla, claims that Þórfinnr exerted power in Scotland and Ireland, and that he controlled a far-flung lordship which encompassed Orkney, Shetland, and the Hebrides.

If this was the case, Hákon would have been responsible for not only a strategic part of the Anglo-Welsh frontier, but also accountable for the far-reaching sea-lanes that stretched from the Irish Sea region to Norway.

[11] Having come to terms with the three kings, it is possible that Knútr relied upon Echmarcach to counter the ambitions of the Orcadians, who could have attempted to seize upon Hákon's fall and renew their influence in the Isles.

[93] Following his meeting with Knútr, Echmarcach appears to have allied himself with the Uí Briain,[95] the descendants of Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig, High King of Ireland.

[11] According to a poetic verse composed by the contemporary Icelandic skald Óttarr svarti, Knútr's subjects included Danes, Englishmen, Irishmen, and Islesmen.

This could mean that Echmarcach's expulsion of Sitriuc was a direct act of vengeance for the latter's slaying of Ragnall ua Ímair (then King of Waterford) the year before.

[144] Ímar appears have been a descendant (possibly a grandson) of Amlaíb Cuarán, and thus a close relative of the latter's son, Sitriuc, whom Echmarcach drove from the kingship only two years before.

[146] The fact that Ímar proceeded to campaign in the North Channel could indicate that Echmarcach had held power in this region before his acquisition of Mann and Dublin.

[153] In fact, the wealth and sophistication of commerce in Echmarcach's realm could in part explain why the constant struggle for control of Dublin and the Isles was so bitter, and could account for Þórfinnr's apparent presence in the region.

Specifically, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Brut y Tywysogyon, and the twelfth-century Chronicon ex chronicis record that a Norse-Gaelic fleet sailed up the River Usk, and ravaged the surrounding region.

Such unease could partly account for Siward's extension of power into the Solway region, a sphere of insecure territory which may have been regarded as vulnerable by Echmarcach.

[166] These annalistic accounts indicate that, although Diarmait's conquest evidently began with a mere raid upon Fine Gall, this action further escalated into the seizure of Dublin itself.

Following several skirmishes fought around the town's central fortress, the aforesaid accounts report that Echmarcach fled overseas, whereupon Diarmait assumed the kingship.

[168] In consequence of Echmarcach's expulsion, Dublin effectively became the provincial capital of Leinster,[169] with the town's remarkable wealth and military power at Diarmait's disposal.

Ælfgar evidently received considerable military aid from the Irish to form a fleet of eighteen ships, and together with Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, King of Gwynedd and Deheubarth invaded Herefordshire.

[191] Diarmait also appears to have previously backed Cynan ab Iago, a man who was a bitter rival and seemingly the eventual slayer of Ælfgar's ally and son-in-law, Gruffudd ap Llywelyn.

Certainly, the thirteenth- to fourteenth-century Chronicle of Mann records that Ímar's apparent son, Gofraid Crobán—a future ruler of Dublin and the Isles—backed the Norwegian invasion of England led by Magnús' father in 1066.

[226] Earlier in the century, the entire region may have formed part of Sitriuc's realm,[227] and various Irish and Welsh sources indicate that it may have been held by one of the latter's two sons named Amlaíb.