Economy of New Zealand

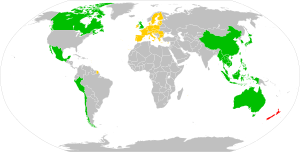

New Zealand has one of the most globalised economies and depends greatly on international trade, mainly with China, Australia, the European Union, the United States, Japan and Korea.

As of February 2023[update], NZX had a total of 338 listed securities, equity, debt and funds with a combined market capitalisation of NZD $226 billion.

[34] In the 1960s, prices for these traditional exports declined, and in 1973 New Zealand lost its preferential trading position with the United Kingdom when the latter joined the European Economic Community.

[39] Prior to European settlement and colonisation of New Zealand, Māori had a subsistence economy, the basic economic unit of which was the sub-tribe or hapū in which labour was divided.

Their crews traded European goods, including guns and metal tools, for Māori food, water, wood, flax and sex.

[44] Progress slowed after the collapse of the City of Glasgow Bank in 1878 which led to a contraction in credit from London, the centre of the world's financial system at the time.

Holyoake's deputy and successor, Jack Marshall, (briefly Prime Minister in 1972) negotiated continued access for New Zealand exports to the United Kingdom under the so-called "Luxembourg Agreement".

The Government of Norman Kirk, who succeeded Marshall, put greater emphasis on expanding New Zealand's trade, especially with South East Asia.

A new range of products for export such as ammonia, urea fertilizer, methanol and petrol were produced and with greater use of electricity (with the electrification of the North Island Main Trunk railway) with the goal that this would reduce New Zealand's dependence on oil imports.

[39] Other projects included the Clyde Dam on the Clutha River, which was built to meet a growing demand for electricity, and the expansion of the New Zealand Steel plant at Glenbrook.

[56] The Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter, which opened in 1971, was also upgraded as part of the Think Big strategy and now brings in approximately NZ$1 billion in exports every year.

Between 1984 and 1993, New Zealand underwent radical economic reform, moving from what had probably been the most protected, regulated and state-dominated system of any capitalist democracy to an extreme position at the open, competitive, free-market end of the spectrum.

The changes included making the Reserve Bank independent of political decisions; performance contracts for senior civil servants; public sector finance reform based on accrual accounting; tax neutrality; subsidy-free agriculture; and industry-neutral competition regulation.

From then on the Reserve Bank focused on keeping inflation low and stable, using the Official Cash Rate (OCR) – the price of borrowing money in New Zealand – as its primary means to do so.

[82][83][84][85][86] In an attempt to stimulate the economy, the Reserve Bank lowered the Official Cash Rate (OCR) from a high of 8.25% (July 2008) to an all-time low of 2.5% at the end of April 2009.

[76] In 2009 the economy picked up, led by strong demand from major trading partners Australia and China, and historically high prices for New Zealand's dairy and log exports.

In 2010 the GDP grew by a modest 1.6%, but over the next couple of years economic activity continued to improve, driven by the rebuild in Canterbury after the Christchurch earthquakes and recovery in domestic demand.

[88] Only three months later, the New Zealand Productivity Commission expressed concern about low living standards and problems affecting the long-term drivers of growth.

[96] After successfully containing the virus, the New Zealand economy had sharp growth in what is known as a V-shaped recovery and ended the year with an overall economic expansion of 0.4%, better than the predicted 1.7% contraction.

[100] By 23 September 2021, the Restaurant Association's Chief executive Marisa Bidois estimated that about 1,000 hospitality businesses nationwide had been forced to close as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to the loss of 13,000 jobs.

According to figures released by Statistics New Zealand, the rising cost of construction, petrol and rents pushed the consumer price index up 1.4 per cent between October and December 2021.

By contrast, the opposition National Party leader Christopher Luxon and Finance spokesperson Simon Bridges attributed rising inflation to the Government's "wasteful" spending.

[103] On 1 February 2022, an annual report released by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) identified the country's border restrictions and declining house prices as the main risks facing New Zealand's economy that year.

[106] In 2015 the Social Progress Index, which covers such areas as basic human needs, foundations of well-being, and the level of opportunity available to citizens, ranked the New Zealand economy fifth in the world.

Approximately 8% of purchases go to overseas-based cash buyers[126] – primarily Australians, Chinese, and British – although most[quantify] economists believe that foreign investment is currently[when?]

"[148] A report prepared for the Association of Consulting and Engineering New Zealand in 2020 claimed that there was an infrastructure deficit of $75 billion (about one quarter of GDP), following decades of under-investment that began in the 1980s.

Australia is now the destination of 19% of New Zealand's exports, including light crude oil, gold, wine, cheese and timber, as well as a wide range of manufactured items.

The CER also creates a free labour market which allows New Zealand and Australian citizens to live and work freely in each other's country together with mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

New Zealand also trades with Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, India and the Philippines and this now accounts for around 16% of total exports.

Goods exported to the islands include refined oil, construction materials, medicines, sheep meat, milk, butter, fruit and vegetables.

Inverted yield curve in 1994–1998 and 2004–2008

|

New Zealand

Free trade agreements in force

Free trade agreements concluded but not in force

|