Ecosystem ecology

Studies of ecosystem function have greatly improved human understanding of sustainable production of forage, fiber, fuel, and provision of water.

This example demonstrates several important aspects of ecosystems: These characteristics also introduce practical problems into natural resource management.

An individual ecosystem is composed of populations of organisms, interacting within communities, and contributing to the cycling of nutrients and the flow of energy.

Population, community, and physiological ecology provide many of the underlying biological mechanisms influencing ecosystems and the processes they maintain.

Ecosystem ecology approaches organisms and abiotic pools of energy and nutrients as an integrated system which distinguishes it from associated sciences such as biogeochemistry.

In this model, energy flows through the whole system were dependent on biotic and abiotic interactions of each individual component (species, inorganic pools of nutrients, etc.).

[6] Water provision and filtration, production of biomass in forestry, agriculture, and fisheries, and removal of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere are examples of ecosystem services essential to public health and economic opportunity.

Maximizing production in degraded systems is an overly simplistic solution to the complex problems of hunger and economic security.

[8][9] These strategies risk alteration of ecosystem processes that may be difficult to restore, especially when applied at broad scales without adequate assessment of impacts.

[10][11] An appreciation of the importance of ecosystem function in maintenance of productivity, whether in agriculture or forestry, is needed in conjunction with plans for restoration of essential processes.

Improved knowledge of ecosystem function will help to achieve long-term sustainability and stability in the poorest parts of the world.

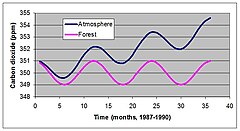

NPP is difficult to measure but a new technique known as eddy co-variance has shed light on how natural ecosystems influence the atmosphere.

[22] Ecosystems dominated by plants with low-lignin concentration often have rapid rates of decomposition and nutrient cycling (Chapin et al. 1982).

[24] In addition to litter quality and climate, the activity of soil fauna is very important [25] However, these models do not reflect simultaneous linear and non-linear decay processes which likely occur during decomposition.

One of the most obvious patterns in Figure 3 is that as one moves up to higher trophic levels (i.e. from plants to top-carnivores) the total amount of energy decreases.

These influences can dramatically shift dominant species in terrestrial and marine systems[28][29] The interplay and relative strength of top-down vs. bottom-up controls on ecosystem structure and function is an important area of research in the greater field of ecology.

Stadler[32] showed that C rich honeydew produced during aphid outbreak can result in increased N immobilization by soil microbes thus slowing down nutrient cycling and potentially limiting biomass production.

[34] Without these functions intact, economic value of ecosystems is greatly reduced and potentially dangerous conditions may develop in the field.

For example, areas within the mountainous western highlands of Guatemala are more susceptible to catastrophic landslides and crippling seasonal water shortages due to loss of forest resources.