Geography of Scotland in the Middle Ages

Scotland was defined by its physical geography, with its long coastline of inlets, islands and inland lochs, high proportion of land over 60 metres above sea level and heavy rainfall.

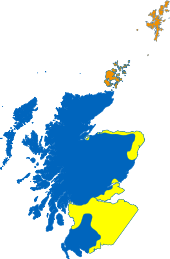

In the middle of this period, through a process of conquest, consolidation and treaty, the boundaries of Scotland were gradually extended from a small area under direct control of the kings of Alba in the east, to almost its modern borders.

For most of the medieval era the monarchy and court was itinerant, with Scone and Dunfermline acting as important centres and later Roxburgh, Stirling and Perth, before Edinburgh emerged as the political capital in the fourteenth century.

Modern Scotland is half the size of England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland lochs, it has roughly the same amount of coastline at 4,000 miles.

The existence of hills, mountains, quicksands and marshes made internal communication and conquest extremely difficult and may have contributed to the fragmented nature of political power.

[2] This was reversed in the period c. 1150 to 1300, with warm dry summers and less severe winters allowing cultivation at much greater heights above sea level and making land more productive.

In the late Middle Ages, average temperatures began to reduce again, with cooler and wetter conditions limiting the extent of arable agriculture, particularly in the Highlands.

[5] The Central Lowland belt averages about 50 miles in width,[6] and because it contains most of the good quality agricultural land and has easier communications, could support most of the urbanisation and elements of conventional medieval government.

[9] But it also made those areas problematic to govern for Scottish kings and much of the political history of the era after the wars of independence centred on attempts to resolve problems of entrenched localism.

[13] In the areas of Scandinavian settlement in the Islands and along the coast a lack of timber meant that native materials had to be adopted for house building, often combining layers of stone with turf.

[15] Early Gaelic settlement appears to have been in the regions of the western mainland of Scotland between Cowal and Ardnamurchan, and the adjacent islands, later extending up the West coast in the eighth century.

[21] Burghs were typically surrounded by a palisade or had a castle and usually a market place, with a widened high street or junction, often marked by a mercat cross beside which were houses for the burgesses and other inhabitants.

[24] The known conditions have been taken to suggest it was a high-fertility, high-mortality society, similar to many developing countries in the modern world, with a relatively young demographic profile, and perhaps early childbearing, and large numbers of children for women.

The result would have been a relatively small proportion of available workers to the number of mouths to feed, making it difficult to produce a surplus that would allow demographic growth and more complex societies to develop.

[27] Compared with the situation after the redistribution of population in the later clearances and the Industrial Revolution, these numbers would have been relatively evenly spread over the kingdom, with roughly half living north of the Tay.

[31] By the High Middle Ages the majority of people within Scotland spoke the Gaelic language, then simply called Scottish, or in Latin, lingua Scotica.

[35] At least from the accession of David I, Gaelic ceased to be the main language of the royal court and was replaced by Norman French, to be followed by the Chancery, the castles of nobles and the upper order of the Church.

[38] The expansion of Alba into the wider kingdom of Scotland was a gradual process combining external conquest and the suppression of occasional rebellions, with the extension of seigniorial power through the placement of effective agents of the crown.

In the ninth century the term mormaer, meaning "great steward", began to appear in the records to describe the rulers of Moray, Strathearn, Buchan, Angus and Mearns, who may have acted as "marcher lords" for the kingdom to counter the Viking threat.

[40] Later the process of consolidation is associated with the feudalism introduced by David I, which, particularly in the east and south where the crown's authority was greatest, saw the placement of lordships, often based on castles, and the creation of administrative sheriffdoms, which overlay the pattern of local thegns.

[44] Iona was an early religious centre, and was said to be the burial place of the kings of Alba until the end of the eleventh century, but declined as a result of Viking raids from 794.