Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

By the 1880s, the book was extremely popular throughout the English-speaking world, to the extent that numerous "Omar Khayyam clubs" were formed and there was a "fin de siècle cult of the Rubaiyat".

[1] FitzGerald's work has been published in several hundred editions and has inspired similar translation efforts in English, Hindi and in many other languages.

[4]: 11 The extant manuscripts containing collections attributed to Omar are dated much too late to enable a reconstruction of a body of authentic verses.

In the 1930s, Iranian scholars, notably Mohammad-Ali Foroughi, attempted to reconstruct a core of authentic verses from scattered quotes by authors of the 13th and 14th centuries, ignoring the younger manuscript tradition.

De Blois (2004) is pessimistic, suggesting that contemporary scholarship has not advanced beyond the situation of the 1930s, when Hans Heinrich Schaeder commented that the name of Omar Khayyam "is to be struck out from the history of Persian literature".

Sadegh Hedayat commented that "if a man had lived for a hundred years and had changed his religion, philosophy, and beliefs twice a day, he could scarcely have given expression to such a range of ideas".

These include figures such as Shams Tabrizi, Najm al-Din Daya, Al-Ghazali, and Attar, who "viewed Khayyam not as a fellow-mystic, but a free-thinking scientist".

[12] Critics of FitzGerald, on the other hand, have accused the translator of misrepresenting the mysticism of Sufi poetry by an overly literal interpretation.

[13] Dougan (1991) likewise says that attributing hedonism to Omar is due to the failings of FitzGerald's translation, arguing that the poetry is to be understood as "deeply esoteric".

[16] Henry Beveridge states that "the Sufis have unaccountably pressed this writer [Khayyam] into their service; they explain away some of his blasphemies by forced interpretations, and others they represent as innocent freedoms and reproaches".

[18] He concludes that "religion has proved incapable of surmounting his inherent fears; thus Khayyam finds himself alone and insecure in a universe about which his knowledge is nil".

[20] Notable editions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries include: Houghton, Mifflin & Co. (1887, 1888, 1894); Doxey, At the Sign of the Lark (1898, 1900), illustrations by Florence Lundborg; The Macmillan Company (1899); Methuen (1900) with a commentary by H.M. Batson, and a biographical introduction by E.D.

[24] To a large extent, the Rubaiyat can be considered original poetry by FitzGerald loosely based on Omar's quatrains rather than a "translation" in the narrow sense.

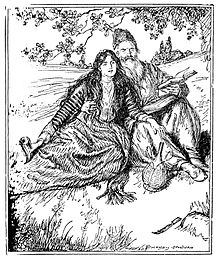

(letter to E. B. Cowell, 4/27/59)For comparison, here are two versions of the same quatrain by FitzGerald, from the 1859 and 1889 editions: Herewith a Loaf of Bread beneath the Bough, A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse—and Thou Beside me singing in the Wilderness— And Wilderness is Paradise enow.

A Book of Verses underneath the Bough, A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread—and Thou Beside me singing in the Wilderness— Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!

In the literal prose translation of Edward Heron-Allen (1898):[26] I desire a little ruby wine and a book of verses, Just enough to keep me alive, and half a loaf is needful; And then, that I and thou should sit in a desolate place Is better than the kingdom of a sultan.

If a loaf of wheaten-bread be forthcoming, a gourd of wine, and a thigh-bone of mutton, and then, if thou and I be sitting in the wilderness, — that would be a joy to which no sultan can set bounds.

Whinfield's translation is, if possible, even more free than FitzGerald's;[dubious – discuss] Quatrain 84 (equivalent of FitzGerald's quatrain XI in his 1st edition, as above) reads: In the sweet spring a grassy bank I sought And thither wine and a fair Houri brought; And, though the people called me graceless dog, Gave not to Paradise another thought!

20 (equivalent of FitzGerald's quatrain XI in his 1st edition, as above): Yes, Loved One, when the Laughing Spring is blowing, With Thee beside me and the Cup o’erflowing, I pass the day upon this Waving Meadow, And dream the while, no thought on Heaven bestowing.

For instance, he invents a verse in which Khayyam is made to say "the unbeliever knows his Koran best," and rewrites another to describe pious hypocrites as "a maggot-minded, starved, fanatic crew," rather than the original Persian which emphasizes their ignorance of religion.

The English novelist and orientalist Jessie Cadell (1844–1884) consulted various manuscripts of the Rubaiyat with the intention of producing an authoritative edition.

The authors claimed it was based on a twelfth-century manuscript located in Afghanistan, where it was allegedly utilized as a Sufi teaching document.

But the manuscript was never produced, and British experts in Persian literature were easily able to prove that the translation was in fact based on Edward Heron Allen's analysis of possible sources for FitzGerald's work.

A gourd of red wine and a sheaf of poems — A bare subsistence, half a loaf, not more — Supplied us two alone in the free desert: What Sultan could we envy on his throne?

I need a jug of wine and a book of poetry, Half a loaf for a bite to eat, Then you and I, seated in a deserted spot, Will have more wealth than a Sultan's realm.

If chance supplied a loaf of white bread, Two casks of wine and a leg of mutton, In the corner of a garden with a tulip-cheeked girl, There'd be enjoyment no Sultan could outdo.

His focus was to faithfully convey, with less poetic license, Khayyam's original religious, mystical, and historic Persian themes, through the verses as well as his extensive annotations.

Quatrain 151 (equivalent of FitzGerald's quatrain XI in his 1st edition, as above): Gönnt mir, mit dem Liebchen im Gartenrund Zu weilen bei süßem Rebengetränke, Und nennt mich schlimmer als einen Hund, Wenn ferner an's Paradies ich denke!

He did not accept them and after performing the pilgrimage returned to his native land, kept his secrets to himself and propagated worshipping and following the people of faith."

cited after Aminrazavi (2007)[page needed]"The writings of Omar Khayyam are good specimens of Sufism, but are not valued in the West as they ought to be, and the mass of English-speaking people know him only through the poems of Edward Fitzgerald.