Eddington experiment

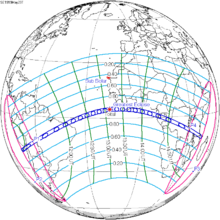

The observations were of the total solar eclipse of 29 May 1919 and were carried out by two expeditions, one to the West African island of Príncipe, and the other to the Brazilian town of Sobral.

Initially, in a paper published in 1911, Einstein had incorrectly calculated that the amount of light deflection was the same as the Newtonian value, that is 0.83 seconds of arc for a star that would be just on the limb of the Sun in the absence of gravity.

In 1912 Freundlich asked if Perrine would include observation of light deflection as part of the Argentine Observatory's program for the solar eclipse of 10 October 1912 in Brazil.

Perrine and the Cordoba team were the only eclipse expedition to construct specialized equipment dedicated to observe light deflection.

[3] Eddington and Perrine spent several days together in Brazil and may have discussed their observation programs including Einstein's prediction of light deflection.

[3][5][6] A second attempt by American astronomers to measure the effect during the 1918 eclipse was foiled by clouds in one location[7] and by ambiguous results due to the lack of the correct equipment in another.

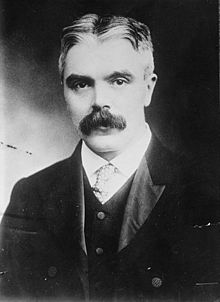

[10] Eddington's interest in general relativity began in 1916, during World War I, when he read papers by Einstein (presented in Berlin, Germany, in 1915), which had been sent by the neutral Dutch physicist Willem de Sitter to the Royal Astronomical Society in Britain.

Eddington, later said to be one of the few people at the time to understand the theory, realised its significance and lectured on relativity at a meeting at the British Association in 1916.

This exemption was later appealed by the War Ministry, and at a series of hearings in June and July 1918, Eddington, who was a Quaker, stated that he was a conscientious objector, based on religious grounds.

[12] At the final hearing, the Astronomer Royal, Frank Watson Dyson, supported the exemption by proposing that Eddington undertake an expedition to observe the total eclipse in May the following year to test Einstein's General Theory of Relativity.

The first observation of light deflection was performed by noting the change in position of stars as they passed near the Sun on the celestial sphere.

Dyson, when planning the expedition in 1916, had chosen the 1919 eclipse because it would take place with the Sun in front of a bright group of stars called the Hyades.

Two teams of two people were to be sent to make observations of the eclipse at two locations: the West African island of Príncipe and the Brazilian town of Sobral.

In mid-1918, researchers from the Brazilian National Observatory, determined that the city of Sobral, Ceará, was the best geographical position to observe the Solar Eclipse.

Its director, Henrique Charles Morize [pt], sent a report to worldwide scientific institutions on the subject, including the Royal Astronomical Society, London.

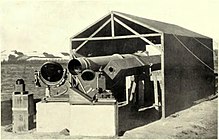

The equipment used for the expedition to Príncipe, an island in the Gulf of Guinea off the coast of West Africa, was an astrographic lens borrowed from the Radcliffe Observatory in Oxford.

[2] Following the return of the expedition, Eddington was addressing a dinner held by the Royal Astronomical Society, and, showing his more light-hearted side, recited the following verse that he had composed in a style parodying the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam:[20] Oh leave the Wise our measures to collate One thing at least is certain, light has weight One thing is certain and the rest debate Light rays, when near the Sun, do not go straight.

[8] On 12 April 1923, William Wallace Campbell announced that the preliminary new results confirmed Einstein's theory of relativity and prediction of the amount of light deflection with measurements from over 200 stars.

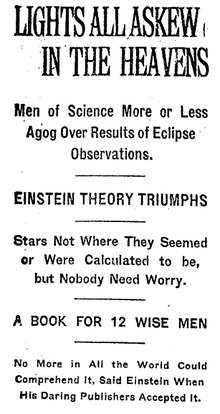

While Einstein had been a moderately famous public figure in Germany for a few years by that time, the articles in question marked the beginning of his international celebrity status.

[32] It is notable that while the Eddington results were seen as a confirmation of Einstein's prediction, and in that capacity soon found their way into general relativity text books,[33] among other astronomers there followed a decade-long discussion of the quantitative values of light deflection, with the precise results in contention even after several expeditions had repeated Eddington's observations on the occasion of subsequent eclipses.

[37] Those measurements and their successors are nowadays an important part of the so-called post-Newtonian tests of gravity, the systematic way of parametrizing the predictions of general relativity and other theories in terms of ten adjustable parameters in the context of the parameterized post-Newtonian formalism, where each parameter represents a possible departure from Newton's law of universal gravitation.

[38] Similar concerns about systematic errors and possibly confirmation bias were raised in the science history community[39] and gained more prominence as part of the popular book The Golem by Trevor Pinch and Harry Collins.

[40] A modern reanalysis of the dataset, though, suggests that Eddington's analysis was accurate, and in fact less afflicted by bias than some of the analyses of solar eclipse data that followed.

[41][42] Part of the vindication comes from a 1979 reanalysis of the plates from the two Sobral instruments, using a much more modern plate-measuring machine than was available in 1919, which supports Eddington's results.